It's so relieving to know that you're leaving as soon as you get paid

It's so relaxing to hear you're asking wherever you get your way

It's so soothing to know that you'll sue me, this is starting to sound the same

I miss the comfort in being sad

I miss the comfort in being sad

I miss the comfort in being sad

In her false withness, we hope you're still with us,

To see if they float or drown

Our favorite patient,

A display of patience, disease-covered Puget Sound

She'll come back as fire, to burn all the liars,

And leave a blanket of ash on the ground

I miss the comfort in being sad

I miss the comfort in being sad

I miss the comfort in being sad

It's so relaxing to hear you're asking wherever you get your way

It's so soothing to know that you'll sue me, this is starting to sound the same

I miss the comfort in being sad

I miss the comfort in being sad

I miss the comfort in being sad

In her false withness, we hope you're still with us,

To see if they float or drown

Our favorite patient,

A display of patience, disease-covered Puget Sound

She'll come back as fire, to burn all the liars,

And leave a blanket of ash on the ground

I miss the comfort in being sad

I miss the comfort in being sad

I miss the comfort in being sad

Lingua: Italiano

Traduzione italiana

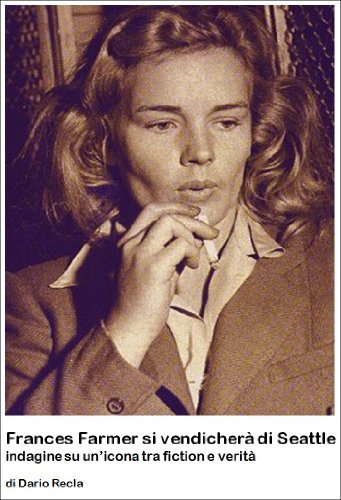

FRANCES FARMER SI VENDICHERÀ SU SEATTLE

È un tale sollievo sapere che te ne andrai non appena sarai pagata

È così rilassante sentirti domandare, dovunque otterrai quel che vuoi

È così confortante sapere che mi citerai in giudizio

sta cominciando a suonare uguale

Mi manca il conforto della tristezza

Mi manca il conforto della tristezza

Mi manca il conforto della tristezza

Nella tua falsa testimonianza, speriamo che tu sia ancora tra noi

Per vedere se affogano o galleggiano

La nostra paziente preferita,

di ostentata pazienza, stretto di Puget (*) ricoperto di malattie

Tornerà come fuoco per bruciare tutti i bugiardi

e lasciare una coltre di cenere sul terreno

Mi manca il conforto della tristezza

Mi manca il conforto della tristezza

Mi manca il conforto della tristezza

È un tale sollievo sapere che te ne andrai non appena sarai pagata

È così rilassante sentirti domandare, dovunque otterrai quel che vuoi

È così confortante sapere che mi citerai in giudizio

sta cominciando a suonare uguale

Mi manca il conforto della tristezza

Mi manca il conforto della tristezza

Mi manca il conforto della tristezza

Nella tua falsa testimonianza, speriamo che tu sia ancora tra noi

Per vedere se affogano o galleggiano

La nostra paziente preferita,

di ostentata pazienza, stretto di Puget (*) ricoperto di malattie

Tornerà come fuoco per bruciare tutti i bugiardi

e lasciare una coltre di cenere sul terreno

Mi manca il conforto della tristezza

Mi manca il conforto della tristezza

Mi manca il conforto della tristezza

(*) Puget Sound (lo Stretto di Puget) è una località vicino a Seattle dove la Farmer fu ricoverata.

Frances Bean prende il nome da Frances Mac Kee dei vaselines. Infatti se fosse stata maschio si sarebbe chiamata Eugene come l’altro componente dei Vaselines.

Frances Farmer - 2/12/2017 - 02:41

"GOD DIES", by Frances Farmer at the age of 18, May 2, 1931

No one ever came to me and said, "You're a fool. There isn't such a thing as God. Somebody's been stuffing you." It wasn't a murder. I think God just died of old age. And when I realized that he wasn't any more, it didn't shock me. It seemed natural and right.

Maybe it was because I was never properly impressed with a religion. I went to Sunday school and liked the stories about Christ and the Christmas star. They were beautiful. They made you warm and happy to think about. But I didn't believe them. The Sunday School teacher talked too much in the way our grade school teacher used to when she told us about George Washington. Pleasant, pretty stories, but not true.

Religion was too vague. God was different. He was something real, something I could feel. But there were only certain times when I could feel it. I used to lie between cool, clean sheets at night after I'd had a bath, after I had washed my hair and scrubbed my knuckles and finger nails and teeth. Then I could lie quite still in the dark with my face to the window with the trees in it, and talk to God. "I am clean, now. I've never been as clean. I'll never be cleaner." And somehow, it was God. I wasn't sure that it was … just something cool and dark and clean.

That wasn't religion, though. There was too much of the physical about it. I couldn't get that same feeling during the day, with my hands in dirty dish water and the hard sun showing up the dirtiness on the roof-tops. And after a time, even at night, the feeling of God didn't last. I began to wonder what the minister meant when he said, "God, the father, sees even the smallest sparrow fall. He watches over all his children." That jumbled it all up for me. But I was sure of one thing. If God were a father, with children, that cleanliness I had been feeling wasn't God. So at night, when I went to bed, I would think, "I am clean. I am sleepy." And then I went to sleep. It didn't keep me from enjoying the cleanness any less. I just knew that God wasn't there. He was a man on a throne in Heaven, so he was easy to forget.

Sometimes I found he was useful to remember; especially when I lost things that were important. After slamming through the house, panicky and breathless from searching, I could stop in the middle of a room and shut my eyes. "Please God, let me find my red hat with the blue trimmings." It usually worked. God became a super-father that couldn't spank me. But if I wanted a thing badly enough, he arranged it.

That satisfied me until I began to figure that if God loved all his children equally, why did he bother about my red hat and let other people lose their fathers and mothers for always? I began to see that he didn't have much to do about hats, people dying or anything. They happened whether he wanted them to or not, and he stayed in heaven and pretended not to notice. I wondered a little why God was such a useless thing. It seemed a waste of time to have him. After that he became less and less, until he was…nothingness.

I felt rather proud to think that I had found the truth myself, without help from any one. It puzzled me that other people hadn't found out, too. God was gone. We were younger. We had reached past him. Why couldn’t they see it? It still puzzles me.

No one ever came to me and said, "You're a fool. There isn't such a thing as God. Somebody's been stuffing you." It wasn't a murder. I think God just died of old age. And when I realized that he wasn't any more, it didn't shock me. It seemed natural and right.

Maybe it was because I was never properly impressed with a religion. I went to Sunday school and liked the stories about Christ and the Christmas star. They were beautiful. They made you warm and happy to think about. But I didn't believe them. The Sunday School teacher talked too much in the way our grade school teacher used to when she told us about George Washington. Pleasant, pretty stories, but not true.

Religion was too vague. God was different. He was something real, something I could feel. But there were only certain times when I could feel it. I used to lie between cool, clean sheets at night after I'd had a bath, after I had washed my hair and scrubbed my knuckles and finger nails and teeth. Then I could lie quite still in the dark with my face to the window with the trees in it, and talk to God. "I am clean, now. I've never been as clean. I'll never be cleaner." And somehow, it was God. I wasn't sure that it was … just something cool and dark and clean.

That wasn't religion, though. There was too much of the physical about it. I couldn't get that same feeling during the day, with my hands in dirty dish water and the hard sun showing up the dirtiness on the roof-tops. And after a time, even at night, the feeling of God didn't last. I began to wonder what the minister meant when he said, "God, the father, sees even the smallest sparrow fall. He watches over all his children." That jumbled it all up for me. But I was sure of one thing. If God were a father, with children, that cleanliness I had been feeling wasn't God. So at night, when I went to bed, I would think, "I am clean. I am sleepy." And then I went to sleep. It didn't keep me from enjoying the cleanness any less. I just knew that God wasn't there. He was a man on a throne in Heaven, so he was easy to forget.

Sometimes I found he was useful to remember; especially when I lost things that were important. After slamming through the house, panicky and breathless from searching, I could stop in the middle of a room and shut my eyes. "Please God, let me find my red hat with the blue trimmings." It usually worked. God became a super-father that couldn't spank me. But if I wanted a thing badly enough, he arranged it.

That satisfied me until I began to figure that if God loved all his children equally, why did he bother about my red hat and let other people lose their fathers and mothers for always? I began to see that he didn't have much to do about hats, people dying or anything. They happened whether he wanted them to or not, and he stayed in heaven and pretended not to notice. I wondered a little why God was such a useless thing. It seemed a waste of time to have him. After that he became less and less, until he was…nothingness.

I felt rather proud to think that I had found the truth myself, without help from any one. It puzzled me that other people hadn't found out, too. God was gone. We were younger. We had reached past him. Why couldn’t they see it? It still puzzles me.

B.B. - 2/12/2017 - 22:14

×

![]()

Vent'anni fa, con un colpo di fucile nella sua casa di Seattle, Kurt Cobain diceva addio a questo mondo. Nella lettera di commiato citava una famosa canzone di Neil Young, "Hey Hey, My My" - "it's better to burn out than to fade away", è meglio bruciarsi in fretta che spegnersi lentamente. E infatti il ragazzo aveva bruciato in fretta tutte le tappe passando dai locali underground di Seattle a scalzare Michael Jackson ai vertici delle classifiche statunitensi, facendo diventare i Nirvana il gruppo simbolo delle inquietudini della generazione di ventenni negli anni '90. Il grunge sapeva mettere insieme la furia del punk con la malinconia del blues e del folk, e Cobain lo dimostrava benissimo quando si esibiva in "Where did you Sleep Last Night", cover di un vecchio pezzo del bluesman Leadbelly.

Ci dispiaceva davvero che in tutte le CCG non ci fosse neanche un pezzo dei Nirvana, ma è difficile trovare nei testi di Cobain esplicite prese di posizioni politiche e sociali, a differenza per esempio dei più impegnati Pearl Jam. Ma questa esplosiva canzone, una delle migliori del gruppo anche se non tra le più famose, dedicata alla triste storia di Frances Bean, merita il suo posto nel percorso sulla "guerra dei manicomi".

Partendo dalla demistificazione di Seattle come luogo perfetto, Cobain sposta l'attenzione sulla presenza di giudici e capi di stato, per lui ancora oggi "seduti nelle loro belle e fottute case", organizzati in una struttura che li vede cospirare contro chi potrebbe risultare pericoloso.

Secondo Cobain molti accusatori si trovano ancora oggi a Seattle e il verso "nella sua falsa testimonianza / Speriamo che tu sia ancora fra noi", si riferisce all'articolo pubblicato dalla Hirschberg su Vanity Fair [che attaccava duramente Cobain e Courtney Love bollati come genitori irresponsabili e eroinomani NdR].

Nel verso "vedere se galleggiano o affogano" tornano le prove per accertarsi della stregoneria di Serve the servants.

Il testo si conclude con un'immagine di riscatto e vendetta personale: "Tornerà come fuoco / per bruciare tutti i bugiardi / e lasciare una coltre di cenere sul terreno".

Le cose che sulla carta potrebbero dare felicità a una persona -successo e ricchezza- si rivelarono nella storia della Farmer come fonti di distruzione. Per analogia, lo stesso successo che lo aveva ormai travolto portò Cobain a un'amara constatazione: l'assenza del conforto dell'essere tristi. Il sottile riferimento personale e la sensazione di un'immedesimazione di Cobain (la stessa tecnica diffamatoria usata per la Farmer la stavano subendo lui e la sua famiglia) si pongono comunque ai margini. Il suo obbiettivo è riportare in vita la storia di Frances Farmer, diffonderla a chi ancora non la conosce, come un avvertimento del tipo "potrebbe capitare anche a te se non stai attento" (sopratutto se consideriamo che la vicenda è abbastanza recente), oltre ovviamente a una denuncia dell'intolleranza e della burocrazia.

tratto da Le canzoni dei Nirvana -commento e traduzione dei testi - Giulio Nannini

*

Ora, bisogna chiedersi: perché Cobain era talmente legato alla Farmer? Fissato a tal punto da chiamare Frances la sua unica figlia, e da far indossare alla Love, nel giorno del loro matrimonio, un vestito verde appartenuto all’attrice. Confrontando le due biografie, i caratteri e le scelte di vita, le risposte vengono fuori. Il leader dei Nirvana ha sempre rifiutato il ruolo di star, di portavoce della Generazione X. Ha sempre reso palese, fin troppo, l’odio e il disgusto per il mondo discografico e gli squali che lo popolano. Sensibile ed emotivo, ha pagato in prima persona la fama e il successo mondiale di Nevermind. Un peso insopportabile e opprimente che, andandosi a legare con i traumi del passato mai del tutto superati e le dipendenze sempre più gravi, ha causato un infausto finale. Francis Farmer è una sorta di modello e di alter ego. Colei che fu tra le prima ad agire senza piegarsi alle regole degli Studios, agendo sempre di testa sua. Anche lei ha pagato a caro prezzo la sua fragilità e la sua purezza, tra il declino rapido e il logoramento dovuto a droghe e alcol. Cobain prova empatia e affetto per uno spirito affine dal tragico destino. Magari in un mondo giusto, sarebbe stata la diva tra le dive. Ma state tranquilli: avrà la sua vendetta.

In “Frances Farmer Will Have Her Revenge on Seattle” Cobain proietta con terribile lucidità il suo futuro. Il tono è quello di colui che non ha più nulla da perdere. Il ritornello è straziante e annichilente: Cobain non sa bene più nemmeno quando è triste: «I lost the confort of being sad».

Poco da aggiungere: altro intaglio nero da mettere sull’incisione di In Utero. E il finale del brano è l’immagine definitiva. Il commiato assoluto e finale di Cobain e dello speculare modello Farmer: «Tornerà come il fuoco per bruciare tutti i bugiardi / lascerà un manto di cenere sulla terra.»

Essendo due angeli caduti, ora Kurt e Frances dividono lo stesso lembo di cielo, magari raccontandosi come sarebbero potute andare le cose. Per ingannare il tempo, progettano la loro vendetta su Seattle. E sul mondo.

Alessio Belli