Let me tell a story for I really can't ignore

The happening in Leicestershire in 1984

Two thousand and five hundred walked across that picket line

But a tiny band of miners would not go into the mine

They were called the Dirty Thirty

So they wore that name with pride

As the only striking miners

They stood against the tide

And if you call them heroes

They would surely disagree

But the Dirty Thirty and their kin

are all heroes to me.

The railwaymen at Coalville they backed the miners too

And when a coal train came along They would not let it through

And the women they were mighty maybe mightier than the men

They suffered so much hardship but they'd do it all again

They were called the Dirty Thirty

So they wore that name with pride

As the only striking miners

They stood against the tide

And if you call them heroes

They would surely disagree

But the Dirty Thirty and their kin

are all heroes to me.

So here's to Malcolm Pinnegar – or “Benny” to his friends

Who led the Dirty Thirty Till the strike came to an end

And here's to all the other lads So principled and true

And those who stood beside them Like a worker's mean to do

They were called the Dirty Thirty

So they wore that name with pride

As the only striking miners

They stood against the tide

And if you call them heroes

They would surely disagree

But the Dirty Thirty and their kin

are all heroes to me.

They were called the Dirty Thirty

So they wore that name with pride

As the only striking miners

They stood against the tide

And if you call them heroes

They would surely disagree

But the Dirty Thirty and their kin

are all heroes to me.

Yes, the Dirty Thirty and their kin

are all heroes to me.

The happening in Leicestershire in 1984

Two thousand and five hundred walked across that picket line

But a tiny band of miners would not go into the mine

They were called the Dirty Thirty

So they wore that name with pride

As the only striking miners

They stood against the tide

And if you call them heroes

They would surely disagree

But the Dirty Thirty and their kin

are all heroes to me.

The railwaymen at Coalville they backed the miners too

And when a coal train came along They would not let it through

And the women they were mighty maybe mightier than the men

They suffered so much hardship but they'd do it all again

They were called the Dirty Thirty

So they wore that name with pride

As the only striking miners

They stood against the tide

And if you call them heroes

They would surely disagree

But the Dirty Thirty and their kin

are all heroes to me.

So here's to Malcolm Pinnegar – or “Benny” to his friends

Who led the Dirty Thirty Till the strike came to an end

And here's to all the other lads So principled and true

And those who stood beside them Like a worker's mean to do

They were called the Dirty Thirty

So they wore that name with pride

As the only striking miners

They stood against the tide

And if you call them heroes

They would surely disagree

But the Dirty Thirty and their kin

are all heroes to me.

They were called the Dirty Thirty

So they wore that name with pride

As the only striking miners

They stood against the tide

And if you call them heroes

They would surely disagree

But the Dirty Thirty and their kin

are all heroes to me.

Yes, the Dirty Thirty and their kin

are all heroes to me.

inviata da giorgio - 5/6/2020 - 09:00

×

![]()

Lyrics & music by Alun Parry

Album: When The Sunlight Shines

The miners’ strike of 1984-85 was a major industrial action to shut down the British coal industry in an attempt to prevent colliery closures. It was led by Arthur Scargill of the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) against the National Coal Board (NCB), a government agency. Opposition to the strike was led by the Conservative government of Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, who wanted to reduce the power of the trade unions.

The NUM was divided over the action and many mineworkers, especially in the Midlands, worked through the dispute. Few major trade unions supported the NUM, primarily because of the absence of a vote at national level. Violent confrontations between flying pickets and police characterised the year-long strike, which ended in a decisive victory for the Conservative government and allowed the closure of most of Britain’s collieries. It was “the most bitter industrial dispute in British history”. The number of person-days of work lost to the strike was over 26 million, making it the largest since the 1926 general strike. The journalist Seumas Milne said of the strike, “it has no real parallel – in size, duration and impact – anywhere in the world”.

The NCB was encouraged to gear itself towards reduced subsidies in the early 1980s. After a strike was narrowly averted in February 1981, pit closures and pay restraint led to unofficial strikes. The main strike started on 6 March 1984 with a walkout at Cortonwood Colliery, which led to the NUM’s Yorkshire Area’s sanctioning of a strike on the grounds of a ballot result from 1981 in the Yorkshire Area, which was later challenged in court. The NUM President, Arthur Scargill, made the strike official across Britain on 12 March 1984, but the lack of a national ballot beforehand caused controversy. The NUM strategy was to cause a severe energy shortage of the sort that had won victory in the 1972 strike. The government strategy, designed by Margaret Thatcher, was threefold: to build up ample coal stocks, to keep as many miners at work as possible, and to use police to break up attacks by pickets on working miners. The critical element was the NUM’s failure to hold a national strike ballot.

The strike was ruled illegal in September 1984, as no national ballot of NUM members had been held. It ended on 3 March 1985. It was a defining moment in British industrial relations, the NUM’s defeat significantly weakening the trade union movement. It was a major victory for Thatcher and the Conservative Party, with the Thatcher government able to consolidate their economic programme. The number of strikes fell sharply in 1985 as a result of the “demonstration effect” and trade union power in general diminished. Three deaths resulted from events related to the strike.

The much-reduced coal industry was privatised in December 1994, ultimately becoming UK Coal. In 1983, Britain had 174 working pits, but by 2009 there were only six. Poverty increased in former coal mining areas, and in 1994 Grimethorpe in South Yorkshire was the poorest settlement in the country. (From "Wikipedia")

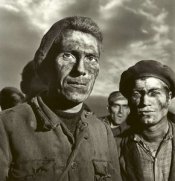

Alun Parry has written a song about the 30 men remained loyal to the NUM who refused to cross the picket line in 1984-85. “The Dirty Thirty” after being inspired by the David Bell’s book about the miners. David Bell from Melton Mowbray published “The Dirty Thirty: Heroes of the Miners Strike” in February 2009 to mark the 25th anniversary of the Miners’ Strike. He interviewed most of the surviving miners and the women's support group. .

These 30 men were the only miners to remain on the picket line while nearly 2,500 of their fellow mineworkers choose to work. David was told by one of the miners: “We don’t see each other every often, but if ever I was in any trouble I’d have 29 people standing by me”. “They were in a struggle together and supported each other”, said David.

“The song reflects the powerful story brilliantly”. Alun said the book “struck a cord” with him. “David lets the people tell the epic story”, said Alun. “It’s a huge thing for any human being to do - to stand up for what they feel is right when they don’t have that support network around them”. The term “Dirty Thirty” has lived on long after the miners’ strike ended in 1985. It was the name given to a small band of Leicestershire NUM members, who joined the year long strike in spite of their right wing branch leaders telling miners in the four pits in the county to work normally. At the time, I was a CPSA (forerunner of the PCS union) branch secretary and I remember being in awe of these brave men, who were prepared to make enormous sacrifices to stand up for what they believed in. Their fight against the Tory government was proved ultimately right. The defeat of the national NUM action, caused in no small part by the leaders of other unions failing to organise supportive strike action by their own members, as well as the ‘scabbing’ activities orchestrated by the right wing in the Leicestershire NUM, led directly to Thatcher’s vengeful destruction of the British mining industry. It also severely dented workers’ confidence in the ability of trade unions to fight for their interests, a legacy which is still felt by significant numbers to this day. Twenty-five years on and David Bell has made good use of the testimony of a number of the Thirty in his book. Bell explains why, against all the odds, they joined the strike and recalls the hardships that they had to endure. It is more of a diary than a political tract. I was a little disappointed by this, especially since Bell quotes one of the main leaders of the Thirty, Malcolm Pinnegar (known as “Benny” - he always wore a woolly hat like the TV Crossroads character), as saying that: “My talks were always very political. The strike was always a political thing to me... ” Bell accepts that he has only mentioned within the book a few of the names of the many supporters of the Thirty throughout the world. But it is a pity that he fails to mention the contribution made by Militant members (forerunner of the Socialist Party). Early in the book, Bell writes that a number of the Thirty came out on strike after the Leicestershire pits were picketed by first the Kent NUM and then miners from South Wales. The first group of these Welsh strikers were from Tower Colliery and were under the leadership of Militant members and their supporters. They had made contact with other Militant members in Leicestershire, who put them up locally and also helped organise the picket that saw Benny, his co-leader Mick Richmond (Richo) and a number of others stick with the dispute for the duration. Some initially thought that they were the only person who had come out on strike and Bell tells the experience of Johnny Gamble, who was actually the sole striker at the South Leicester Colliery. Crucial, therefore, was the solidarity that the Thirty were able to build early on, when a number of them attended a meeting in Coalville in support of the national NUM action. This was organised by the Labour Party Young Socialists under the leadership of Militant.The meeting provided them with a realisation that although they were small in number, Leicestershire had some men who were on strike. Together with many others in the movement, Militant members gave practical support to the Dirty Thirty. We helped organise tours to other areas, attended pickets, raised money and in my own case gave advice about social security benefits that the men or their families could claim. We were an integral part of the network that was crucial both physically and mentally to maintaining the strikers and their magnificent support group of wives, partners and other family members who tirelessly campaigned with them. Bell's book is proof of the struggle and sacrifice of this small group who have subsequently passed into folklore, not just in working class history in Britain but also internationally. He dryly comments that even the official history of the Leicestershire NUM records: “Through their level of activity which was out of all proportion to their numbers, the Dirty Thirty came to have considerable symbolic significance”. A work like this is long overdue and although it is easy to say that it misses this or that out, it captures the events and the spirit of a time that is still very much alive in my own memory. This includes the magnificent support that the Thirty were given by the NUR (now RMT) and Aslef members at the Coalville Mantle Lane depot, many of whom refused to let coal trains move during the dispute. Bell’s text might lack a solid political perspective, but I would still recommend it to anyone who wants to learn about the history of Thatcher’s Britain and its legacy, so warmly embraced by the suits of New Labour.