שלאָף מײַן קינד, שלאָף כסדר [1]

זינגען װעל איך דיר אַ ליד.

אַז דו, מײַן קינד, װעסט עלטער װערן

וועסטו װיסן אַן אונטערשיד.

אַז דו, מײַן קינד, װעסט עלטער װערן

וועסטו װיסן אַן אונטערשיד.

אַז דו, מײַן קינד, װעסט עלטער װערן

װעסטו װערן מיט מענטשן גלײַך.

דעמאָלסט װעסטו געווויר װערן

װאָס הייסט אָרעם און װאָס הייסט רײַך.

דעמאָלסט װעסטו געווויר װערן

װאָס הייסט אָרעם און װאָס הייסט רײַך.

שלאָף מײַן קינד, שלאָף כסדר

זינגען װעל איך דיר אַ ליד.

אַז דו, מײַן קינד, װעסט עלטער װערן

וועסטו װיסן אַן אונטערשיד.

אַז דו, מײַן קינד, װעסט עלטער װערן

וועסטו װיסן אַן אונטערשיד.

די טײַערסטע פּאַלאַצֿן, די שענסטע הײַזער,

דאָס אַלץ מאַכט דער אָרעמאַן.

נאָר װייסטו װער עס טוט אין זי װױנען?

גאָר ניט ער, נאָר דער רײַכער מאַן.

דער אָרעמאַן, ער לינט אין קעלער,

דער װילנאַטש רינט אים פון די װענט.

דערפון באַקומט ער רעמאַטן-פעלער

אין די פּיס און אין די הענט.

זינגען װעל איך דיר אַ ליד.

אַז דו, מײַן קינד, װעסט עלטער װערן

וועסטו װיסן אַן אונטערשיד.

אַז דו, מײַן קינד, װעסט עלטער װערן

וועסטו װיסן אַן אונטערשיד.

אַז דו, מײַן קינד, װעסט עלטער װערן

װעסטו װערן מיט מענטשן גלײַך.

דעמאָלסט װעסטו געווויר װערן

װאָס הייסט אָרעם און װאָס הייסט רײַך.

דעמאָלסט װעסטו געווויר װערן

װאָס הייסט אָרעם און װאָס הייסט רײַך.

שלאָף מײַן קינד, שלאָף כסדר

זינגען װעל איך דיר אַ ליד.

אַז דו, מײַן קינד, װעסט עלטער װערן

וועסטו װיסן אַן אונטערשיד.

אַז דו, מײַן קינד, װעסט עלטער װערן

וועסטו װיסן אַן אונטערשיד.

די טײַערסטע פּאַלאַצֿן, די שענסטע הײַזער,

דאָס אַלץ מאַכט דער אָרעמאַן.

נאָר װייסטו װער עס טוט אין זי װױנען?

גאָר ניט ער, נאָר דער רײַכער מאַן.

דער אָרעמאַן, ער לינט אין קעלער,

דער װילנאַטש רינט אים פון די װענט.

דערפון באַקומט ער רעמאַטן-פעלער

אין די פּיס און אין די הענט.

[1] טראַנסקריפּציע / Trascrizione / Transcription

Shlof mayn kind, shlof keseyder,

Zingen vel ich dir a lid.

Az du mayn kind vest elter vern

Vestu visn an untershid.

Az du mayn kind vest elter vern

Vestu visn an untershid

Az du mayn kind vest elter vern

Vestu vern mit laytn glaykh.

Damolst vestu gevoyre vern

Vos heyst orem un vos heyst raykh.

Damolst vestu gevoyre vern

Vos heyst orem un vos heyst raykh.

Shlof mayn kind, shlof keseyder,

Zingen vel ich dir a lid.

Az du mayn kind vest elter vern

Vestu visn an untershid.

Az du mayn kind vest elter vern

Vestu visn an untershid

Di tayerste palatsn, di tayerste hayzer

Dos alts makht der oreman

Nor, veystu, ver es tut in zey voynen?

Gornisht der, nor der raykher man

Der oreman, er ligt in keler

Der vilgotsh rint um fun di vent

Derfun bakumt er a rematn-feler

In di fis un in di hent.

Shlof mayn kind, shlof keseyder,

Zingen vel ich dir a lid.

Az du mayn kind vest elter vern

Vestu visn an untershid.

Az du mayn kind vest elter vern

Vestu visn an untershid

Az du mayn kind vest elter vern

Vestu vern mit laytn glaykh.

Damolst vestu gevoyre vern

Vos heyst orem un vos heyst raykh.

Damolst vestu gevoyre vern

Vos heyst orem un vos heyst raykh.

Shlof mayn kind, shlof keseyder,

Zingen vel ich dir a lid.

Az du mayn kind vest elter vern

Vestu visn an untershid.

Az du mayn kind vest elter vern

Vestu visn an untershid

Di tayerste palatsn, di tayerste hayzer

Dos alts makht der oreman

Nor, veystu, ver es tut in zey voynen?

Gornisht der, nor der raykher man

Der oreman, er ligt in keler

Der vilgotsh rint um fun di vent

Derfun bakumt er a rematn-feler

In di fis un in di hent.

Contributed by Riccardo Gullotta - 2021/1/29 - 20:22

Language: English

English translation #1 / ענגליש איבערזעצונג / Traduzione inglese / Traduction anglaise / الترجمة الانكليزية / Englanninkielinen käännös:

Gus Tyler

Gus Tyler

SLEEP MY CHILD, KEEP SLEEPING

Sleep my child, just keep on sleeping

I will sing you for you a song

When you, my child are some years older

You’ll know what’s right and know what’s wrong.

When you, my child, are some years older

When you grow up you’ll know for sure

That not all folk are really equal

For some are rich and some are poor.

The greatest palace, finest homes

Are built by people who are poor.

But who resides beneath their domes?

Some wealthy, lazy, snooty boor!

The man who’s poor lives in a cellar

The water dripping from the wall

He ends up one rheumatic fella

All he can do is crawl and bawl.

Sleep my child, just keep on sleeping

I will sing you for you a song

When you, my child are some years older

You’ll know what’s right and know what’s wrong.

When you, my child, are some years older

When you grow up you’ll know for sure

That not all folk are really equal

For some are rich and some are poor.

The greatest palace, finest homes

Are built by people who are poor.

But who resides beneath their domes?

Some wealthy, lazy, snooty boor!

The man who’s poor lives in a cellar

The water dripping from the wall

He ends up one rheumatic fella

All he can do is crawl and bawl.

Contributed by Riccardo Gullotta - 2021/1/29 - 22:56

Language: English

English translation #2 / ענגליש איבערזעצונג / Traduzione inglese / Traduction anglaise / الترجمة الانكليزية / Englanninkielinen käännös:

Hershl Hartman

Hershl Hartman

SLEEP MY CHILD, SLEEPING PEACEFULLY

Sleep, my child, sleep peacefully,

I'll sing you a lullaby.

When my little baby's grown,

You'll know the difference--and why.

When my little baby's grown

You'll soon see which is which:

Like the rest of us, you'll know

The difference between poor and rich.

The largest mansions, the finest homes,

The poor man builds them on the hill.

But do you know who'll live in them?

Why, of course, the rich man will!

The poor man lives in a cellar:

The walls are wet with damp

That bring pain to his arms and legs

And a rheumatic cramp.

Sleep, my child, sleep peacefully,

I'll sing you a lullaby.

When my little baby's grown,

You'll know the difference--and why.

When my little baby's grown

You'll soon see which is which:

Like the rest of us, you'll know

The difference between poor and rich.

The largest mansions, the finest homes,

The poor man builds them on the hill.

But do you know who'll live in them?

Why, of course, the rich man will!

The poor man lives in a cellar:

The walls are wet with damp

That bring pain to his arms and legs

And a rheumatic cramp.

Contributed by Riccardo Gullotta - 2021/1/29 - 22:57

Language: Italian

Traduzione italiana / Italian translation / Traduction italienne / Italiankielinen käännös:

Riccardo Venturi, 30-1-2021 08:42

A fronte delle versioni metriche in inglese, ecco qui, invece, la traduzione strettamente letterale della canzone con alcune note. Ne ho approfittato anche per rimettere un po' a posto la trascrizione. [RV]

Riccardo Venturi, 30-1-2021 08:42

A fronte delle versioni metriche in inglese, ecco qui, invece, la traduzione strettamente letterale della canzone con alcune note. Ne ho approfittato anche per rimettere un po' a posto la trascrizione. [RV]

Dormi, bambino mio, continua a dormire

Dormi bambino mio, continua a dormire, [1]

Ti voglio cantare una canzone.

Quando, bambino mio, sarai più grande,

Capirai una differenza. [2]

Quando, bambino mio, sarai più grande,

Capirai una differenza.

Quando, bambino mio, sarai più grande

Sarai uguale alla gente.

Allora ti renderai conto

Che vuol dire povero [3] e che vuol dire ricco.

Allora ti renderai conto

Che vuol dire povero e che vuol dire ricco.

Dormi bambino mio, continua a dormire,

Ti voglio cantare una canzone.

Quando, bambino mio, sarai più grande,

Capirai una differenza.

Quando, bambino mio, sarai più grande,

Capirai una differenza.

I palazzi più costosi, le case più costose,

Tutto ciò lo costruisce il povero. [4]

Solo, che lo sai chi ci abita? [5]

Lui no di certo [6], soltanto il ricco.

Il povero, lui, sta in un sotterraneo [7]

L'umidità sgocciola dalle pareti

E quindi si becca i reumatismi

Ai piedi e alle mani.

Dormi bambino mio, continua a dormire, [1]

Ti voglio cantare una canzone.

Quando, bambino mio, sarai più grande,

Capirai una differenza. [2]

Quando, bambino mio, sarai più grande,

Capirai una differenza.

Quando, bambino mio, sarai più grande

Sarai uguale alla gente.

Allora ti renderai conto

Che vuol dire povero [3] e che vuol dire ricco.

Allora ti renderai conto

Che vuol dire povero e che vuol dire ricco.

Dormi bambino mio, continua a dormire,

Ti voglio cantare una canzone.

Quando, bambino mio, sarai più grande,

Capirai una differenza.

Quando, bambino mio, sarai più grande,

Capirai una differenza.

I palazzi più costosi, le case più costose,

Tutto ciò lo costruisce il povero. [4]

Solo, che lo sai chi ci abita? [5]

Lui no di certo [6], soltanto il ricco.

Il povero, lui, sta in un sotterraneo [7]

L'umidità sgocciola dalle pareti

E quindi si becca i reumatismi

Ai piedi e alle mani.

[1] keseyder [כסדר] è, propriamente, il fondamentale sostantivo ebraico סדר [sèder] “ordine, ciclo”, che indica, tra le altre cose, il pranzo rituale pasquale composto da elementi rituali fissi presentati in un dato ordine (il seder di Pesakh). Qui è munito della particella preposizionale ebraica ke- “come”; ma l'espressione ha valore avverbiale nel senso di “continuamente” (si noti anche che, in ebraico moderno, l'espressione בסדר [besèder, bsèder] “in ordine” corrisponde in tutto e per tutto a “ok”).

[2] Visn è, propriamente, “sapere” (ted. wissen).

[3] Lo yiddish orem “povero” corrisponde al tedesco arm, ma ne preserva una forma dialettale medievale, con rispondenze nell'alto tedesco medio. E' un caso frequente nello yiddish, che da dialetti altotedeschi medi ha preso origine.

[4] “Costruisce” ce lo ho messo io, ma lo yiddish qui dice semplicemente “fa” (makht).

[5] Da buon dialetto medievale tedesco, lo yiddish preserva la comunissima costruzione verbale con tun e l'infinito del verbo principale (tut voynen). Interi dialetti tedeschi moderni la hanno conservata, e non è certo raro sentirla anche nel tedesco standard popolare (e persino nella lingua letteraria). Propriamente ha valore rafforzativo (come la corrispondente costruzione inglese: does live), ma in pratica è un'alternativa libera alla normale coniugazione verbale.

[6] Cioè il povero. L'avverbio gornisht in yiddish si scrive sempre in una sola parola, ma è il tedesco gar nicht.

[7] O “in una cantina”. Come nel tedesco Keller, nell'inglese cellar e in tutte le altre lingue germaniche, si tratta di un antichissimo prestito dal latino cellarium.

[2] Visn è, propriamente, “sapere” (ted. wissen).

[3] Lo yiddish orem “povero” corrisponde al tedesco arm, ma ne preserva una forma dialettale medievale, con rispondenze nell'alto tedesco medio. E' un caso frequente nello yiddish, che da dialetti altotedeschi medi ha preso origine.

[4] “Costruisce” ce lo ho messo io, ma lo yiddish qui dice semplicemente “fa” (makht).

[5] Da buon dialetto medievale tedesco, lo yiddish preserva la comunissima costruzione verbale con tun e l'infinito del verbo principale (tut voynen). Interi dialetti tedeschi moderni la hanno conservata, e non è certo raro sentirla anche nel tedesco standard popolare (e persino nella lingua letteraria). Propriamente ha valore rafforzativo (come la corrispondente costruzione inglese: does live), ma in pratica è un'alternativa libera alla normale coniugazione verbale.

[6] Cioè il povero. L'avverbio gornisht in yiddish si scrive sempre in una sola parola, ma è il tedesco gar nicht.

[7] O “in una cantina”. Come nel tedesco Keller, nell'inglese cellar e in tutte le altre lingue germaniche, si tratta di un antichissimo prestito dal latino cellarium.

×

![]()

Note for non-Italian users: Sorry, though the interface of this website is translated into English, most commentaries and biographies are in Italian and/or in other languages like French, German, Spanish, Russian etc.

[ XIX sec ? ]

ליריקס און מוזיק / Testo e musica / Lyrics and music / Paroles et musique / النص والموسيقى / Sanat ja sävel:

אַנאָנימע /Anonimo / Anonymous / Anonyme / مجهول / Nimeämätön

פּערפאָרמער / Interpreti / Performed by / Interprétée par / مطرب / Laulavat :

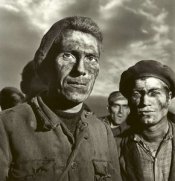

1. Paul Robeson

אלבאם / Album /الألبوم : Shlof, Mein Kind (Sleep, My Child)

2. Tania Solnik

אלבאם / Album /الألبوم :From Generation To Generation: A Legacy Of Lullabies [1993]

La vig lid [ ninna nanna ] Shlof mayn kind, Shlof keseyder fu riscoperta da Ruth Rubin. E’ riportata nel suo libro postumo Yiddish Folksongs from the Ruth Rubin Archive. Nella sua raccolta di 2000 canti yiddish, raccolti con cura per un quarantennio, questa struggente ninnananna fu registrata nel nastro n. 42

Ruth si trovò spesso a partecipare ai concerti folk anche con Paul Robeson.

L’interpretazione di Paul Robeson e la sua figura sono così toccanti da indurci a proporre di classificare la canzone a suo nome, con il permesso di Ruth Rubin e degli Admin.

Nota testuale

L’originale in caratteri ebraici è stato prelevato da questa immagine. Il testo è stato revisionato per renderlo conforme all’audio. Le ultime due strofe non fanno parte delle interpretazioni proposte.

Si riportano due traduzioni inglesi, probabilmente la seconda è quella che rende meglio l’originale. Anche in questa circostanza auspichiamo che Riccardo Venturi assicuri la sua traduzione e qualche nota, per tributare degno omaggio sia alla cultura yiddish sia all’artista e alla persona di Paul Robeson.

[Riccardo Gullotta]