Wreccan wifes ged [The Wife's Lament; The Wife's Complaint]

anonyme

Langue: anglo-saxon (ca.450-1100)

Ic þis giedd wrece bi me ful geomorre

minre sylfre sið; ic þæt secgan mæg

hwæt ic yrmþa gebad siþþan ic up weox

niwes oþþe ealdes, noma þonne nu

a ic wite wonn minra wræcsiþa!

Ærest min hlaford gewat heonan of leodum

ofer yþa gelac. Hæfde ic uhtceare

hwær min leodfruma londes wære.

Ða icme feran gewat folgað secan,

wineleas wræcca, for minre weaþearfe.

Ongunnon þæt þæs monnes magas hycgan

þurh dyrne geþoht þæt hy todælden unc

þæt wit gewidost in woruldrice

lifdon laðlicost, and mec longade.

Het mec hlaford min her heard niman.

Ahte ic leofra lyt on þissum londstede,

holdra freonda; for þon is min hyge geomor,

ða icme ful gemæcne monnan funde

heardsæligne, hygegeomorne,

mod miþendne, morþor hycgende

bliþe gebæro. Ful oft wit beotedan

þæt unc ne gedælde nemne deað ana.

owiht elles. Eft is þæt onhworfen

is nu […....] swa hit no wære.

freondscipe uncer! Sceal ic feor ge neah

mines fela leofan fæhðu dreogan.

Heht mec mon wunian on wuda bearwe

under actreo in þam eorðscræfe.

Eald is þes eorðsele eal ic eom oflongad;

sindon dena dimme duna uphea,

bitre burgtunas, brerum beweaxne,

wic wynna leas. Ful oft mec her wraþe begeat

fromsiþ frean. Frynd sind on eorþan

leofe lifgende, leger weardiað,

þonne ic on uhtan ana gonge

under actreo geond þas eorðscrafu!

Þær ic sittan mot sumorlangne dæg,

þær ic wepan mæg mine wræcsiþas,

earfoþa fela. For þon ic æfre ne mæg

þære modceare minre gerestan.

Ne ealles þæs longaþes þe mec on þissum life begeat.

A scyle geong mon wesan geomormod,

heard heortan geþoht, swylce habban sceal

bliþe gebæro, eac þon breostceare,

sinsorgna gedreag - sy æt him sylfum gelong

eal his worulde wyn sy ful wide fah

feorres folclondes þæt min freond siteð

under stanhliþe. storme behrimed

wine werigmod, wætre beflowen

on dreorsele. Dreogeð se min wine

micle modceare; he gemon to oft

wynlicran wic. Wa bið þam þe sceal

of langoþe leofes abidan!

minre sylfre sið; ic þæt secgan mæg

hwæt ic yrmþa gebad siþþan ic up weox

niwes oþþe ealdes, noma þonne nu

a ic wite wonn minra wræcsiþa!

Ærest min hlaford gewat heonan of leodum

ofer yþa gelac. Hæfde ic uhtceare

hwær min leodfruma londes wære.

Ða icme feran gewat folgað secan,

wineleas wræcca, for minre weaþearfe.

Ongunnon þæt þæs monnes magas hycgan

þurh dyrne geþoht þæt hy todælden unc

þæt wit gewidost in woruldrice

lifdon laðlicost, and mec longade.

Het mec hlaford min her heard niman.

Ahte ic leofra lyt on þissum londstede,

holdra freonda; for þon is min hyge geomor,

ða icme ful gemæcne monnan funde

heardsæligne, hygegeomorne,

mod miþendne, morþor hycgende

bliþe gebæro. Ful oft wit beotedan

þæt unc ne gedælde nemne deað ana.

owiht elles. Eft is þæt onhworfen

is nu […....] swa hit no wære.

freondscipe uncer! Sceal ic feor ge neah

mines fela leofan fæhðu dreogan.

Heht mec mon wunian on wuda bearwe

under actreo in þam eorðscræfe.

Eald is þes eorðsele eal ic eom oflongad;

sindon dena dimme duna uphea,

bitre burgtunas, brerum beweaxne,

wic wynna leas. Ful oft mec her wraþe begeat

fromsiþ frean. Frynd sind on eorþan

leofe lifgende, leger weardiað,

þonne ic on uhtan ana gonge

under actreo geond þas eorðscrafu!

Þær ic sittan mot sumorlangne dæg,

þær ic wepan mæg mine wræcsiþas,

earfoþa fela. For þon ic æfre ne mæg

þære modceare minre gerestan.

Ne ealles þæs longaþes þe mec on þissum life begeat.

A scyle geong mon wesan geomormod,

heard heortan geþoht, swylce habban sceal

bliþe gebæro, eac þon breostceare,

sinsorgna gedreag - sy æt him sylfum gelong

eal his worulde wyn sy ful wide fah

feorres folclondes þæt min freond siteð

under stanhliþe. storme behrimed

wine werigmod, wætre beflowen

on dreorsele. Dreogeð se min wine

micle modceare; he gemon to oft

wynlicran wic. Wa bið þam þe sceal

of langoþe leofes abidan!

envoyé par Bernart Bartleby - 8/7/2014 - 22:51

Langue: anglo-saxon (ca.450-1100)

Un testo alternativo (con alcune discrepanze testuali rispetto all'edizione di N. Kershaw) ricavato da Wikisource.

Come si può vedere, tale testo osserva la moderna pratica linguistica di segnare la quantità delle vocali lunghe. Si tratta, è bene precisarlo, di un procedimento grafico del tutto contemporaneo e con nessun riscontro nei manoscritti originali. Nel testo che segue viene proposta anche una suddivisione testuale per blocchi, anch'essa del tutto arbitraria. Dal testo è stata rimossa la numerazione dei versi. [RV]

[WRECCAN WIFES GED]

Ic þis giedd wrece bī mē ful gēomorre,

mīnre sylfre sīð. Ic þæt secgan mæg,

hwæt ic yrmþa gebād, siþþan ic ūp āwēox,

nīwes oþþe ealdes, nō mā þonne nū.

Ā ic wite wonn mīnra wræcsīþa.

Ǣrest mīn hlāford gewāt heonan of lēodum

ofer ȳþa gelāc; hæfde ic ūhtceare

hwǣr mīn lēodfruma londes wǣre.

Ðā ic mē fēran gewāt folgað sēcan,

winelēas wræcca, for mīnre wēaþearfe.

Ongunnon þæt þæs monnes māgas hycgan

þurh dyrne geþōht, þæt hȳ tōdǣlden unc,

þæt wit gewīdost in woruldrīce

lifdon lāðlicost, ond mec longade.

Hēt mec hlāford mīn herheard niman,

āhte ic lēofra lȳt on þissum londstede,

holdra frēonda. Forþon is mīn hyge gēomor.

Ðā ic mē ful gemæcne monnan funde,

heardsǣligne, hygegēomorne,

mōd mīþendne, morþor hycgendne

blīþe gebǣro. Ful oft wit bēotedan

þæt unc ne gedǣlde nemne dēað āna

ōwiht elles; eft is þæt onhworfen,

is nū swa hit nǣfre wǣre

frēondscipe uncer. Sceal ic feor ge nēah

mīnes felalēofan fǣhðu drēogan.

Heht mec mon wunian on wuda bearwe,

under āctrēo in þām eorðscræfe.

Eald is þes eorðsele, eal ic eom oflongad,

sindon dena dimme, dūna ūphēa,

bitre burgtūnas, brērum beweaxne,

wīc wynna lēas. Ful oft mec hēr wrāþe begeat

fromsīþ frēan. Frȳnd sind on eorþan,

lēofe lifgende, leger weardiað,

þonne ic on uhtan āna gonge

under āctrēo geond þās eorðscrafu.

Þǣr ic sittan mōt sumorlangne dæg,

þǣr ic wēpan mæg mīne wræcsīþas,

earfoþa fela; forþon ic ǣfre ne mæg

þǣre mōdceare mīnre gerestan,

ne ealles þæs longaþes þe mec on þissum līfe begeat.

Ā scyle geong mon wesan gēomormōd,

heard heortan geþōht, swylce habban sceal

blīþe gebǣro, ēac þon brēostceare,

sinsorgna gedreag. Sȳ æt him sylfum gelong

eal his worulde wyn, sȳ ful wīde fāh

feorres folclondes, þæt mīn frēond siteð

under stānhliþe storme behrīmed,

wine wērigmōd, wætre beflōwen

on drēorsele, drēogeð se mīn wine

micle mōdceare; hē gemon tō oft

wynlicran wīc. Wā bið þām þe sceal

of langoþe lēofes ābīdan.

Ic þis giedd wrece bī mē ful gēomorre,

mīnre sylfre sīð. Ic þæt secgan mæg,

hwæt ic yrmþa gebād, siþþan ic ūp āwēox,

nīwes oþþe ealdes, nō mā þonne nū.

Ā ic wite wonn mīnra wræcsīþa.

Ǣrest mīn hlāford gewāt heonan of lēodum

ofer ȳþa gelāc; hæfde ic ūhtceare

hwǣr mīn lēodfruma londes wǣre.

Ðā ic mē fēran gewāt folgað sēcan,

winelēas wræcca, for mīnre wēaþearfe.

Ongunnon þæt þæs monnes māgas hycgan

þurh dyrne geþōht, þæt hȳ tōdǣlden unc,

þæt wit gewīdost in woruldrīce

lifdon lāðlicost, ond mec longade.

Hēt mec hlāford mīn herheard niman,

āhte ic lēofra lȳt on þissum londstede,

holdra frēonda. Forþon is mīn hyge gēomor.

Ðā ic mē ful gemæcne monnan funde,

heardsǣligne, hygegēomorne,

mōd mīþendne, morþor hycgendne

blīþe gebǣro. Ful oft wit bēotedan

þæt unc ne gedǣlde nemne dēað āna

ōwiht elles; eft is þæt onhworfen,

is nū swa hit nǣfre wǣre

frēondscipe uncer. Sceal ic feor ge nēah

mīnes felalēofan fǣhðu drēogan.

Heht mec mon wunian on wuda bearwe,

under āctrēo in þām eorðscræfe.

Eald is þes eorðsele, eal ic eom oflongad,

sindon dena dimme, dūna ūphēa,

bitre burgtūnas, brērum beweaxne,

wīc wynna lēas. Ful oft mec hēr wrāþe begeat

fromsīþ frēan. Frȳnd sind on eorþan,

lēofe lifgende, leger weardiað,

þonne ic on uhtan āna gonge

under āctrēo geond þās eorðscrafu.

Þǣr ic sittan mōt sumorlangne dæg,

þǣr ic wēpan mæg mīne wræcsīþas,

earfoþa fela; forþon ic ǣfre ne mæg

þǣre mōdceare mīnre gerestan,

ne ealles þæs longaþes þe mec on þissum līfe begeat.

Ā scyle geong mon wesan gēomormōd,

heard heortan geþōht, swylce habban sceal

blīþe gebǣro, ēac þon brēostceare,

sinsorgna gedreag. Sȳ æt him sylfum gelong

eal his worulde wyn, sȳ ful wīde fāh

feorres folclondes, þæt mīn frēond siteð

under stānhliþe storme behrīmed,

wine wērigmōd, wætre beflōwen

on drēorsele, drēogeð se mīn wine

micle mōdceare; hē gemon tō oft

wynlicran wīc. Wā bið þām þe sceal

of langoþe lēofes ābīdan.

envoyé par Riccardo Venturi - 1/11/2014 - 23:56

Langue: anglo-saxon (ca.450-1100)

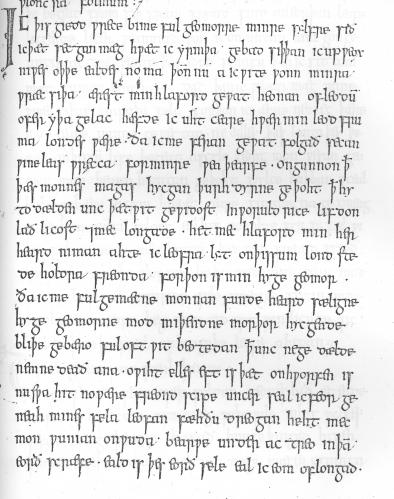

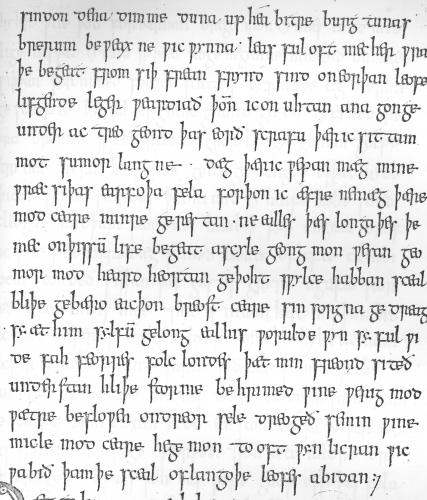

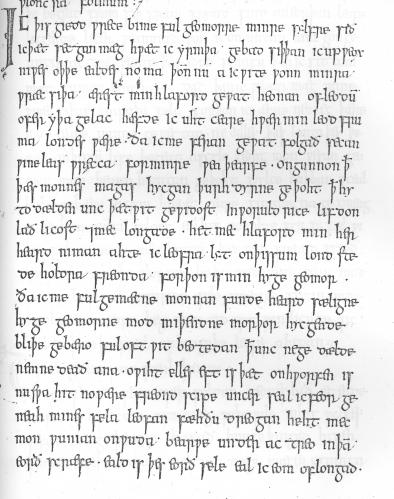

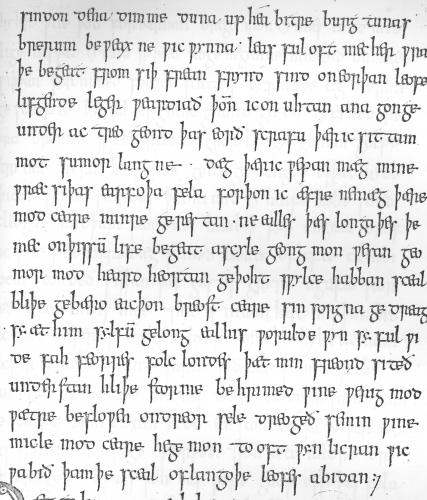

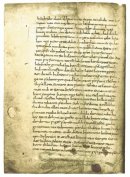

Il testo così come compare nel manoscritto.

Codex Exoniens, ff. 115a/115b

Codex Exoniens, ff. 115a/115b

Fino ad oggi (2.11.14) è stato quello, ricavato dalla Wife's Lament Page proposto come testo principale di questa pagina per alcune difficoltà che il suo autore (Bernart Bartleby) aveva nel riprodurre correttamete la particolare pratica della suddivisione dei due semiversi allitteranti propri della poesia anglosassone. Naturalmente, proporre un testo in tale veste grafica ha un carattere puramente filologico (si tratta, in pratica, di una vera e propria edizione diplomatica). Lo riproduciamo a parte, dopo i testi editi, accompagnato dalle fotografie del manoscritto originale a mo' di confronto. [RV]

Ic þis giedd wrece bime ful geomorre minre sylfre sið

ic þæt secgan mæg hwæt ic yrmþa gebad siþþan icupweox

niwes oþþe ealdes noma þon nu aicwite wonn minra

wræcsiþa ærest minhlaford gewat heonan ofleodum

ofer yþa gelac hæfde ic uht ceare hwærmin leodfru

ma londes wære. ða icme feran gewat folgað secan

wineleas wræcca forminre weaþearfe. Ongunnon þæt

þæs monnes magas hycgan þurh dyrne geþoht þæthy

todælden unc þætwit gewidost inworuldrice lifdon

laðlicost ondmec longade. Hetmec hlaford min her

heard niman ahte icleofra lyt onþissum londste

de holdra freonda forþonismin hyge geomor.

ðaicme fulgemæcne monnan funde heard sæligne

hyge geomorne mod miþendne morþor hycgendne

bliþe gebæro fuloftwit beotedan þætunc nege dælde

nemne deað ana. owiht elles eft isþæt onhworfen is

nuswa hit nowære freond scipe uncer scealicfeor ge

neah mines fela leofan fæhðu dreogan heht mec

mon wunian onwuda bearwe under actreo inþam

eorð scræfe. Eald is þes eorð sele eal iceom oflongad.

sindon dena dimme duna upheabitre burgtunas

brerum beweax ne wicwynna leas ful oft mecher wra

þe begeat from siþ frean frynd sind oneorþan leofe

lifgende leger weardiað þonne icon uhtan ana gonge

under ac treo geond þas eorð scrafu þæric sittan

mot sumor langne. dæg þæric wepan mæg mine

wræcsiþas earfoþa fela forþonic æfre nemæg þære

modceare minre gerestan. neealles þæs longaþes þe

mec onþissum life begeat ascyle geong mon wesan geo

mor mod heard heortan geþoht swylce habban sceal

bliþe gebæro eacþon breost ceare sinsorgna gedreag

syæthim sylfum gelong ealhis worulde wyn syfulwi

de fah feorres folc londes þætmin freond siteð

understan hliþe storme behrimed wine werig mod

wætre beflowen ondreor sele dreogeð semin wine

micle mod ceare hegemon tooft wynlicran wic

wabið þamþe sceal oflangoþe leofes abidan.

ic þæt secgan mæg hwæt ic yrmþa gebad siþþan icupweox

niwes oþþe ealdes noma þon nu aicwite wonn minra

wræcsiþa ærest minhlaford gewat heonan ofleodum

ofer yþa gelac hæfde ic uht ceare hwærmin leodfru

ma londes wære. ða icme feran gewat folgað secan

wineleas wræcca forminre weaþearfe. Ongunnon þæt

þæs monnes magas hycgan þurh dyrne geþoht þæthy

todælden unc þætwit gewidost inworuldrice lifdon

laðlicost ondmec longade. Hetmec hlaford min her

heard niman ahte icleofra lyt onþissum londste

de holdra freonda forþonismin hyge geomor.

ðaicme fulgemæcne monnan funde heard sæligne

hyge geomorne mod miþendne morþor hycgendne

bliþe gebæro fuloftwit beotedan þætunc nege dælde

nemne deað ana. owiht elles eft isþæt onhworfen is

nuswa hit nowære freond scipe uncer scealicfeor ge

neah mines fela leofan fæhðu dreogan heht mec

mon wunian onwuda bearwe under actreo inþam

eorð scræfe. Eald is þes eorð sele eal iceom oflongad.

sindon dena dimme duna upheabitre burgtunas

brerum beweax ne wicwynna leas ful oft mecher wra

þe begeat from siþ frean frynd sind oneorþan leofe

lifgende leger weardiað þonne icon uhtan ana gonge

under ac treo geond þas eorð scrafu þæric sittan

mot sumor langne. dæg þæric wepan mæg mine

wræcsiþas earfoþa fela forþonic æfre nemæg þære

modceare minre gerestan. neealles þæs longaþes þe

mec onþissum life begeat ascyle geong mon wesan geo

mor mod heard heortan geþoht swylce habban sceal

bliþe gebæro eacþon breost ceare sinsorgna gedreag

syæthim sylfum gelong ealhis worulde wyn syfulwi

de fah feorres folc londes þætmin freond siteð

understan hliþe storme behrimed wine werig mod

wætre beflowen ondreor sele dreogeð semin wine

micle mod ceare hegemon tooft wynlicran wic

wabið þamþe sceal oflangoþe leofes abidan.

envoyé par Riccardo Venturi - 2/11/2014 - 00:08

Langue: italien

La traduzione italiana di Roberto Sanesi.

Tratta da: Poemi Anglosassoni VI-X Secolo, traduzione, introduzione, note e bibliografia a cura di Roberto Sanesi. Ugo Guanda editore, Parma, 1975 [Riedizione dalle Edizioni Lerici, 1964]. La traduzione si trova alle pagine 102/103. Si riproduce qui anche la breve nota introduttiva al componimento, a pagina XLVII dell'introduzione:

"Il lamento, 53 versi contenuti nei fogli 115a-115b del Codex Exoniensis, presenta numerose difficoltà di interpretazione, e ancora non si è giunti a una lettura chiara e definitiva del testo. I primi studiosi hanno messo questa elegia in relazione al Messaggio del Marito Lontano, che la segue nel codice a distanza di sette fogli, ma il suo contenuto, ricostruito ragionevolmente dallo Stefanovic, nega ogni possibilità di accordo tra i due testi. La 'storia' di cui è protagonista il personaggio femminile dell'elegia è così riassunta dallo Stefanovic: 'Un uomo parte per un viaggio al di là dei mari. La moglie sta in pensiero per lui. I parenti di lui complottano per separarli. Anche la moglie lascia la casa. Ritrova il marito in un luogo in cui non aveva amici. Il piano dei parenti è riuscito. L'unione amorosa dei due è spezzata. Il marito infligge alla moglie una punizione, come se la moglie fosse rea di adulterio. La caccia in esilio in una foresta dove essa vive in una caverna e piange il suo dolore, augurando a un giovane che gli accada ciò che lei ha sofferto per causa sua -il dolore e le pene e la separazione dalle sue gioie. Allora lei pensa anche al marito che vive solitario in una casa vuota e desolata, e che deve soffrire grandi pene quando ricorda la casa di un tempo colma di gioie."

"Il lamento, 53 versi contenuti nei fogli 115a-115b del Codex Exoniensis, presenta numerose difficoltà di interpretazione, e ancora non si è giunti a una lettura chiara e definitiva del testo. I primi studiosi hanno messo questa elegia in relazione al Messaggio del Marito Lontano, che la segue nel codice a distanza di sette fogli, ma il suo contenuto, ricostruito ragionevolmente dallo Stefanovic, nega ogni possibilità di accordo tra i due testi. La 'storia' di cui è protagonista il personaggio femminile dell'elegia è così riassunta dallo Stefanovic: 'Un uomo parte per un viaggio al di là dei mari. La moglie sta in pensiero per lui. I parenti di lui complottano per separarli. Anche la moglie lascia la casa. Ritrova il marito in un luogo in cui non aveva amici. Il piano dei parenti è riuscito. L'unione amorosa dei due è spezzata. Il marito infligge alla moglie una punizione, come se la moglie fosse rea di adulterio. La caccia in esilio in una foresta dove essa vive in una caverna e piange il suo dolore, augurando a un giovane che gli accada ciò che lei ha sofferto per causa sua -il dolore e le pene e la separazione dalle sue gioie. Allora lei pensa anche al marito che vive solitario in una casa vuota e desolata, e che deve soffrire grandi pene quando ricorda la casa di un tempo colma di gioie."

IL LAMENTO DELLA MOGLIE ESILIATA

Canto questo lamento di me misera, e della

mia dolorosa esperienza, e posso dire

che tutte le mie afflizioni antiche e nuove

sopportate da me da quando sono donna

non furono mai così atroci come lo sono ora.

Sempre nella mia vita ho dovuto combattere

contro durissime pene. Il mio signore un giorno

partì sopra le onde che si frangono, abbandonò il suo popolo,

e io rimasi insonne nell'angoscia, e mi chiedevo

in quali terre il mio principe vivesse.

Allora anch'io me ne andai, misera e senza amici,

alla ricerca d'un nobile che mi potesse accogliere

al suo servizio. Ma i più vicini congiunti

di mio marito, in segreto consiglio,

complottarono contro di noi per poterci dividere,

perché su questa terra vivessimo nell'odio,

l'uno dall'altra separati, mentre mi consumavo

per amore di lui. Ma il mio spietato signore

ordinò che venissi condotta

in questa terra dove non ho amici

leali, o sinceri compagni, e il mio cuore è triste,

perché ho scoperto che l'uomo che a me si addiceva

è di animo cupo e cuore miserabile,

nasconde i suoi pensieri e medita un delitto.

Con volto sempre sereno avevamo giurato

che soltanto la morte ci avrebbe separati.

Come tutto è mutato da allora: il nostro amore

è come se non fosse mai esistito.

Vicino o lontano che sia, ora devo soffrire

l'odio del mio signore tanto amato.

Fui costretta a passare la vita

nella caverna scavata nella terra,

sotto la quercia nel folto del bosco,

e la caverna è antica, e mi consumo d'amore per lui.

Vi sono oscure vallate e ripide colline,

tetre foreste simili a fortezze, coperte di rovi -

una triste dimora. L'assenza del mio sposo

spesso mi affligge amaramente. Nel mondo

vi sono amanti che vivono, e si dividono un letto,

l'uno all'altro cari; io solitaria nell'alba

cammino fra queste caverne nascoste dalle querce.

Durante il lungo giorno dell'estate

resto seduta a piangere tutte le mie miserie,

tutti i miei duri affanni. Per questo non potrò

mai trovare riposo all'ansia del mio spirito,

nessuna quiete alla pena che affligge la mia vita.

Sia sempre triste l'animo di quel giovane,

e amari i suoi pensieri; per quanto lieto il suo volto,

possa provare il peso dell'angoscia, l'atroce tormento

di un continuo dolore. E la sua gioia mondana

sia disprezzata ovunque, ed egli stesso sia

esiliato in paesi lontani; perché il mio amante, il mio

sconsolato signore sta sotto dirupi di roccia,

e lo copre il nevischio di forti bufere, le acque lo circondano

in luoghi dolorosi. Il mio signore soffre,

gli affanni lo tormentano, ché troppo spesso ricorda

una dimora più lieta. Amare pene pesano

su chi inutilmente si strugge per il suo amore lontano.

Canto questo lamento di me misera, e della

mia dolorosa esperienza, e posso dire

che tutte le mie afflizioni antiche e nuove

sopportate da me da quando sono donna

non furono mai così atroci come lo sono ora.

Sempre nella mia vita ho dovuto combattere

contro durissime pene. Il mio signore un giorno

partì sopra le onde che si frangono, abbandonò il suo popolo,

e io rimasi insonne nell'angoscia, e mi chiedevo

in quali terre il mio principe vivesse.

Allora anch'io me ne andai, misera e senza amici,

alla ricerca d'un nobile che mi potesse accogliere

al suo servizio. Ma i più vicini congiunti

di mio marito, in segreto consiglio,

complottarono contro di noi per poterci dividere,

perché su questa terra vivessimo nell'odio,

l'uno dall'altra separati, mentre mi consumavo

per amore di lui. Ma il mio spietato signore

ordinò che venissi condotta

in questa terra dove non ho amici

leali, o sinceri compagni, e il mio cuore è triste,

perché ho scoperto che l'uomo che a me si addiceva

è di animo cupo e cuore miserabile,

nasconde i suoi pensieri e medita un delitto.

Con volto sempre sereno avevamo giurato

che soltanto la morte ci avrebbe separati.

Come tutto è mutato da allora: il nostro amore

è come se non fosse mai esistito.

Vicino o lontano che sia, ora devo soffrire

l'odio del mio signore tanto amato.

Fui costretta a passare la vita

nella caverna scavata nella terra,

sotto la quercia nel folto del bosco,

e la caverna è antica, e mi consumo d'amore per lui.

Vi sono oscure vallate e ripide colline,

tetre foreste simili a fortezze, coperte di rovi -

una triste dimora. L'assenza del mio sposo

spesso mi affligge amaramente. Nel mondo

vi sono amanti che vivono, e si dividono un letto,

l'uno all'altro cari; io solitaria nell'alba

cammino fra queste caverne nascoste dalle querce.

Durante il lungo giorno dell'estate

resto seduta a piangere tutte le mie miserie,

tutti i miei duri affanni. Per questo non potrò

mai trovare riposo all'ansia del mio spirito,

nessuna quiete alla pena che affligge la mia vita.

Sia sempre triste l'animo di quel giovane,

e amari i suoi pensieri; per quanto lieto il suo volto,

possa provare il peso dell'angoscia, l'atroce tormento

di un continuo dolore. E la sua gioia mondana

sia disprezzata ovunque, ed egli stesso sia

esiliato in paesi lontani; perché il mio amante, il mio

sconsolato signore sta sotto dirupi di roccia,

e lo copre il nevischio di forti bufere, le acque lo circondano

in luoghi dolorosi. Il mio signore soffre,

gli affanni lo tormentano, ché troppo spesso ricorda

una dimora più lieta. Amare pene pesano

su chi inutilmente si strugge per il suo amore lontano.

envoyé par Riccardo Venturi - 2/11/2014 - 12:10

Langue: italien

Traduzione italiana di Giuseppe Brunetti.

Reperita dal sito dell’Università di Padova, Dipartimento degli Studi Linguistici e Letterari. Giuseppe Brunetti è stato ordinario di letteratura inglese presso l'università di Padova.

IL LAMENTO DELLA MOGLIE

Di me tristissima riferisco questa storia,

le mie vicissitudini. Posso dire

che affanni ho sofferto da adulta,

in passato o di recente, mai più di adesso –

sempre ho patito il tormento delle mie sventure.

Dapprima il mio signore andò via dalla sua gente

oltre il tumulto delle onde; all’alba penavo

al pensiero di dove fosse il capo d’uomini.

Quando partii per cercare il seguito,

derelitta senza amici, in doloroso bisogno,

i parenti dell’uomo si proposero

di separarci per un segreto intento,

cosicché lontanissimi abbiamo vissuto

al mondo infelicissimi, e io mi struggevo di desiderio.

Il mio signore m’ordinò di prender dimora qui,

ho avuto pochi amici, diletti e fedeli,

in questa contrada. Perciò è triste il mio animo,

quando ho trovato che l’uomo a me appropriato

è sfortunato, triste nell’animo,

cela il suo intento meditando atti crudeli.

Con lieto contegno ci promettemmo spesso

che solo la morte ci avrebbe separati,

nient’ altro; poi è tutto cambiato,

[annullato] ora, come se mai fosse stata,

la nostra amicizia. Lontana o vicina

patirò l’inimicizia del tanto amato.

L’uomo m’ha ordinato di dimorare in un folto

d’alberi, sotto una quercia in un antro.

Antica è questa sala di terra, e io tutta mi struggo.

Sono cupe le valli, scoscesi i monti,

aspra la cinta, coperta di rovi,

dimora senza gioia. Qui spesso crudele mi colse

la dipartita del signore. Sono in terra amici,

vivono amanti, tengono il letto,

quando all’alba io vago sola

sotto la quercia per questi antri.

Là posso sedere lunghi giorni,

là piangere le mie sventure,

i molti affanni. Perciò mai posso

aver requie della mia pena,

né dello struggimento che mi ha colto in questa vita.

Sarà forse sempre triste il giovane,

duro l’intento del cuore, e ad un tempo avrà

lieto contegno, oltre ad affanno,

ressa d’incessanti dolori, sia che da lui stesso dipenda

tutta la sua gioia al mondo, o sia in largo reietto

in paese lontano, cosicché il mio amico siede

sotto una scogliera coperto da gelo di tempesta,

l’amico affranto, avvolto d’acqua

in dimora desolata. Soffrirà il mio amico

grandi affanni – ricorderà troppo spesso

dimora più felice. Male a chi deve

struggendosi aspettare l’amato.

Di me tristissima riferisco questa storia,

le mie vicissitudini. Posso dire

che affanni ho sofferto da adulta,

in passato o di recente, mai più di adesso –

sempre ho patito il tormento delle mie sventure.

Dapprima il mio signore andò via dalla sua gente

oltre il tumulto delle onde; all’alba penavo

al pensiero di dove fosse il capo d’uomini.

Quando partii per cercare il seguito,

derelitta senza amici, in doloroso bisogno,

i parenti dell’uomo si proposero

di separarci per un segreto intento,

cosicché lontanissimi abbiamo vissuto

al mondo infelicissimi, e io mi struggevo di desiderio.

Il mio signore m’ordinò di prender dimora qui,

ho avuto pochi amici, diletti e fedeli,

in questa contrada. Perciò è triste il mio animo,

quando ho trovato che l’uomo a me appropriato

è sfortunato, triste nell’animo,

cela il suo intento meditando atti crudeli.

Con lieto contegno ci promettemmo spesso

che solo la morte ci avrebbe separati,

nient’ altro; poi è tutto cambiato,

[annullato] ora, come se mai fosse stata,

la nostra amicizia. Lontana o vicina

patirò l’inimicizia del tanto amato.

L’uomo m’ha ordinato di dimorare in un folto

d’alberi, sotto una quercia in un antro.

Antica è questa sala di terra, e io tutta mi struggo.

Sono cupe le valli, scoscesi i monti,

aspra la cinta, coperta di rovi,

dimora senza gioia. Qui spesso crudele mi colse

la dipartita del signore. Sono in terra amici,

vivono amanti, tengono il letto,

quando all’alba io vago sola

sotto la quercia per questi antri.

Là posso sedere lunghi giorni,

là piangere le mie sventure,

i molti affanni. Perciò mai posso

aver requie della mia pena,

né dello struggimento che mi ha colto in questa vita.

Sarà forse sempre triste il giovane,

duro l’intento del cuore, e ad un tempo avrà

lieto contegno, oltre ad affanno,

ressa d’incessanti dolori, sia che da lui stesso dipenda

tutta la sua gioia al mondo, o sia in largo reietto

in paese lontano, cosicché il mio amico siede

sotto una scogliera coperto da gelo di tempesta,

l’amico affranto, avvolto d’acqua

in dimora desolata. Soffrirà il mio amico

grandi affanni – ricorderà troppo spesso

dimora più felice. Male a chi deve

struggendosi aspettare l’amato.

envoyé par Bernart Bartleby - 9/7/2014 - 09:42

Langue: anglais

Traduzione inglese di Michael R. Burch

Modern English translation by Michael R. Burch

Modern English translation by Michael R. Burch

The Wife's Lament or The Wife's Complaint is an Old English poem of 53 lines found in the Exeter Book and generally treated as an elegy in the manner of the German Frauenlied, or woman's song. The poem has been relatively well-preserved and requires few if any emendations to enable an initial reading. Thematically, the poem is primarily concerned with the evocation of the grief of the female speaker and with the representation of her state of despair. The tribulations she suffers leading to her state of lamentation, however, are cryptically described and have been subject to a wide array of interpretations.`

Though the description of the text as a woman's song or Frauenlied —lamenting for a lost or absent lover— is the dominant understanding of the poem, the text has nevertheless been subject to a variety of distinct treatments that fundamentally disagree with this view and propose alternatives. One such treatment considers the poem to be allegory, in which interpretation the lamenting speaker represents the Church as Bride of Christ or as an otherwise feminine allegorical figure. Another dissenting interpretation holds that the speaker, who describes herself held within an old earth cell (eald is þes eorðsele) beneath an oak tree (under actreo), may indeed literally be located in a cell under the earth, and would therefore constitute a voice of the deceased, speaking from beyond the grave. Both the interpretations, as with most alternatives, face difficulties, particularly in the latter case, for which no analogous texts exist in the Old English corpus.

The status of the poem as a lament spoken by a female protagonist is therefore fairly well established in criticism. Interpretations that attempt a treatment diverging from this, though diverse in their approach, bear a fairly heavy burden of proof. Thematic consistencies between the Wife's Lament and its close relative in the genre of the woman's song, as well as close neighbour in the Exeter Book, Wulf and Eadwacer, make unconventional treatments somewhat counterintuitive. A final point of divergence, however, between the conventional interpretation and variants proceeds from the similarity of the poem in some respects to elegiac poems in the Old English corpus that feature male protagonists. Similarities between the language and circumstances of the male protagonist of The Wanderer, for example, and the protagonist of the Wife's Lament have led other critics to argue, even more radically, that the protagonist of the poem (to which the attribution of the title "the wife's lament" is wholly apocryphal and fairly recent) may in fact be male. This interpretation, however, faces the almost insurmountable problem that adjectives and personal nouns occurring within the poem (geomorre, minre, sylfre) are feminine in grammatical gender. This interpretation is at the very least dependent therefore on a contention that perhaps a later Anglo-Saxon copyist has wrongly imposed feminine gender on the protagonist where this was not the original authorial intent, and such contentions almost wholly relegate discussion to the realm of the hypothetical. It is also thought by some that the Wife's Lament and the Husband's Message may be part of a larger work.

The poem is also considered by some to be a riddle poem. A riddle poem contains a lesson told in cultural context which would be understandable or relates to the reader, and was a very popular genre of poetry of the time period. Gnomic wisdom is also a characteristic of a riddle poem, and is present in the poem's closing sentiment (lines 52-53). Also, it cannot be ignored that contained within the Exeter Book are 92 other riddle poems. According to literary scholar Faye Walker-Pelkey, "The Lament's placement in the Exeter Book, its mysterious content, its fragmented structure, its similarities to riddles, and its inclusion of gnomic wisdom suggest that the "elegy"...is a riddle."

Interpreting the text of the poem as a woman's lament, many of the text's central controversies bear a similarity to those around Wulf and Eadwacer. Although it is unclear whether the protagonist's tribulations proceed from relationships with multiple lovers or a single man, Stanley B. Greenfield, in his paper "The Wife's Lament Reconsidered," discredits the claim that the poem involves multiple lovers. He suggests that lines 42-47 use an optative voice as a curse against the husband, not a second lover. The impersonal expressions with which the poem concludes, according to Greenfield, do not represent gnomic wisdom or even a curse upon young men in general; rather this impersonal voice is used to convey the complex emotions of the wife toward her husband.

Virtually all of the facts integral to the poem beyond the matter of genre are widely open to dispute. The obscurity of the narrative background of the story has led some critics to suggest that the narrative may have been one familiar to its original listeners, at some point when this particular rendition was conceived, such that much of the matter of the story was omitted in favour of a focus on the emotional drive of the lament. Constructing a coherent narrative from the text requires a good deal of inferential conjecture, but a commentary on various elements of the text is provided here nonetheless.

The Wife's Lament, even more so than Wulf and Eadwacer, vividly conflates the theme of mourning over a departed or deceased leader of the people (as may be found in The Wanderer) with the theme of mourning over a departed or deceased lover (as portrayed in Wulf and Eadwacer). The lord of the speaker's people (min leodfruma, min hlaford) appears in all likelihood also to be her lord in marriage. Given that her lord's kinsmen (þæt monnes magas) are described as taking measures to separate the speaker from him, a probable interpretation of the speaker's initial circumstances is that she has been entered into an exogamous relationship typical within the Anglo-Saxon heroic tradition, and her marital status has left her isolated among her husband's people, who are hostile to her, whether due to her actions or merely due to political strife beyond her control. Somewhat confusing the account, however, the speaker, longing for her lover, has apparently departed (Ic me feran gewat) either to seek out her lord or merely to seek exile, and the relationship, chronologically or causally, between this act and the hostility of her and/or her husband's people is unclear.

She is told by her lord (hlaford min) to take up a particular dwelling place, where she encounters a man of unclear identity, who is or was "suitable" (ful gemæcne) to her, and they declare they will not be separated by anything save death. This, however, does not last, seemingly as a consequence of prior difficulties concerning her marriage. The remainder of the narrative concerns her lamentable state in the present of the poem. She is commanded to dwell in a barrow within the earth (þes eorðsele), wherein she is compelled to mourn the loss of her lord and her present exile. The poem concludes with what begins as a gnomic exhortation admonishing youth to adopt a cheerful aspect, even in grief, but subsequently develops into an expression of the grief of the speaker's beloved.

More recent interpretations have disputed this gnomic exhortation. According to John Niles, in this “genteel” reading, it seems less consequential whether the wife has been scorned by one husband or two; it is her “dignified passivity” as well as her gnomic wisdom on which scholars focus. In “vindictive” readings, however, the wife is generally seen to burn with anger toward one man – her husband. In such views, The Wife’s Lament begins as a bold statement of misery, transitions into a description of her misfortunes in which she nostalgically recalls happy days with her husband, and ends in a bitter curse upon this same man who has now abandoned her.

One proponent of this approach is Barrie Ruth Straus, author of “Women’s Words as Weapons: Speech as Action in ‘The Wife’s Lament.’” Straus bases her analysis of the poem on the speech act theory of J.L. Austin and John Searle, which regards speech as an action. Strauss breaks the poem into sections and shows how the language or “illocutionary acts” of each can be seen as an assertive act of telling. In a world in which women have little control, Straus emphasizes how speech could be an act of power; thus in the first section, the narrator deliberately establishes an intent to tell her story. She then persuasively presents her story as one of being wronged by her husband, avenging herself in the telling. In light of this speech act theory, Straus concludes that the final ten lines of the poem should be construed as a curse upon the husband, as this is the “least problematic interpretation”.

Like Straus, Niles views the poem as an aggressive act of speech. While arguing that the poem presents certain philological evidence to support an optative reading, the bulk of his support comes from contextual analysis of the act of cursing within the Anglo-Saxon culture. His article, “The Problem of the Ending of the Wife’s ‘Lament’ ” provides an intriguing overview of curses, discussing biblical influences of cursing as seen in Psalms 108 and the book of Deuteronomy. He also examines the act of cursing in charters and wills, quoting examples such as the following: “If anyone ever alters or removes anything in this will, may God’s grace and his eternal reward be taken from him forever…”. The Exeter Book itself is inscribed with such a curse. The Anglo-Saxon culture that took all acts of wearg-cwedol (evil speaking) very seriously and even warily watched for potential witches, Niles argues, would have little trouble accepting the poem as a curse. Whether intended as a formal malediction or an emotional vituperation is less important. - en.wikipedia

Though the description of the text as a woman's song or Frauenlied —lamenting for a lost or absent lover— is the dominant understanding of the poem, the text has nevertheless been subject to a variety of distinct treatments that fundamentally disagree with this view and propose alternatives. One such treatment considers the poem to be allegory, in which interpretation the lamenting speaker represents the Church as Bride of Christ or as an otherwise feminine allegorical figure. Another dissenting interpretation holds that the speaker, who describes herself held within an old earth cell (eald is þes eorðsele) beneath an oak tree (under actreo), may indeed literally be located in a cell under the earth, and would therefore constitute a voice of the deceased, speaking from beyond the grave. Both the interpretations, as with most alternatives, face difficulties, particularly in the latter case, for which no analogous texts exist in the Old English corpus.

The status of the poem as a lament spoken by a female protagonist is therefore fairly well established in criticism. Interpretations that attempt a treatment diverging from this, though diverse in their approach, bear a fairly heavy burden of proof. Thematic consistencies between the Wife's Lament and its close relative in the genre of the woman's song, as well as close neighbour in the Exeter Book, Wulf and Eadwacer, make unconventional treatments somewhat counterintuitive. A final point of divergence, however, between the conventional interpretation and variants proceeds from the similarity of the poem in some respects to elegiac poems in the Old English corpus that feature male protagonists. Similarities between the language and circumstances of the male protagonist of The Wanderer, for example, and the protagonist of the Wife's Lament have led other critics to argue, even more radically, that the protagonist of the poem (to which the attribution of the title "the wife's lament" is wholly apocryphal and fairly recent) may in fact be male. This interpretation, however, faces the almost insurmountable problem that adjectives and personal nouns occurring within the poem (geomorre, minre, sylfre) are feminine in grammatical gender. This interpretation is at the very least dependent therefore on a contention that perhaps a later Anglo-Saxon copyist has wrongly imposed feminine gender on the protagonist where this was not the original authorial intent, and such contentions almost wholly relegate discussion to the realm of the hypothetical. It is also thought by some that the Wife's Lament and the Husband's Message may be part of a larger work.

The poem is also considered by some to be a riddle poem. A riddle poem contains a lesson told in cultural context which would be understandable or relates to the reader, and was a very popular genre of poetry of the time period. Gnomic wisdom is also a characteristic of a riddle poem, and is present in the poem's closing sentiment (lines 52-53). Also, it cannot be ignored that contained within the Exeter Book are 92 other riddle poems. According to literary scholar Faye Walker-Pelkey, "The Lament's placement in the Exeter Book, its mysterious content, its fragmented structure, its similarities to riddles, and its inclusion of gnomic wisdom suggest that the "elegy"...is a riddle."

Interpreting the text of the poem as a woman's lament, many of the text's central controversies bear a similarity to those around Wulf and Eadwacer. Although it is unclear whether the protagonist's tribulations proceed from relationships with multiple lovers or a single man, Stanley B. Greenfield, in his paper "The Wife's Lament Reconsidered," discredits the claim that the poem involves multiple lovers. He suggests that lines 42-47 use an optative voice as a curse against the husband, not a second lover. The impersonal expressions with which the poem concludes, according to Greenfield, do not represent gnomic wisdom or even a curse upon young men in general; rather this impersonal voice is used to convey the complex emotions of the wife toward her husband.

Virtually all of the facts integral to the poem beyond the matter of genre are widely open to dispute. The obscurity of the narrative background of the story has led some critics to suggest that the narrative may have been one familiar to its original listeners, at some point when this particular rendition was conceived, such that much of the matter of the story was omitted in favour of a focus on the emotional drive of the lament. Constructing a coherent narrative from the text requires a good deal of inferential conjecture, but a commentary on various elements of the text is provided here nonetheless.

The Wife's Lament, even more so than Wulf and Eadwacer, vividly conflates the theme of mourning over a departed or deceased leader of the people (as may be found in The Wanderer) with the theme of mourning over a departed or deceased lover (as portrayed in Wulf and Eadwacer). The lord of the speaker's people (min leodfruma, min hlaford) appears in all likelihood also to be her lord in marriage. Given that her lord's kinsmen (þæt monnes magas) are described as taking measures to separate the speaker from him, a probable interpretation of the speaker's initial circumstances is that she has been entered into an exogamous relationship typical within the Anglo-Saxon heroic tradition, and her marital status has left her isolated among her husband's people, who are hostile to her, whether due to her actions or merely due to political strife beyond her control. Somewhat confusing the account, however, the speaker, longing for her lover, has apparently departed (Ic me feran gewat) either to seek out her lord or merely to seek exile, and the relationship, chronologically or causally, between this act and the hostility of her and/or her husband's people is unclear.

She is told by her lord (hlaford min) to take up a particular dwelling place, where she encounters a man of unclear identity, who is or was "suitable" (ful gemæcne) to her, and they declare they will not be separated by anything save death. This, however, does not last, seemingly as a consequence of prior difficulties concerning her marriage. The remainder of the narrative concerns her lamentable state in the present of the poem. She is commanded to dwell in a barrow within the earth (þes eorðsele), wherein she is compelled to mourn the loss of her lord and her present exile. The poem concludes with what begins as a gnomic exhortation admonishing youth to adopt a cheerful aspect, even in grief, but subsequently develops into an expression of the grief of the speaker's beloved.

More recent interpretations have disputed this gnomic exhortation. According to John Niles, in this “genteel” reading, it seems less consequential whether the wife has been scorned by one husband or two; it is her “dignified passivity” as well as her gnomic wisdom on which scholars focus. In “vindictive” readings, however, the wife is generally seen to burn with anger toward one man – her husband. In such views, The Wife’s Lament begins as a bold statement of misery, transitions into a description of her misfortunes in which she nostalgically recalls happy days with her husband, and ends in a bitter curse upon this same man who has now abandoned her.

One proponent of this approach is Barrie Ruth Straus, author of “Women’s Words as Weapons: Speech as Action in ‘The Wife’s Lament.’” Straus bases her analysis of the poem on the speech act theory of J.L. Austin and John Searle, which regards speech as an action. Strauss breaks the poem into sections and shows how the language or “illocutionary acts” of each can be seen as an assertive act of telling. In a world in which women have little control, Straus emphasizes how speech could be an act of power; thus in the first section, the narrator deliberately establishes an intent to tell her story. She then persuasively presents her story as one of being wronged by her husband, avenging herself in the telling. In light of this speech act theory, Straus concludes that the final ten lines of the poem should be construed as a curse upon the husband, as this is the “least problematic interpretation”.

Like Straus, Niles views the poem as an aggressive act of speech. While arguing that the poem presents certain philological evidence to support an optative reading, the bulk of his support comes from contextual analysis of the act of cursing within the Anglo-Saxon culture. His article, “The Problem of the Ending of the Wife’s ‘Lament’ ” provides an intriguing overview of curses, discussing biblical influences of cursing as seen in Psalms 108 and the book of Deuteronomy. He also examines the act of cursing in charters and wills, quoting examples such as the following: “If anyone ever alters or removes anything in this will, may God’s grace and his eternal reward be taken from him forever…”. The Exeter Book itself is inscribed with such a curse. The Anglo-Saxon culture that took all acts of wearg-cwedol (evil speaking) very seriously and even warily watched for potential witches, Niles argues, would have little trouble accepting the poem as a curse. Whether intended as a formal malediction or an emotional vituperation is less important. - en.wikipedia

THE WIFE’S LAMENT

I draw these words from deep wells of wild grief,

care-worn, unutterably sad.

I can recount woes I've borne since birth,

present and past, till I was driven mad.

I have won, from my exile-paths, only pain

here on earth.

First, my lord forsook his kin-folk, left,

crossed the seas' wide expanse, abandoning our tribe.

Since then, I've known only misery ...

wrenching dawn-griefs, despair in wild tides;

where, oh where can he be?

Then I, too, left—a lonely, lordless refugee,

full of unaccountable desires!

But the man's kinsmen schemed secretly

to estrange us, divide us, keep us apart, divorced from hope,

unable to touch, and my heart broke ...

Then my lord spoke:

"Take up residence here."

I had few acquaintances in this alien region, none close.

I was penniless, friendless;

Christ, I felt lost!

Eventually

I thought I had found a well-matched man—one meant for me,

but unfortunately he

was ill-starred and blind,

with a devious mind,

full of murderous intentions,

plotting some crime!

Before God we

vowed never to part, not till kingdom come, never!

But now that's all changed, forever—

our marriage is done, severed.

So now I must hear, far and near,

contempt for my husband.

Then other men bade me, "Go, live in repentance in the sacred grove,

beneath the great oak trees, in a grotto, alone."

Now in this ancient earth-cave I am lost and oppressed—

the valleys are dark, the hills strange, wild, immense,

and this cruel-briared enclosure—an arid abode!

Now the injustice assails me—my lord's absence!

Elsewhere on earth lovers share the same bed

while I pass through life dead,

in this dark abscess where I wilt in the heat, unable to rest

or forget the sorrows of my life's hard lot.

A young woman must always be

stern, hard-of-heart, unmoved, full of belief,

enduring breast-cares, suppressing her own feelings.

She must appear cheerful

even in a tumult of grief.

Now, like a criminal exiled to a far-off land,

moaning beneath insurmountable cliffs,

my weary-minded love, drenched by wild storms

and caught in the clutches of anguish, mourns,

reminded constantly of our former happiness.

Woe be it to them who abide in longing.

I draw these words from deep wells of wild grief,

care-worn, unutterably sad.

I can recount woes I've borne since birth,

present and past, till I was driven mad.

I have won, from my exile-paths, only pain

here on earth.

First, my lord forsook his kin-folk, left,

crossed the seas' wide expanse, abandoning our tribe.

Since then, I've known only misery ...

wrenching dawn-griefs, despair in wild tides;

where, oh where can he be?

Then I, too, left—a lonely, lordless refugee,

full of unaccountable desires!

But the man's kinsmen schemed secretly

to estrange us, divide us, keep us apart, divorced from hope,

unable to touch, and my heart broke ...

Then my lord spoke:

"Take up residence here."

I had few acquaintances in this alien region, none close.

I was penniless, friendless;

Christ, I felt lost!

Eventually

I thought I had found a well-matched man—one meant for me,

but unfortunately he

was ill-starred and blind,

with a devious mind,

full of murderous intentions,

plotting some crime!

Before God we

vowed never to part, not till kingdom come, never!

But now that's all changed, forever—

our marriage is done, severed.

So now I must hear, far and near,

contempt for my husband.

Then other men bade me, "Go, live in repentance in the sacred grove,

beneath the great oak trees, in a grotto, alone."

Now in this ancient earth-cave I am lost and oppressed—

the valleys are dark, the hills strange, wild, immense,

and this cruel-briared enclosure—an arid abode!

Now the injustice assails me—my lord's absence!

Elsewhere on earth lovers share the same bed

while I pass through life dead,

in this dark abscess where I wilt in the heat, unable to rest

or forget the sorrows of my life's hard lot.

A young woman must always be

stern, hard-of-heart, unmoved, full of belief,

enduring breast-cares, suppressing her own feelings.

She must appear cheerful

even in a tumult of grief.

Now, like a criminal exiled to a far-off land,

moaning beneath insurmountable cliffs,

my weary-minded love, drenched by wild storms

and caught in the clutches of anguish, mourns,

reminded constantly of our former happiness.

Woe be it to them who abide in longing.

envoyé par Bernart Bartleby - 8/7/2014 - 22:52

Langue: anglais

Traduzione inglese moderna di Richard Hamer (2002)

Modern English translation by Richard Hamer (2002)

Modern English translation by Richard Hamer (2002)

THE WIFE'S LAMENT

I sing this song about myself, full sad,

My own distress, and tell what hardships I

Have had to suffer since I first grew up,

Present and past, but never more than now;

I ever suffered grief through banishment.

For since my lord departed from this people

Over the sea, each dawn have I had care

Wondering where my lord may be on land.

When I set off to join and serve my lord,

A friendless exile in my sorry plight,

My husband's kinsmen plotted secretly

How they might separate us from each other

That we might live in wretchedness apart

Most widely in the world: and my heart longed.

In the first place my lord had ordered me

To take up my abode here, though I had

Among these people few dear loyal friends;

Therefore my heart is sad. Then had I found

A fitting man, but one ill-starred, distressed,

Whose hiding heart was contemplating crime,

Though cheerful his demeanour. We had vowed

Full many a time that nought should come between us

But death alone, and nothing else at all.

All that has changed, and it is now as though

Our marriage and our love had never been,

And far or near forever I must suffer

The feud of my beloved husband dear.

So in this forest grove they made me dwell,

Under the oak-tree, in this earthy barrow.

Old is this earth-cave, all I do is yearn.

The dales are dark with high hills up above,

Sharp hedge surrounds it, overgrown with briars,

And joyless is the place. Full often here

The absence of my lord comes sharply to me.

Dear lovers in this world lie in their beds,

While I alone at crack of dawn must walk

Under the oak-tree round this earthy cave,

Where I must stay the length of summer days,

Where I may weep my banishment and all

My many hardships, for I never can

Contrive to set at rest my careworn heart,

Nor all the longing that this life has brought me.

A young man always must be serious,

And tough his character; likewise he should

Seem cheerful, even though his heart is sad

With multitude of cares. All earthly joy

Must come from his own self. Since my dear lord

Is outcast, far off in a distant land,

Frozen by storms beneath a stormy cliff

And dwelling in some desolate abode

Beside the sea, my weary-hearted lord

Must suffer pitiless anxiety.

And all too often he will call to mind

A happier dwelling. Grief must always be

For him who yearning longs for his beloved.

I sing this song about myself, full sad,

My own distress, and tell what hardships I

Have had to suffer since I first grew up,

Present and past, but never more than now;

I ever suffered grief through banishment.

For since my lord departed from this people

Over the sea, each dawn have I had care

Wondering where my lord may be on land.

When I set off to join and serve my lord,

A friendless exile in my sorry plight,

My husband's kinsmen plotted secretly

How they might separate us from each other

That we might live in wretchedness apart

Most widely in the world: and my heart longed.

In the first place my lord had ordered me

To take up my abode here, though I had

Among these people few dear loyal friends;

Therefore my heart is sad. Then had I found

A fitting man, but one ill-starred, distressed,

Whose hiding heart was contemplating crime,

Though cheerful his demeanour. We had vowed

Full many a time that nought should come between us

But death alone, and nothing else at all.

All that has changed, and it is now as though

Our marriage and our love had never been,

And far or near forever I must suffer

The feud of my beloved husband dear.

So in this forest grove they made me dwell,

Under the oak-tree, in this earthy barrow.

Old is this earth-cave, all I do is yearn.

The dales are dark with high hills up above,

Sharp hedge surrounds it, overgrown with briars,

And joyless is the place. Full often here

The absence of my lord comes sharply to me.

Dear lovers in this world lie in their beds,

While I alone at crack of dawn must walk

Under the oak-tree round this earthy cave,

Where I must stay the length of summer days,

Where I may weep my banishment and all

My many hardships, for I never can

Contrive to set at rest my careworn heart,

Nor all the longing that this life has brought me.

A young man always must be serious,

And tough his character; likewise he should

Seem cheerful, even though his heart is sad

With multitude of cares. All earthly joy

Must come from his own self. Since my dear lord

Is outcast, far off in a distant land,

Frozen by storms beneath a stormy cliff

And dwelling in some desolate abode

Beside the sea, my weary-hearted lord

Must suffer pitiless anxiety.

And all too often he will call to mind

A happier dwelling. Grief must always be

For him who yearning longs for his beloved.

envoyé par Riccardo Venturi - 2/11/2014 - 17:24

Langue: italien

"Il lamento della sposa" - Il Wife's Lament toscano, noto anche come I' pan pentito

Nota. Quando Bernart Bartleby non aveva ancora trovato una traduzione italiana del venerabile Wife's Lament della poesia anglosassone, aveva proposto come "corrispettivo" questo popolare canto toscano (che qui ascoltiamo nella prosperosa interpretazione di Ginevra Di Marco). "Corrispettivi" del genere si trovano in tutte le tradizioni popolari (si pensi alla "maumariée" francese); naturalmente, però, un paragone reale col componimento anglosassone non è minimamente possibile. Se paragone vi può essere, è casomai con antiche ballate della tradizione britannica, come ad esempio Childe Waters. [RV]

Nota. Quando Bernart Bartleby non aveva ancora trovato una traduzione italiana del venerabile Wife's Lament della poesia anglosassone, aveva proposto come "corrispettivo" questo popolare canto toscano (che qui ascoltiamo nella prosperosa interpretazione di Ginevra Di Marco). "Corrispettivi" del genere si trovano in tutte le tradizioni popolari (si pensi alla "maumariée" francese); naturalmente, però, un paragone reale col componimento anglosassone non è minimamente possibile. Se paragone vi può essere, è casomai con antiche ballate della tradizione britannica, come ad esempio Childe Waters. [RV]

IL LAMENTO DELLA SPOSA

Aveo le fibbie belle

aveo de be' vestiti

ora mi so' spariti in su i' momento

l'orologio d'argento

e' ci tenevo appesa

una bella catenina ciondoloni

io gli feci i calzoni

calzette e sottoveste

e giubba delle feste e un be' cappello

credeva d'esse bello

con tutto i' suo ballare

a me tocca stentare poverina!

la sera e la mattina

mi trovo disperata

ho fatto la frittata e me credete

fui messa nella rete

dalla mi' zia Simona

e dalla baccellona della Nena

preso che l'ebbi appena

questo tristo marito

mangiare i' pan pentito a me conviene

credevo di stà bene

e pe' fammi dispetto

e' m'ha venduto i' letto e i' cassettone.

Ragazze belle e bone

da me tutte imparate

zitelle e maritate a avé giudizio

s'entra in un precipizio

appena fatte spose

e so dell'altre cose e 'un le vò dire

con questo vò finire

e non vò anda più 'n là

polenta e baccalà l'è un boccon bono.

Aveo le fibbie belle

aveo de be' vestiti

ora mi so' spariti in su i' momento

l'orologio d'argento

e' ci tenevo appesa

una bella catenina ciondoloni

io gli feci i calzoni

calzette e sottoveste

e giubba delle feste e un be' cappello

credeva d'esse bello

con tutto i' suo ballare

a me tocca stentare poverina!

la sera e la mattina

mi trovo disperata

ho fatto la frittata e me credete

fui messa nella rete

dalla mi' zia Simona

e dalla baccellona della Nena

preso che l'ebbi appena

questo tristo marito

mangiare i' pan pentito a me conviene

credevo di stà bene

e pe' fammi dispetto

e' m'ha venduto i' letto e i' cassettone.

Ragazze belle e bone

da me tutte imparate

zitelle e maritate a avé giudizio

s'entra in un precipizio

appena fatte spose

e so dell'altre cose e 'un le vò dire

con questo vò finire

e non vò anda più 'n là

polenta e baccalà l'è un boccon bono.

envoyé par Bernart Bartleby + CCG/AWS Staff - 2/11/2014 - 17:32

"Il lamento della sposa" toscano fu interpretato anche da Daisy Lumini nel suo disco intitolato "Daisy come Folklore - Daisy Lumini canta la vecchia Toscana" inciso nel 1969 e pubblicato nel 1972.

Bernart Bartleby - 29/3/2016 - 11:30

×

![]()

Versi in inglese antico (anglosassone) di anonimo autore, una delle opere poetiche presenti - insieme a Wulf ond Ēadwacer [Wulf and Eadwacer] - nel manoscritto detto di Exeter (o “Codex Exoniensis”), perchè conservato nella biblioteca della cattedrale di Exeter, nel Devon, uno dei più antichi documenti della produzione poetica in anglosassone. il testo viene qui proposto prima in alcune edizioni critiche a stampa, accompagnato dalla trascrizione così come compare nel manoscritto originale, tratta dalla Wife's Lament Page.

Un lamento che condivide il tema centrale di “Wulf and Eadwacer”, quello della condanna da parte di una donna della società anglosassone, tribale e violenta, dove i più deboli, e tra loro in particolare le donne - serve, madri e spose, merce di scambio per concludere paci ed alleanze, quando andava bene, prede e bottino di guerra, quando andava male - erano in balìa delle scelte e dei capricci degli uomini, delle faide e delle guerre tra i clan.

In questo lamento la protagonista racconta il suo doloroso percorso di vita: perde tutto una prima volta, quando il suo “signore” abbandona il clan, o ne viene allontanato, e lei rimane da sola, invisa ai parenti di lui, che la costringono ad andarsene altrove. Trovatasi in un terra straniera, senza mezzi e senza amici, non le sembra vero di trovare un altro “padrone” che la protegga, ma costui si rivela presto essere un uomo crudele e sanguinario, che non la ama e non si interessa minimamente alla sposa cui ha giurato eterna fedeltà... Così il nuovo matrimonio fallisce ben presto e a lei non resta che il disprezzo per quell’uomo brutale e violento. E di nuovo il clan, i parenti di lui, la allontanano e la costringono a vivere in una grotta o forse addirittura la malcapitata muore, ricordando con nostalgia i brevi momenti di felicità avuti col primo sposo...