I’m travellin’ down the Castlereagh, and I’m a station hand,

I’m handy with the ropin’ pole, I’m handy with the brand,

And I can ride a rowdy colt, or swing the axe all day,

But there’s no demand for a station-hand along the Castlereagh.

So it’s shift, boys, shift, for there isn’t the slightest doubt

That we’ve got to make a shift to the stations further out,

With the pack-horse runnin’ after, for he follows like a dog,

We must strike across the country at the old jig-jog.

This old black horse I’m riding—if you’ll notice what’s his brand,

He wears the crooked R, you see—none better in the land.

He takes a lot of beatin’, and the other day we tried,

For a bit of a joke, with a racing bloke, for twenty pounds a side.

It was shift, boys, shift, for there wasn’t the slightest doubt

That I had to make him shift, for the money was nearly out;

But he cantered home a winner, with the other one at the flog—

He’s a red-hot sort to pick up with his old jig-jog.

I asked a cove for shearin’ once along the Marthaguy:

“We shear non-union here,” says he. “I call it scab,” says I.

I looked along the shearin’ floor before I turned to go—

There were eight or ten dashed Chinamen a-shearin’ in a row.

It was shift, boys, shift, for there wasn’t the slightest doubt

It was time to make a shift with the leprosy about.

So I saddled up my horses, and I whistled to my dog,

And I left his scabby station at the old jig-jog.

I went to Illawarra, where my brother’s got a farm,

He has to ask his landlord’s leave before he lifts his arm;

The landlord owns the country side—man, woman, dog, and cat,

They haven’t the cheek to dare to speak without they touch their hat.

It was shift, boys, shift, for there wasn’t the slightest doubt

Their little landlord god and I would soon have fallen out;

Was I to touch my hat to him?—was I his bloomin’ dog?

So I makes for up the country at the old jig-jog.

But it’s time that I was movin’, I’ve a mighty way to go

Till I drink artesian water from a thousand feet below;

Till I meet the overlanders with the cattle comin’ down,

And I’ll work a while till I make a pile, then have a spree in town.

So, it’s shift, boys, shift, for there isn’t the slightest doubt

We’ve got to make a shift to the stations further out;

The pack-horse runs behind us, for he follows like a dog,

And we cross a lot of country at the old jig-jog.

I’m handy with the ropin’ pole, I’m handy with the brand,

And I can ride a rowdy colt, or swing the axe all day,

But there’s no demand for a station-hand along the Castlereagh.

So it’s shift, boys, shift, for there isn’t the slightest doubt

That we’ve got to make a shift to the stations further out,

With the pack-horse runnin’ after, for he follows like a dog,

We must strike across the country at the old jig-jog.

This old black horse I’m riding—if you’ll notice what’s his brand,

He wears the crooked R, you see—none better in the land.

He takes a lot of beatin’, and the other day we tried,

For a bit of a joke, with a racing bloke, for twenty pounds a side.

It was shift, boys, shift, for there wasn’t the slightest doubt

That I had to make him shift, for the money was nearly out;

But he cantered home a winner, with the other one at the flog—

He’s a red-hot sort to pick up with his old jig-jog.

I asked a cove for shearin’ once along the Marthaguy:

“We shear non-union here,” says he. “I call it scab,” says I.

I looked along the shearin’ floor before I turned to go—

There were eight or ten dashed Chinamen a-shearin’ in a row.

It was shift, boys, shift, for there wasn’t the slightest doubt

It was time to make a shift with the leprosy about.

So I saddled up my horses, and I whistled to my dog,

And I left his scabby station at the old jig-jog.

I went to Illawarra, where my brother’s got a farm,

He has to ask his landlord’s leave before he lifts his arm;

The landlord owns the country side—man, woman, dog, and cat,

They haven’t the cheek to dare to speak without they touch their hat.

It was shift, boys, shift, for there wasn’t the slightest doubt

Their little landlord god and I would soon have fallen out;

Was I to touch my hat to him?—was I his bloomin’ dog?

So I makes for up the country at the old jig-jog.

But it’s time that I was movin’, I’ve a mighty way to go

Till I drink artesian water from a thousand feet below;

Till I meet the overlanders with the cattle comin’ down,

And I’ll work a while till I make a pile, then have a spree in town.

So, it’s shift, boys, shift, for there isn’t the slightest doubt

We’ve got to make a shift to the stations further out;

The pack-horse runs behind us, for he follows like a dog,

And we cross a lot of country at the old jig-jog.

envoyé par Bernart Bartleby - 30/11/2017 - 13:54

Sto per contribuire l'originaria "Waltzing Matilda" di Banjo Peterson. Per me è una CCG/AWS bella e buona, avendo pure a che fare con un cruento sciopero dei tosatori di pecore avvenuto da qualche parte in Australia alla fine dell'800...

D'acordo?!? (come diceva la grande Wanna Marchi...)

D'acordo?!? (come diceva la grande Wanna Marchi...)

B.B. - 30/11/2017 - 14:05

This militant unionist ballad was written as a poem by the great Australian bush poet, Banjo Paterson, and published in the Bulletin in 1892 under the name "The Bushman's Song." It has been sung to various tunes, but this one, collected by John Manifold, is the most common.

One of the main targets of union songs is the so-called "scab." A well-known description of a scab, often attributed (probably wrongly) to Jack London, once described scabs as follows: "After God had finished the rattlesnake, the toad, and the vampire, he had some awful substance left with which he made a scab. A scab is a two-legged animal with a corkscrew soul, a water brain, a combination backbone of jelly and glue. Where others have hearts, he carries a tumor of rotten principles. When a scab comes down the street, men turn their backs and Angels weep in Heaven, and the Devil shuts the gates of hell to keep him out ... the modern strikebreaker sells his birthright, his country, his wife, his children, and his fellow men for an unfilled promise from his employer, trust, or corporation."

In fact a lot of the "scabs" who broke the shearers' strikes were Chinese immigrants who came for the gold rush, and subsequently tried to earn a living however they could. In the interests of political correctness, the original line "nine or ten dashed Chinamen" was at some stage changed to "nine or ten non-union men."

I first learnt this song when I was invited by Phil Cleary (well-known Australian footballer, writer and left-wing politician) to sing some songs to his History students. He supplied the songs, some of which I knew already, and I had to learn and sing them as part of a unit on Australian History.

Apparently Ewan MacColl wrote "The Fitter's Song" to the tune of this song, but it must have been one of the other tunes, as it doesn't sound like this one. (Raymond Crooke on Raymond's Folk Song Page)

One of the main targets of union songs is the so-called "scab." A well-known description of a scab, often attributed (probably wrongly) to Jack London, once described scabs as follows: "After God had finished the rattlesnake, the toad, and the vampire, he had some awful substance left with which he made a scab. A scab is a two-legged animal with a corkscrew soul, a water brain, a combination backbone of jelly and glue. Where others have hearts, he carries a tumor of rotten principles. When a scab comes down the street, men turn their backs and Angels weep in Heaven, and the Devil shuts the gates of hell to keep him out ... the modern strikebreaker sells his birthright, his country, his wife, his children, and his fellow men for an unfilled promise from his employer, trust, or corporation."

In fact a lot of the "scabs" who broke the shearers' strikes were Chinese immigrants who came for the gold rush, and subsequently tried to earn a living however they could. In the interests of political correctness, the original line "nine or ten dashed Chinamen" was at some stage changed to "nine or ten non-union men."

I first learnt this song when I was invited by Phil Cleary (well-known Australian footballer, writer and left-wing politician) to sing some songs to his History students. He supplied the songs, some of which I knew already, and I had to learn and sing them as part of a unit on Australian History.

Apparently Ewan MacColl wrote "The Fitter's Song" to the tune of this song, but it must have been one of the other tunes, as it doesn't sound like this one. (Raymond Crooke on Raymond's Folk Song Page)

B.B. - 30/11/2017 - 16:13

×

![]()

“A Bushman's Song” si trova nella raccolta “The Man from Snowy River and Other Verses” pubblicata nel 1895

Trovo questa bush song nel IX° volume nella poderosa raccolta di poesia e musica folk inglese intitolata “Poetry and Song” (14 LP), pubblicata nel 1967.

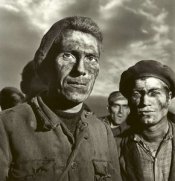

Come in “Waltzing Matilda”, anche qui il protagonista è un bush rider, uno swagman. Nei nostri dizionari il termine viene spesso tradotto con vagabondo, e in effetti lo swagman australiano era spesso una sorta di hobo ma, meglio, un lavoratore girovago che andava di fattoria in fattoria offrendo le proprie braccia.

Ancora oggi la figura dello swagman è in Australia il simbolo di uno spirito anti-autoritario ed indomito.

Infatti qui il nostro protagonista se ne va in cerca di lavoro occasionale, trascinandosi dietro un mulo e un cane, ma non ha molta fortuna: in una fattoria non c’è lavoro, nell’altra danno lavoro solo a non sindacalizzati, crumiri o cinesi sottopagati, in un’altra ancora suo fratello è sfruttato dal landlord peggio di un asino… Non resta che andarsene nel bush, prima o poi arriveranno le grandi mandrie di bestiame da governare e allora lo swagman avrà finalmente quattro soldi per andare a fare baldoria in città...