Shout the message to the breezes,

Far and wide and to each neighbor,

Hail the voice and soul of labor,

Hail our industrial union.

Rally comrades, arise and forward.

On the morrow we shall see

Bread and roses, song and laughter,

Won by solidarity.

On the march to gain our freedom,

We proclaim the faith that's in us.

Faith and fortitude shall win us

Labor's fight for liberty.

Rally comrades, arise and forward.

On the morrow we shall see

Bread and roses, song and laughter,

Won by solidarity.

Workers join us from all races,

Ever hoping, marching, fighting.

We've unfurled the flag uniting

With us all humanity.

Rally comrades, arise and forward.

On the morrow we shall see

Bread and roses, song and laughter,

Won by solidarity.

Far and wide and to each neighbor,

Hail the voice and soul of labor,

Hail our industrial union.

Rally comrades, arise and forward.

On the morrow we shall see

Bread and roses, song and laughter,

Won by solidarity.

On the march to gain our freedom,

We proclaim the faith that's in us.

Faith and fortitude shall win us

Labor's fight for liberty.

Rally comrades, arise and forward.

On the morrow we shall see

Bread and roses, song and laughter,

Won by solidarity.

Workers join us from all races,

Ever hoping, marching, fighting.

We've unfurled the flag uniting

With us all humanity.

Rally comrades, arise and forward.

On the morrow we shall see

Bread and roses, song and laughter,

Won by solidarity.

envoyé par Bernart Bartleby - 22/5/2014 - 21:29

Langue: italien

Traduzione italiana di Riccardo Venturi

24 aprile 2015

24 aprile 2015

IL PANE E LE ROSE

Gridate il messaggio al vento,

da ogni parte e a chi vi è vicino,

evviva la voce e l'anima del lavoro,

evviva il nostro sindacato industriale.

Compagni, unitevi, insorgete,

promuovete; e all'indomani vedremo

il pane e le rose, il canto e il riso

ottenuti con la solidarietà.

In marcia per avere la nostra libertà

proclamiamo la fede che è in noi.

La fede e la forza ci faranno vincere

la battaglia del lavoro per la libertà

Compagni, unitevi, insorgete,

promuovete; e all'indomani vedremo

il pane e le rose, il canto e il riso

ottenuti con la solidarietà.

Unitevi a noi, lavoratori di tutte le razze

sempre sperando, marciando, lottando.

Abbiamo spiegato la bandiera

che ci unisce all'umanità intera.

Compagni, unitevi, insorgete,

promuovete; e all'indomani vedremo

il pane e le rose, il canto e il riso

ottenuti con la solidarietà.

Gridate il messaggio al vento,

da ogni parte e a chi vi è vicino,

evviva la voce e l'anima del lavoro,

evviva il nostro sindacato industriale.

Compagni, unitevi, insorgete,

promuovete; e all'indomani vedremo

il pane e le rose, il canto e il riso

ottenuti con la solidarietà.

In marcia per avere la nostra libertà

proclamiamo la fede che è in noi.

La fede e la forza ci faranno vincere

la battaglia del lavoro per la libertà

Compagni, unitevi, insorgete,

promuovete; e all'indomani vedremo

il pane e le rose, il canto e il riso

ottenuti con la solidarietà.

Unitevi a noi, lavoratori di tutte le razze

sempre sperando, marciando, lottando.

Abbiamo spiegato la bandiera

che ci unisce all'umanità intera.

Compagni, unitevi, insorgete,

promuovete; e all'indomani vedremo

il pane e le rose, il canto e il riso

ottenuti con la solidarietà.

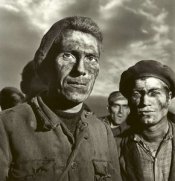

Lawrence, Massachusetts, 1912.

Testimonianza di Camilla Teoli davanti ad una commissione d'inchiesta del Congresso, istituita subito dopo il grande sciopero dei tessili.

Camilla Teoli, di famiglia immigrata dalla'Italia, fu mandata a lavorare prima dei 14 anni, per una paga da fame. Subì un grave incidente, con conseguente ricovero ospedaliero durato mesi, durante il quale non percepì nessun stipendio o indennità.

Partecipò allo sciopero "perchè a casa non c'era abbastanza da mangiare"...

(fonte: "Rebel Voices: An I.W.W. Anthology", a cura di Ann Arbor, University of Michigan Press, 1964)

Testimonianza di Camilla Teoli davanti ad una commissione d'inchiesta del Congresso, istituita subito dopo il grande sciopero dei tessili.

Camilla Teoli, di famiglia immigrata dalla'Italia, fu mandata a lavorare prima dei 14 anni, per una paga da fame. Subì un grave incidente, con conseguente ricovero ospedaliero durato mesi, durante il quale non percepì nessun stipendio o indennità.

Partecipò allo sciopero "perchè a casa non c'era abbastanza da mangiare"...

(fonte: "Rebel Voices: An I.W.W. Anthology", a cura di Ann Arbor, University of Michigan Press, 1964)

CHAIRMAN. Camella, how old are you?

Miss TEOLI. Fourteen years and eight months.

CHAIRMAN. Fourteen years and eight months?

Miss TEOLI. Yes.

CHAIRMAN. How many children are there in your family?

Miss TEOLI. Five.

CHAIRMAN. Where do you work?

Miss TEOLI. In the woolen mill.

CHAIRMAN. For the American Woolen Co.?

Miss TEOLI. Yes.

CHAIRMAN. What sort of work do you do?

Miss TEOLI. Twisting.

CHAIRMAN. You do twisting?

Miss TEOLI. Yes.

CHAIRMAN. How much do you get a week?

Miss TEOLI. $6.55.

CHAIRMAN. What is the smallest pay?

Miss TEOLI. $2.64.

CHAIRMAN. Do you have to pay anything for water?

Miss TEOLI. Yes.

CHAIRMAN. How much?

Miss TEOLI. 10 cents every two weeks.

CHAIRMAN. Do they hold back any of your pay?

Miss TEOLI. No.

CHAIRMAN. Have they ever held back any?

Miss TEOLI. One week’s pay.

CHAIRMAN. They have held back one week’s pay?

Miss TEOLI. Yes.

CHAIRMAN. Does your father work, and where?

Miss TEOLI. My father works in the Washington.

CHAIRMAN. The Washington Woolen Mill?

Miss TEOLI. Yes, sir.

CHAIRMAN. How much pay does he get for a week’s work?

Miss TEOLI. $7.70

CHAIRMAN. Does he always work a full week?

Miss TEOLI. No.

CHAIRMAN. Well, how often does it happen that he does not work a full week?

Miss TEOLI. He works in the winter a full week, and usually he don’t in the summer.

CHAIRMAN. In the winter he works a full week, and in the summer how much?

Miss TEOLI. Two or three days a week.

CHAIRMAN. What sort of work does he do?

Miss TEOLI. He is a comber.

CHAIRMAN. Now, did you ever get hurt in the mill?

Miss TEOLI. Yes.

CHAIRMAN. Can you tell the committee about that — how it happened and what it was?

Miss TEOLI. Yes.

CHAIRMAN. Tell us about it now, in your own way.

Miss TEOLI. Well, I used to go to school, and then a man came up to my house and asked my father why I didn’t go to work, so my father says I don’t know whether she is 13 or 14 years old. So, the man say you give me $4 and I will make the papers come from the old country saying you are 14. So, my father gave him the $4, and in one month came the papers that I was 14. I went to work, and about two weeks got hurt in my head.

CHAIRMAN. Now, how did you get hurt, and where were you hurt in the head; explain that to the committee?

Miss TEOLI. I got hurt in Washington.

CHAIRMAN. In the Washington Mill?

Miss TEOLI. Yes, sir.

CHAIRMAN. What part of your head?

Miss TEOLI. My head.

CHAIRMAN. Well, how were you hurt?

Miss TEOLI. The machine pulled the scalp off.

CHAIRMAN. The machine pulled your scalp off?

Miss TEOLI. Yes, sir.

CHAIRMAN. How long ago was that?

Miss TEOLI. A year ago, or about a year ago.

CHAIRMAN. Were you in the hospital after that?

Miss TEOLI. I was in the hospital seven months.

CHAIRMAN. Seven months?

Miss TEOLI. Yes.

CHAIRMAN. Did the company pay your bills while you were in the hospital?

Miss TEOLI. Yes, sir.

CHAIRMAN. The company took care of you?

Miss TEOLI. The company only paid my bills; they didn’t give me anything else.

CHAIRMAN. They only paid your hospital bills; they did not give you any pay?

Miss TEOLI. No, sir.

CHAIRMAN. But paid the doctors bills and hospital fees?

Miss TEOLI. Yes, sir.

Mr. LENROOT. They did not pay your wages?

Miss TEOLI. No, sir.

CHAIRMAN. Did they arrest your father for having sent you to work for 14?

Miss TEOLI. Yes, sir.

CHAIRMAN. What did they do with him after they arrested him?

Miss TEOLI. My father told this about the man he gave $4 to, and then they put him on again.

CHAIRMAN. Are you still being treated by the doctors for the scalp wound?

Miss TEOLI. Yes, sir.

CHAIRMAN. How much longer do they tell you, you will have to be treated?

Miss TEOLI. They don’t know.

CHAIRMAN. They do not know?

Miss TEOLI. No.

CHAIRMAN. Are you working now?

Miss TEOLI. Yes, sir.

CHAIRMAN. How much are you getting?

Miss TEOLI. $6.55.

CHAIRMAN. Are you working in the same place where you were before you were hurt?

Miss TEOLI. No.

CHAIRMAN. In another mill?

Miss TEOLI. Yes.

CHAIRMAN. What mill?

Miss TEOLI. The Wood Mill.

CHAIRMAN. The what?

Miss TEOLI. The Wood Mill.

CHAIRMAN. Were you down at the station on Saturday, the 24th of February?

Miss TEOLI. I work in a town in Massachusetts, and I don’t know nothing about that.

CHAIRMAN. You do not know anything about that?

Miss TEOLI. No, sir.

CHAIRMAN. How long did you go to school?

Miss TEOLI. I left when I was in the sixth grade.

CHAIRMAN. You left when you were in the sixth grade?

Miss TEOLI. Yes, sir.

CHAIRMAN. And you have been working ever since, except while you were in the hospital?

Miss TEOLI. Yes, sir.

Mr. CAMPBELL. Do you know the man who came to your father and offered to get a certificate that you were 14 years of age?

Miss TEOLI. I know the man, but I have forgot him now.

Mr. CAMPBELL. You know him, but you do not remember his name now?

Miss TEOLI. Yes.

Mr. CAMPBELL. Do you know what he did; what his work was?

Miss TEOLI. No.

Mr. CAMPBELL. Was he connected with any of the mills?

Miss TEOLI. I don’t know.

Mr. CAMPBELL. Is he an Italian?

Miss TEOLI. Yes, sir.

Mr. CAMPBELL. He knew your father well?

Miss TEOLI. Yes, sir.

Mr. CAMPBELL. Was he a friend of your father?

Miss TEOLI. No.

Mr. CAMPBELL. Did he ever come about your house visiting there?

Miss TEOLI. I don’t know.

Mr. CAMPBELL. I mean before he asked about your going to work in the mills?

Miss TEOLI. Yes, sir.

Mr. CAMPBELL. He used to come to your house and was a friend of the family?

Miss TEOLI. Yes.

Mr. CAMPBELL. You are sure he was not connected or employed by some of the mills?

Miss TEOLI. I don’t know, I don’t think so.

Mr. CAMPBELL. Do they go around in Lawrence there and find little girls and boys in the schools over 14 years of age and urge them to quit school and go to work in the mills?

Miss TEOLI. I don’t know.

Mr. CAMPBELL. You don’t know anything about that?

Miss TEOLI. No.

Mr. CAMPBELL. Do you know of any little girls besides yourself, who were asked to go to work as soon as they were 14?

Miss TEOLI. No, I don t know; no.

Mr. HARDWICK. Are you one of the strikers?

Miss TEOLI. Yes, sir.

Mr. HARDWICK. Did you agree to the strike before it was ordered; did they ask you anything about striking before you quit?

Miss TEOLI. No.

Mr. HARDWICK. But you joined them after they quit?

Miss TEOLI. Yes.

Mr. HARDWICK. Why did you do that?

Miss TEOLI. Because I didn’t get enough to eat at home.

Mr. HARDWICK. You did not get enough to eat at home?

Miss TEOLI. No.

Mr. HARDWICK. Why didn’t you propose a strike yourself, then?

Miss TEOLI. I did.

Mr. HARDWICK. I thought you said you did not know anything about the strike until after it started. How about that? Did you know there was going to be a strike before they did strike?

Miss TEOLI. No.

Mr. HARDWICK. They did not consult with you about that?

Miss TEOLI. No.

Mr. HARDWICK. You did not agree to strike?

Miss TEOLI. No.

Mr. HARDWICK. You were not a party to it, to begin with?

Miss TEOLI. No.

Mr. HARDWICK. Was not the reason you went into it because you were afraid to go on with your work?

Miss TEOLI. Yes.

Mr. HARDWICK. You say that was the reason?

Miss TEOLI. Yes.

Mr. HARDWICK. Now, did you see any of the occurrences — any of the riots during this strike?

Miss TEOLI. No.

Mr. HARDWICK. You did not see any of the women beaten, or anything like that?

Miss TEOLI. No.

Mr. HARDWICK. You did not see anybody hurt or beaten or killed, or anything like that?

Miss TEOLI. No.

Mr. HARDWICK. Did you come down to the depot with the children who were trying to go away?

Miss TEOLI. I am only in the town in Massachusetts, and I don’t come down to the city.

Mr. HARDWICK. So you did not see any of that?

Miss TEOLI. No.

Mr. HARDWICK. You do not know anything about those things at all?

Miss TEOLI. No.

Mr. HARDWICK. You struck after the balance had struck and were afraid to go on with your work?

Miss TEOLI. Yes.

Mr. LENROOT. There is a high school in Lawrence, isn’t there?

Miss TEOLI. Yes, sir.

Mr. LENROOT. And some of your friends—boys and girls—go to the high school?

Miss TEOLI. I don’t know.

Mr. LENROOT. None that you know are going to the high school?

Miss TEOLI. No.

Miss TEOLI. Fourteen years and eight months.

CHAIRMAN. Fourteen years and eight months?

Miss TEOLI. Yes.

CHAIRMAN. How many children are there in your family?

Miss TEOLI. Five.

CHAIRMAN. Where do you work?

Miss TEOLI. In the woolen mill.

CHAIRMAN. For the American Woolen Co.?

Miss TEOLI. Yes.

CHAIRMAN. What sort of work do you do?

Miss TEOLI. Twisting.

CHAIRMAN. You do twisting?

Miss TEOLI. Yes.

CHAIRMAN. How much do you get a week?

Miss TEOLI. $6.55.

CHAIRMAN. What is the smallest pay?

Miss TEOLI. $2.64.

CHAIRMAN. Do you have to pay anything for water?

Miss TEOLI. Yes.

CHAIRMAN. How much?

Miss TEOLI. 10 cents every two weeks.

CHAIRMAN. Do they hold back any of your pay?

Miss TEOLI. No.

CHAIRMAN. Have they ever held back any?

Miss TEOLI. One week’s pay.

CHAIRMAN. They have held back one week’s pay?

Miss TEOLI. Yes.

CHAIRMAN. Does your father work, and where?

Miss TEOLI. My father works in the Washington.

CHAIRMAN. The Washington Woolen Mill?

Miss TEOLI. Yes, sir.

CHAIRMAN. How much pay does he get for a week’s work?

Miss TEOLI. $7.70

CHAIRMAN. Does he always work a full week?

Miss TEOLI. No.

CHAIRMAN. Well, how often does it happen that he does not work a full week?

Miss TEOLI. He works in the winter a full week, and usually he don’t in the summer.

CHAIRMAN. In the winter he works a full week, and in the summer how much?

Miss TEOLI. Two or three days a week.

CHAIRMAN. What sort of work does he do?

Miss TEOLI. He is a comber.

CHAIRMAN. Now, did you ever get hurt in the mill?

Miss TEOLI. Yes.

CHAIRMAN. Can you tell the committee about that — how it happened and what it was?

Miss TEOLI. Yes.

CHAIRMAN. Tell us about it now, in your own way.

Miss TEOLI. Well, I used to go to school, and then a man came up to my house and asked my father why I didn’t go to work, so my father says I don’t know whether she is 13 or 14 years old. So, the man say you give me $4 and I will make the papers come from the old country saying you are 14. So, my father gave him the $4, and in one month came the papers that I was 14. I went to work, and about two weeks got hurt in my head.

CHAIRMAN. Now, how did you get hurt, and where were you hurt in the head; explain that to the committee?

Miss TEOLI. I got hurt in Washington.

CHAIRMAN. In the Washington Mill?

Miss TEOLI. Yes, sir.

CHAIRMAN. What part of your head?

Miss TEOLI. My head.

CHAIRMAN. Well, how were you hurt?

Miss TEOLI. The machine pulled the scalp off.

CHAIRMAN. The machine pulled your scalp off?

Miss TEOLI. Yes, sir.

CHAIRMAN. How long ago was that?

Miss TEOLI. A year ago, or about a year ago.

CHAIRMAN. Were you in the hospital after that?

Miss TEOLI. I was in the hospital seven months.

CHAIRMAN. Seven months?

Miss TEOLI. Yes.

CHAIRMAN. Did the company pay your bills while you were in the hospital?

Miss TEOLI. Yes, sir.

CHAIRMAN. The company took care of you?

Miss TEOLI. The company only paid my bills; they didn’t give me anything else.

CHAIRMAN. They only paid your hospital bills; they did not give you any pay?

Miss TEOLI. No, sir.

CHAIRMAN. But paid the doctors bills and hospital fees?

Miss TEOLI. Yes, sir.

Mr. LENROOT. They did not pay your wages?

Miss TEOLI. No, sir.

CHAIRMAN. Did they arrest your father for having sent you to work for 14?

Miss TEOLI. Yes, sir.

CHAIRMAN. What did they do with him after they arrested him?

Miss TEOLI. My father told this about the man he gave $4 to, and then they put him on again.

CHAIRMAN. Are you still being treated by the doctors for the scalp wound?

Miss TEOLI. Yes, sir.

CHAIRMAN. How much longer do they tell you, you will have to be treated?

Miss TEOLI. They don’t know.

CHAIRMAN. They do not know?

Miss TEOLI. No.

CHAIRMAN. Are you working now?

Miss TEOLI. Yes, sir.

CHAIRMAN. How much are you getting?

Miss TEOLI. $6.55.

CHAIRMAN. Are you working in the same place where you were before you were hurt?

Miss TEOLI. No.

CHAIRMAN. In another mill?

Miss TEOLI. Yes.

CHAIRMAN. What mill?

Miss TEOLI. The Wood Mill.

CHAIRMAN. The what?

Miss TEOLI. The Wood Mill.

CHAIRMAN. Were you down at the station on Saturday, the 24th of February?

Miss TEOLI. I work in a town in Massachusetts, and I don’t know nothing about that.

CHAIRMAN. You do not know anything about that?

Miss TEOLI. No, sir.

CHAIRMAN. How long did you go to school?

Miss TEOLI. I left when I was in the sixth grade.

CHAIRMAN. You left when you were in the sixth grade?

Miss TEOLI. Yes, sir.

CHAIRMAN. And you have been working ever since, except while you were in the hospital?

Miss TEOLI. Yes, sir.

Mr. CAMPBELL. Do you know the man who came to your father and offered to get a certificate that you were 14 years of age?

Miss TEOLI. I know the man, but I have forgot him now.

Mr. CAMPBELL. You know him, but you do not remember his name now?

Miss TEOLI. Yes.

Mr. CAMPBELL. Do you know what he did; what his work was?

Miss TEOLI. No.

Mr. CAMPBELL. Was he connected with any of the mills?

Miss TEOLI. I don’t know.

Mr. CAMPBELL. Is he an Italian?

Miss TEOLI. Yes, sir.

Mr. CAMPBELL. He knew your father well?

Miss TEOLI. Yes, sir.

Mr. CAMPBELL. Was he a friend of your father?

Miss TEOLI. No.

Mr. CAMPBELL. Did he ever come about your house visiting there?

Miss TEOLI. I don’t know.

Mr. CAMPBELL. I mean before he asked about your going to work in the mills?

Miss TEOLI. Yes, sir.

Mr. CAMPBELL. He used to come to your house and was a friend of the family?

Miss TEOLI. Yes.

Mr. CAMPBELL. You are sure he was not connected or employed by some of the mills?

Miss TEOLI. I don’t know, I don’t think so.

Mr. CAMPBELL. Do they go around in Lawrence there and find little girls and boys in the schools over 14 years of age and urge them to quit school and go to work in the mills?

Miss TEOLI. I don’t know.

Mr. CAMPBELL. You don’t know anything about that?

Miss TEOLI. No.

Mr. CAMPBELL. Do you know of any little girls besides yourself, who were asked to go to work as soon as they were 14?

Miss TEOLI. No, I don t know; no.

Mr. HARDWICK. Are you one of the strikers?

Miss TEOLI. Yes, sir.

Mr. HARDWICK. Did you agree to the strike before it was ordered; did they ask you anything about striking before you quit?

Miss TEOLI. No.

Mr. HARDWICK. But you joined them after they quit?

Miss TEOLI. Yes.

Mr. HARDWICK. Why did you do that?

Miss TEOLI. Because I didn’t get enough to eat at home.

Mr. HARDWICK. You did not get enough to eat at home?

Miss TEOLI. No.

Mr. HARDWICK. Why didn’t you propose a strike yourself, then?

Miss TEOLI. I did.

Mr. HARDWICK. I thought you said you did not know anything about the strike until after it started. How about that? Did you know there was going to be a strike before they did strike?

Miss TEOLI. No.

Mr. HARDWICK. They did not consult with you about that?

Miss TEOLI. No.

Mr. HARDWICK. You did not agree to strike?

Miss TEOLI. No.

Mr. HARDWICK. You were not a party to it, to begin with?

Miss TEOLI. No.

Mr. HARDWICK. Was not the reason you went into it because you were afraid to go on with your work?

Miss TEOLI. Yes.

Mr. HARDWICK. You say that was the reason?

Miss TEOLI. Yes.

Mr. HARDWICK. Now, did you see any of the occurrences — any of the riots during this strike?

Miss TEOLI. No.

Mr. HARDWICK. You did not see any of the women beaten, or anything like that?

Miss TEOLI. No.

Mr. HARDWICK. You did not see anybody hurt or beaten or killed, or anything like that?

Miss TEOLI. No.

Mr. HARDWICK. Did you come down to the depot with the children who were trying to go away?

Miss TEOLI. I am only in the town in Massachusetts, and I don’t come down to the city.

Mr. HARDWICK. So you did not see any of that?

Miss TEOLI. No.

Mr. HARDWICK. You do not know anything about those things at all?

Miss TEOLI. No.

Mr. HARDWICK. You struck after the balance had struck and were afraid to go on with your work?

Miss TEOLI. Yes.

Mr. LENROOT. There is a high school in Lawrence, isn’t there?

Miss TEOLI. Yes, sir.

Mr. LENROOT. And some of your friends—boys and girls—go to the high school?

Miss TEOLI. I don’t know.

Mr. LENROOT. None that you know are going to the high school?

Miss TEOLI. No.

Bernart Bartleby - 23/4/2015 - 12:54

Sarebbe interessante andare a vedere la clamorosa fortuna che l'espressione "Bread and Roses" ha avuto praticamente fino ai giorni nostri, e in tutto il mondo. Basterebbe ricordare che, negli anni '70, un'intera e famosa collana di libri dell'editore Savelli (Giulio Savelli, allora editore della sinistra extraparlamentare poi passato armi e bagagli a Forza Italia e alla Lega) era intitolata "Il pane e le rose" (era quella, tra le altre cose, di "Porci con le ali, diario sessuo-politico di due adolescenti"). Oppure Gilbert Bécaud che, nel 1967, proclamando il suo disimpegno alla vigilia di certi avvenimenti, cantava "L'important, c'est la rose" (del pane si può fare a meno). Ma si potrebbe andare avanti per paginate intere, anche se è meglio -a mio parere- attenersi agli avvenimenti del 1912.

Riccardo Venturi - 24/4/2015 - 08:54

×

![]()

Versi di Arturo Giovannitti, (1884-1959), molisano emigrato negli USA, dove divenne sindacalista socialista, dirigente dell’IWW (Industrial Workers of the World) e poeta e dove fu amico di Carlo Tresca, di Nicola Sacco e di Bartolomeo Vanzetti.

Musica attribuita a Giuseppe Adami (1878-1946), che però fu scrittore, commediografo e librettista, non musicista.

Su Political Folk Music, il sito dove ho reperito il testo, si afferma che la poesia sarebbe stata tradotta in inglese da tal Samuel H. Friedman: credo non sia corretto, perchè Arturo Giovannitti era perfettamente bilingue, con ottima padronanza sia della lingua d’origine che di quella acquisita. Inoltre, la poesia in questione deve essere stata composta nell’immediatezza dei fatti di Lawrence del 1912 (“The Bread and Roses Strike”), quando Giovannitti era già un apprezzato dirigente dell’IWW e quindi si rivolgeva direttamente ai lavoratori americani.

Il 19 gennaio 1912, a Lawrence, centro tessile del Massachusetts, fu organizzato uno sciopero della classe operaia contro le multinazionali, che passò alla storia con il nome di "Sciopero del Pane e delle Rose".

Durante lo sciopero, in uno scontro con le forze dell'ordine rimase uccisa una ragazza, Anna Lopizzo, giovane operaia tessile.

Joseph Caruso, scioperante non ancora aderente al sindacato, ed i due dirigenti “wobblies” Joseph “Giuseppe” Ettor e Arturo Giovannitti, vennero accusati dell'omicidio della ragazza, con un procedimento del tutto simile a quelli con cui, pochi anni dopo, verranno eliminati il sindacalista e musicista di origine svedese Joe Hill (Joseph Hillstrom) ed i due anarchici di origine italiana Sacco e Vanzetti.

I tre di Lawrence furono incarcerati ed il loro caso suscitò vaste reazioni nell'opinione pubblica americana, e non solo. Per affermare la loro innocenza, si mobilitarono comitati e associazioni in tutto il mondo, in una campagna di solidarietà internazionale che, tra l'altro, vide nel settembre 1912 a Berna (Svizzera) la partecipazione di operai italiani, alcuni dei quali pure arrestati.

L'IWW aprì una sottoscrizione per pagare le spese legali dei tre wobblies. I lavoratori tessili di Lawrence proclamarono uno sciopero generale di solidarietà per il loro rilascio.

Il processo si svolse a Salem, nel Massachusetts: dopo cinque mesi di carcerazione, gli imputati furono scagionati nel novembre del 1912.

Allo scoppio della prima guerra mondiale, il sindacato IWW si dichiarò contro la guerra. E nel 1917, dopo l'entrata in guerra degli Stati Uniti (e dopo la vittoria della Rivoluzione russa), contro il sindacato si scatenò la violenza sciovinista. Le sedi dei Wobblies furono distrutte dalla polizia, i militanti linciati, picchiati, incarcerati a centinaia. Migliaia di simpatizzanti furono processati e finirono in carcere, centinaia furono deportati. La stampa di sinistra fu soppressa, censurata o esclusa dalla circolazione. Archivi, corrispondenza, carte e registri dell'IWW furono sequestrati o distrutti. (fonte: it.wikipedia)