אין שאַפּ, אָדער די סװעט־שאַפּ

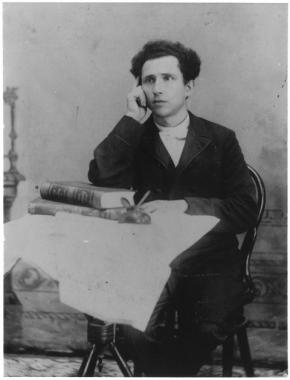

Moris Roznfeld [Morris Rosenfeld] / מאָריס ראָזנפֿעלדLangue: yiddish

עס רױשן אין שאַפּ אַזױ װילד די מאַשינען,

אַז אָפֿטמאָל פֿאַרגעס איך אין רױש דאָס איך בין; ―

איך װער אין דעם שרעקלעכן טומל פֿאַרלאָרן,

מײן איך װערט דאָרט בטל, איך װער אַ מאַשין;

איך אַרבעט, און אַרבעט אָן חשבון,

עס שאַפֿט זיך, און שאַפֿט זיך, און שאַפֿט זיך אָן צאָל;

פֿאַר װאָס? און פֿאַר װעמען? איך װײס ניט, איך פֿרעג ניט, ―

װי קומט אַ מאַשינע צו דענקען אַ מאָל?

ניט דאָ קײן געפֿיל, קײן געדאַנק, קײן פֿאַרשטאַנד גאָר: -

די ביטערע, בלוטיגע, אַרבעט דערשלאָגט

דאָס עדעלסטע, שײנסטע און בעסטע דאָס רײַכסטע,

דאָס טיפֿסטע, דאָס העכסטע װאָס לעבן פֿאַרמאָגט.

עס שװינדן סעקונדן, מינוטן און שטונדן,

גאָר זעגלשנעל לױפֿן די נעכט מיט די טעג; -

איך טרײַב די מאַשין גלײַך איך װיל זײ דעריאָגן,

איך יאָג אָן אַ שׂכל, איך יאָג אָן אַ ברעג

דער זײגער אין װאָרקשאַפ, ער רוט ניט אַפֿילו,

ער װײסט אַלץ, און קלאַפּט אַלץ, און װעקט נאָכאַנאַנד; -

געזאָגט האָט אַ מענטש מיר אַ מאָל די באַדײַטונג:

זײַן װײסן און װעקן, דאָרט לײגט אַ פֿאַרשטאַנד;

נאָר עטװאָס געדענקט זיך מיר, פּונקט װי פֿון חלום; -

דער זײגער, ער װעקט אין מיר לעבן און זין,

און נאָך עפּעס, - איך האָב פֿאַרגעסן, - ניט פֿרעגט עס!

איך װײס ניט, איך װײס ניט, איך בין אַ מאַשין!...

און צײַטנװײַז װען איך דערהער שױן דעם זײגער

פֿאַרשטײ איך גאַנץ אַנדערס זײַן װײַסן, זײַן שפּראַך,

מיר דאַכט, אַז עס נוקעט מיך אומרו,

'ך זאָל אַרבעטן, אַרבעטן, מערער אַ סך.

איך הער אין זײַן טאָן נאָר דעם באָס װילדן בײזער.

זײַן פֿינסטערן קוק אין די װײַסער די צװײ; -

דער זײגער, מיר סקרוכעט, מיר דאַכט אַז ער טרײַבט מיך

און רופֿט מיך: “מאַשינע!”, און שרײַט צו מיר: “נײ!”...

נאָר דאַן װען'ס איז שטילער דער װילדער געטומל,

אַװעק איז דער מײַסטער אין מיטאַגצײַטשטונד,

אָ, הײבט אין קאָפּ בײַ מיר גלײַך אָן צו טאָגן,

אין הערצן צו ציען, - איך פֿיל דאַן מײַן װוּנד; -

און ביטערע טרערן, און זודיקע טרײנען

באָנעצן מײַן מאָגערען מיטאַג, מײַן ברױט, -

עס װערגט מיך, איך קען ניט מער עסען, איך קען ניט!

אָ, שרעקליכע פּראַצע! אָ, ביטערע נױט!

'ס דערשײַנט מיר די שאַפּ מיטאָגצײַטשטונדע

אַ בלוטיגע שלאַכטפֿעלד, װען דאַרט װערד גערוט:

אַרום און אַרום זע איך ליגן הרוגים,

עס לאַרעמט פֿון ד'ערד דאָס פֿאַרגאָסנע בלוט...

אײן װײַלע, און באַלט װערד געפּױקט אַ טרעװאָגע,

די טױטע דערװאַכן, עס לעבט אױף די שלאַכט,

עס קעמפֿן די טרופּעס פֿאַר פֿרעמדע, פֿאַר פֿרעמדע,

און שטרײַטן, און פֿאַלן, און זינקן אין נאַכט.

איך קוק אױף דעם קאַמף־פּלאַן מיט ביטערן צרהן,

מיט שרעק, מיט נקמה, מיט העלישער פּײַן; ―

דער זײגער, יעצט הער איך אים ריכטיק, ער װעקט עס;

“אַ סוף צו די קנעכטשאַפֿט, אַ סוף זאָל עס זײַן!”

ער מינטערט אין מיר מײַן פֿאַרשטאַנד, די געפֿילן,

און װײַזט װי עס לױפֿן די שטונדן אַהין;

אַן עלנטער בלײַב איך, װי לאַנג איך װעל שװײַגן,

פֿאַרלאָרן, װי לאַנג איך פֿאַרבלײַב װאָס איך בין...

דער מענטש װעלכער שלאָפֿט אין מיר, הײבט אָן דערװאַכן,

דער קנעכט, װעלכער װאַכט אין מיר, שלאָפֿט דאַכט זיך אײַן; ―

אַצינד איז די ריכטיקע שטונדע געקומען!

אַ סוף צו דעם עלנט, אַ סוף זאָל עס זײַן!...

נאָר פּלוצלינג ― דער װיסטל, דער באָס ― אַ טרעװאָגע!

איך װער אָן דעם שׂכל, פֿאַרגעס, װוּ איך בין, ―

עס טומלט, מען קאַמפֿט, אָ, מײַן איך איז פֿאַרלאָרן, ―

איך װײס ניט, מיך אַרט ניט, איך בין אַ מאַשין... .

אַז אָפֿטמאָל פֿאַרגעס איך אין רױש דאָס איך בין; ―

איך װער אין דעם שרעקלעכן טומל פֿאַרלאָרן,

מײן איך װערט דאָרט בטל, איך װער אַ מאַשין;

איך אַרבעט, און אַרבעט אָן חשבון,

עס שאַפֿט זיך, און שאַפֿט זיך, און שאַפֿט זיך אָן צאָל;

פֿאַר װאָס? און פֿאַר װעמען? איך װײס ניט, איך פֿרעג ניט, ―

װי קומט אַ מאַשינע צו דענקען אַ מאָל?

ניט דאָ קײן געפֿיל, קײן געדאַנק, קײן פֿאַרשטאַנד גאָר: -

די ביטערע, בלוטיגע, אַרבעט דערשלאָגט

דאָס עדעלסטע, שײנסטע און בעסטע דאָס רײַכסטע,

דאָס טיפֿסטע, דאָס העכסטע װאָס לעבן פֿאַרמאָגט.

עס שװינדן סעקונדן, מינוטן און שטונדן,

גאָר זעגלשנעל לױפֿן די נעכט מיט די טעג; -

איך טרײַב די מאַשין גלײַך איך װיל זײ דעריאָגן,

איך יאָג אָן אַ שׂכל, איך יאָג אָן אַ ברעג

דער זײגער אין װאָרקשאַפ, ער רוט ניט אַפֿילו,

ער װײסט אַלץ, און קלאַפּט אַלץ, און װעקט נאָכאַנאַנד; -

געזאָגט האָט אַ מענטש מיר אַ מאָל די באַדײַטונג:

זײַן װײסן און װעקן, דאָרט לײגט אַ פֿאַרשטאַנד;

נאָר עטװאָס געדענקט זיך מיר, פּונקט װי פֿון חלום; -

דער זײגער, ער װעקט אין מיר לעבן און זין,

און נאָך עפּעס, - איך האָב פֿאַרגעסן, - ניט פֿרעגט עס!

איך װײס ניט, איך װײס ניט, איך בין אַ מאַשין!...

און צײַטנװײַז װען איך דערהער שױן דעם זײגער

פֿאַרשטײ איך גאַנץ אַנדערס זײַן װײַסן, זײַן שפּראַך,

מיר דאַכט, אַז עס נוקעט מיך אומרו,

'ך זאָל אַרבעטן, אַרבעטן, מערער אַ סך.

איך הער אין זײַן טאָן נאָר דעם באָס װילדן בײזער.

זײַן פֿינסטערן קוק אין די װײַסער די צװײ; -

דער זײגער, מיר סקרוכעט, מיר דאַכט אַז ער טרײַבט מיך

און רופֿט מיך: “מאַשינע!”, און שרײַט צו מיר: “נײ!”...

נאָר דאַן װען'ס איז שטילער דער װילדער געטומל,

אַװעק איז דער מײַסטער אין מיטאַגצײַטשטונד,

אָ, הײבט אין קאָפּ בײַ מיר גלײַך אָן צו טאָגן,

אין הערצן צו ציען, - איך פֿיל דאַן מײַן װוּנד; -

און ביטערע טרערן, און זודיקע טרײנען

באָנעצן מײַן מאָגערען מיטאַג, מײַן ברױט, -

עס װערגט מיך, איך קען ניט מער עסען, איך קען ניט!

אָ, שרעקליכע פּראַצע! אָ, ביטערע נױט!

'ס דערשײַנט מיר די שאַפּ מיטאָגצײַטשטונדע

אַ בלוטיגע שלאַכטפֿעלד, װען דאַרט װערד גערוט:

אַרום און אַרום זע איך ליגן הרוגים,

עס לאַרעמט פֿון ד'ערד דאָס פֿאַרגאָסנע בלוט...

אײן װײַלע, און באַלט װערד געפּױקט אַ טרעװאָגע,

די טױטע דערװאַכן, עס לעבט אױף די שלאַכט,

עס קעמפֿן די טרופּעס פֿאַר פֿרעמדע, פֿאַר פֿרעמדע,

און שטרײַטן, און פֿאַלן, און זינקן אין נאַכט.

איך קוק אױף דעם קאַמף־פּלאַן מיט ביטערן צרהן,

מיט שרעק, מיט נקמה, מיט העלישער פּײַן; ―

דער זײגער, יעצט הער איך אים ריכטיק, ער װעקט עס;

“אַ סוף צו די קנעכטשאַפֿט, אַ סוף זאָל עס זײַן!”

ער מינטערט אין מיר מײַן פֿאַרשטאַנד, די געפֿילן,

און װײַזט װי עס לױפֿן די שטונדן אַהין;

אַן עלנטער בלײַב איך, װי לאַנג איך װעל שװײַגן,

פֿאַרלאָרן, װי לאַנג איך פֿאַרבלײַב װאָס איך בין...

דער מענטש װעלכער שלאָפֿט אין מיר, הײבט אָן דערװאַכן,

דער קנעכט, װעלכער װאַכט אין מיר, שלאָפֿט דאַכט זיך אײַן; ―

אַצינד איז די ריכטיקע שטונדע געקומען!

אַ סוף צו דעם עלנט, אַ סוף זאָל עס זײַן!...

נאָר פּלוצלינג ― דער װיסטל, דער באָס ― אַ טרעװאָגע!

איך װער אָן דעם שׂכל, פֿאַרגעס, װוּ איך בין, ―

עס טומלט, מען קאַמפֿט, אָ, מײַן איך איז פֿאַרלאָרן, ―

איך װײס ניט, מיך אַרט ניט, איך בין אַ מאַשין... .

envoyé par Bernart Bartleby - 17/2/2014 - 11:46

Langue: yiddish

Il testo traslitterato:

Romanized lyrics

Romanized lyrics

Morris Rosenfeld.

Bernart Bartleby dubitava, e a ragione, che la traslitterazione da lui reperita fosse "correttissima". Infatti, si tratta della "solita" traslitterazione tedeschizzante, che impedirebbe una corretta ricostruzione del testo in caratteri ebraici. Indi per cui si è dovuto ricostruire anche la traslitterazione prima di procedere alla ritrascrizione in kvadratshrift. [RV]

IN SHAP, oder DI SVET-SHAP

Es royshn in shap azoy vild di mashinen,

Az oftmol farges ikh in roysh, dos ikh bin;-

Ikh ver in dem shreklekhn tuml farlorn -

Mayn ikh vert dort botel, ikh ver a mashin':

Ikh arbet, un arbet, un arbet, on kheshbn.

Es shaft zikh, un shaft zikh, un shaft zikh on tsol:

Far vos? Un far vemen? Ikh veys nit, ikh freg nit,-

Vi kumt a mashine tsu denkn a mol?......

Nit do keyn gefil, keyn gedank, keyn farshtand gor:-

Di bitere, blutige arbet dershlogt

Dos edelste, sheynste un beste dos raykhste,

Dos tifste, dos hekhste vos lebn farmogt.

Es shvindn sekundn, minutn un shtundn,

Gor zeglshnel loyfn di nekht mit di teg;-

Ikh trayb di mashin' glaykh ikh vil zey deryogn,

Ikh yog on a seykhl, ikh yog on a breg

Der zeyger in vorkshap, er rut nit afile,

Er veyst alts, un klapt alts, un vekt nokhanand;-

Gezogt hot a mentsh mir a mol di badaytung:

Zayn veysn un vekn, dort leygt a farshtand;

Nor etvos gedenkt zikh mir, punkt vi fun kholem;-

Der zeyger, er vekt in mir lebn un zin,

Un nokh epes, - ikh hob fargesn, - nit fregt es!

Ikh veys nit, ikh veys nit, ikh bin a mashin´!....

Un tsaytnvayz ven ikh derher shoyn dem zeyger

Farshtey ikh gants anders zayn vaysn, zayn shprakh,

Mir dakht, az es nuket mikh dortn der umru,

´kh zol arbetn, arbetn merer asakh.

Ikh her in zayn ton nor dem bos vildn beyzer.

Zayn finstern kuk in di vayser di tsvey;-

Der zeyger, mir skrukhet, mir dakht az er traybt mikh

Un ruft mikh: "Mashine!" un shrayt tsu mir: "Ney!"...

Nor dan ven´s iz shtiler der vilder getuml,

Avek iz der mayster in mitogtsaytshtund,

O, dan heybt in kop bay mir glaykh on tsu togn,

In hertsn tsu tsien, -ikh fil dan mayn vund;-

Un bitere trern, un zudike treynen

Banetsn mayn mogeren mitag, mayn broyt,-

Es vergt mikh, ikh ken nit mer esen, ikh ken nit!

O, shreklikhe pratse! O, bitere noyt!

´s Dershaynt mir di shap in der mitogtsaytshtunde

A blutige shlakhtfeld, ven dort verd gerut:

Arum un arum ze ikh lign harugim,

Es laremt fun d'erd dos fargosne blut...

Eyn vayle, un balt verd gepoykt a trevoge,

Di toyte dervakhn, es lebt oyf di shlakht,

Es kemfn di trupes far fremde, far fremde,

Un shtraytn, un faln, un zinkn in nakht.

Ikh kuk af dem kamfplats mit biteren tsoren,

Mit shrek, mit nekome, mit helisher payn ;-

Der zeyger, yetst hor ikh im rikhtik,er vekt es:

"A sof tsu di knekhtshaft, a sof zol es zayn!"

Er muntert in mir mayn farshtand, di gefiln,

Un vayzt vi es loyfn di shtundn ahin;

An elender blayb ikh, vi lang ikh vel shvaygn,

Farlorn, vi lang ikh farblayb, vos ikh bin...

Der mentsh, velkher shloft in mir, hobt on dervakhn,

Der knekht, velkher vakht in mir, shloft dort zikh ayn;-

Atsind iz di rikhtike shtunde gekumen!

A sof tsu dem elnt, a sof zol es zayn!....

Nor plutsling - der vistl, der bos, - a trevoge!

Ikh ver on dem seykhl, farges, vu ikh bin,-

Es tumlt, men kemft, o, mayn ikh iz farlorn,-

Ikh veys nit, mikh art nit, ikh bin a mashin...

Es royshn in shap azoy vild di mashinen,

Az oftmol farges ikh in roysh, dos ikh bin;-

Ikh ver in dem shreklekhn tuml farlorn -

Mayn ikh vert dort botel, ikh ver a mashin':

Ikh arbet, un arbet, un arbet, on kheshbn.

Es shaft zikh, un shaft zikh, un shaft zikh on tsol:

Far vos? Un far vemen? Ikh veys nit, ikh freg nit,-

Vi kumt a mashine tsu denkn a mol?......

Nit do keyn gefil, keyn gedank, keyn farshtand gor:-

Di bitere, blutige arbet dershlogt

Dos edelste, sheynste un beste dos raykhste,

Dos tifste, dos hekhste vos lebn farmogt.

Es shvindn sekundn, minutn un shtundn,

Gor zeglshnel loyfn di nekht mit di teg;-

Ikh trayb di mashin' glaykh ikh vil zey deryogn,

Ikh yog on a seykhl, ikh yog on a breg

Der zeyger in vorkshap, er rut nit afile,

Er veyst alts, un klapt alts, un vekt nokhanand;-

Gezogt hot a mentsh mir a mol di badaytung:

Zayn veysn un vekn, dort leygt a farshtand;

Nor etvos gedenkt zikh mir, punkt vi fun kholem;-

Der zeyger, er vekt in mir lebn un zin,

Un nokh epes, - ikh hob fargesn, - nit fregt es!

Ikh veys nit, ikh veys nit, ikh bin a mashin´!....

Un tsaytnvayz ven ikh derher shoyn dem zeyger

Farshtey ikh gants anders zayn vaysn, zayn shprakh,

Mir dakht, az es nuket mikh dortn der umru,

´kh zol arbetn, arbetn merer asakh.

Ikh her in zayn ton nor dem bos vildn beyzer.

Zayn finstern kuk in di vayser di tsvey;-

Der zeyger, mir skrukhet, mir dakht az er traybt mikh

Un ruft mikh: "Mashine!" un shrayt tsu mir: "Ney!"...

Nor dan ven´s iz shtiler der vilder getuml,

Avek iz der mayster in mitogtsaytshtund,

O, dan heybt in kop bay mir glaykh on tsu togn,

In hertsn tsu tsien, -ikh fil dan mayn vund;-

Un bitere trern, un zudike treynen

Banetsn mayn mogeren mitag, mayn broyt,-

Es vergt mikh, ikh ken nit mer esen, ikh ken nit!

O, shreklikhe pratse! O, bitere noyt!

´s Dershaynt mir di shap in der mitogtsaytshtunde

A blutige shlakhtfeld, ven dort verd gerut:

Arum un arum ze ikh lign harugim,

Es laremt fun d'erd dos fargosne blut...

Eyn vayle, un balt verd gepoykt a trevoge,

Di toyte dervakhn, es lebt oyf di shlakht,

Es kemfn di trupes far fremde, far fremde,

Un shtraytn, un faln, un zinkn in nakht.

Ikh kuk af dem kamfplats mit biteren tsoren,

Mit shrek, mit nekome, mit helisher payn ;-

Der zeyger, yetst hor ikh im rikhtik,er vekt es:

"A sof tsu di knekhtshaft, a sof zol es zayn!"

Er muntert in mir mayn farshtand, di gefiln,

Un vayzt vi es loyfn di shtundn ahin;

An elender blayb ikh, vi lang ikh vel shvaygn,

Farlorn, vi lang ikh farblayb, vos ikh bin...

Der mentsh, velkher shloft in mir, hobt on dervakhn,

Der knekht, velkher vakht in mir, shloft dort zikh ayn;-

Atsind iz di rikhtike shtunde gekumen!

A sof tsu dem elnt, a sof zol es zayn!....

Nor plutsling - der vistl, der bos, - a trevoge!

Ikh ver on dem seykhl, farges, vu ikh bin,-

Es tumlt, men kemft, o, mayn ikh iz farlorn,-

Ikh veys nit, mikh art nit, ikh bin a mashin...

envoyé par Bernart Bartleby - 17/2/2014 - 12:49

Langue: italien

Traduzione italiana di Riccardo Venturi

17 febbraio 2014

17 febbraio 2014

Prato, 1° dicembre 2013.

Una volta ricostruito il testo di questa cosa con la massima esattezza possibile, si è trattato di renderlo in italiano corrente. La traduzione inglese presente in questo sito, lo ripeto, è particolarmente bella e ben fatta; ma si tratta di un inglese estremamente d'arte, solenne e aulico, che non tutti potrebbero intendere (e che si prende, inoltre, diverse libertà). Questa mia traduzione non è così. E' particolarmente brutta, ma è stata fatta direttamente sul testo in yiddish e alla lettera; soltanto nella strofa, incredibilmente bella e terribile, dell' "orologio parlante", ho fatto qualche adattamento per meglio far capire il senso di ciò che viene espresso. Al termine della faticata che è costata questa pagina, e non soltanto a me, appare questa cosa che dà il senso esatto di quel che si fa qui. [RV]

IN OFFICINA, o NELLO SWEATSHOP

Qui in officina, le macchine fanno un rumore così d'inferno

Che, spesso, nel frastuono dimentico chi sono;

Mi perdo nel rumore terrificante, e mi sento

Come vuoto dentro: divento una macchina.

Lavoro, lavoro e lavoro, senza sosta.

Si produce e fabbrica, fabbrica e produce all'infinito:

Per che cosa? E per chi? Non lo so e non lo chiedo,

Una macchina, come può mai pensare?...

Qui, niente sentimenti, né pensieri, né ragione:

Il lavoro duro e sanguinoso schiaccia

Ciò che è più nobile e fine, migliore e più ricco,

Ciò che di più profondo e elevato ha la vita.

Scorrono i secondi, i minuti e le ore,

I giorni e le notti volan via come una vela al vento;

E io fo andare la macchina quasi volessi superarli,

Li rincorro come un pazzo, come un forsennato.

L'orologio in officina non si ferma mai,

Indica tutto, ticchetta tutto, tiene sempre svegli;

Mi ha detto uno, una volta, che cosa vuol dire

Quel suo indicare e tener svegli: c'è un motivo preciso.

Mi ricordo qualcosa, quasi fosse un sogno:

L'orologio risvegliava in me la vita e i sensi

E ancora qualcosa – ma non ricordo più, non chiedetemelo!

Non lo so, non lo so, io sono una macchina!...

E alle volte, quando sto ascoltando l'orologio

Sembra che mi parli, e capisco quel che dice:

Mi sembra che il suo ticchettio da impazzire

Mi spinga a lavorare, sgobbare, faticare di più.

Sento in quel ticchettio come la voce aspra del boss,

Come lui mi guarda cupo e dritto negli occhi;

L'orologio -tremo!- sembra che mi spinga

E mi chiama “Macchina!”, e mi grida “Cuci!”

Solo quando il frastuono tremendo cessa

E il boss se ne va per la pausa pranzo,

Allora nella mia testa è come sorgesse l'alba,

E dentro di me mi sento ancor più ferito.

E piango lacrime amare e brucianti

Che bagnano il mio magro pasto e il pane,

Mi soffocano...Non ce la fo più a mangiare, non posso!

Che orribile pena mi viene dal nero bisogno!

A mezzogiorno l'officina mi sembra

Un campo di guerra dopo la battaglia:

Intorno a me vedo i caduti a terra

E dal suolo urla il sangue versato.

Un attimo, ed ecco che suona la sirena,

I morti si svegliano e la battaglia ricomincia:

I cadaveri combattono per degli stranieri,

E lottano, e muoiono, e annegano nel buio.

Osservo il massacro con rabbia profonda,

Con orrore, con dolore, con voglia di vendetta;

Ma ora sento l'orologio che dice -e lo sento!-

“Basta con questa schiavitù, deve finire!”

E risveglia i me i sensi e la ragione,

Mi mostra quanto il tempo ormai vola via;

Resterò un disgraziato finché tacerò,

Sarò perso al mondo, se resterò quel che sono.

L'uomo che dorme in me comincia a svegliarsi

E lo schiavo in me comincia a addormentarsi;

Adesso è arrivata l'ora giusta!

Basta con la miseria, deve finire!

Ma, all'improvviso, il fischio: allarme, il boss!

Di nuovo forsennato, dimentico chi sono.

Frastuono, battaglia; e ancora mi perdo,

Non so, non importa. Io sono una macchina.

Qui in officina, le macchine fanno un rumore così d'inferno

Che, spesso, nel frastuono dimentico chi sono;

Mi perdo nel rumore terrificante, e mi sento

Come vuoto dentro: divento una macchina.

Lavoro, lavoro e lavoro, senza sosta.

Si produce e fabbrica, fabbrica e produce all'infinito:

Per che cosa? E per chi? Non lo so e non lo chiedo,

Una macchina, come può mai pensare?...

Qui, niente sentimenti, né pensieri, né ragione:

Il lavoro duro e sanguinoso schiaccia

Ciò che è più nobile e fine, migliore e più ricco,

Ciò che di più profondo e elevato ha la vita.

Scorrono i secondi, i minuti e le ore,

I giorni e le notti volan via come una vela al vento;

E io fo andare la macchina quasi volessi superarli,

Li rincorro come un pazzo, come un forsennato.

L'orologio in officina non si ferma mai,

Indica tutto, ticchetta tutto, tiene sempre svegli;

Mi ha detto uno, una volta, che cosa vuol dire

Quel suo indicare e tener svegli: c'è un motivo preciso.

Mi ricordo qualcosa, quasi fosse un sogno:

L'orologio risvegliava in me la vita e i sensi

E ancora qualcosa – ma non ricordo più, non chiedetemelo!

Non lo so, non lo so, io sono una macchina!...

E alle volte, quando sto ascoltando l'orologio

Sembra che mi parli, e capisco quel che dice:

Mi sembra che il suo ticchettio da impazzire

Mi spinga a lavorare, sgobbare, faticare di più.

Sento in quel ticchettio come la voce aspra del boss,

Come lui mi guarda cupo e dritto negli occhi;

L'orologio -tremo!- sembra che mi spinga

E mi chiama “Macchina!”, e mi grida “Cuci!”

Solo quando il frastuono tremendo cessa

E il boss se ne va per la pausa pranzo,

Allora nella mia testa è come sorgesse l'alba,

E dentro di me mi sento ancor più ferito.

E piango lacrime amare e brucianti

Che bagnano il mio magro pasto e il pane,

Mi soffocano...Non ce la fo più a mangiare, non posso!

Che orribile pena mi viene dal nero bisogno!

A mezzogiorno l'officina mi sembra

Un campo di guerra dopo la battaglia:

Intorno a me vedo i caduti a terra

E dal suolo urla il sangue versato.

Un attimo, ed ecco che suona la sirena,

I morti si svegliano e la battaglia ricomincia:

I cadaveri combattono per degli stranieri,

E lottano, e muoiono, e annegano nel buio.

Osservo il massacro con rabbia profonda,

Con orrore, con dolore, con voglia di vendetta;

Ma ora sento l'orologio che dice -e lo sento!-

“Basta con questa schiavitù, deve finire!”

E risveglia i me i sensi e la ragione,

Mi mostra quanto il tempo ormai vola via;

Resterò un disgraziato finché tacerò,

Sarò perso al mondo, se resterò quel che sono.

L'uomo che dorme in me comincia a svegliarsi

E lo schiavo in me comincia a addormentarsi;

Adesso è arrivata l'ora giusta!

Basta con la miseria, deve finire!

Ma, all'improvviso, il fischio: allarme, il boss!

Di nuovo forsennato, dimentico chi sono.

Frastuono, battaglia; e ancora mi perdo,

Non so, non importa. Io sono una macchina.

Langue: anglais

Traduzione inglese da “Songs of Labor and Other Poems” di Morris Rosenfeld, su Project Gutenberg

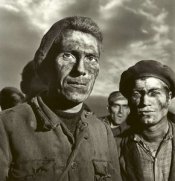

Dhaka, Bangladesh.

IN THE SWEAT-SHOP (IN THE FACTORY)

Oh, here in the shop the machines roar so wildly,

That oft, unaware that I am, or have been,

I sink and am lost in the terrible tumult;

And void is my soul... I am but a machine.

I work and I work and I work, never ceasing;

Create and create things from morning till e'en;

For what?--and for whom--Oh, I know not! Oh, ask not!

Who ever has heard of a conscious machine?

No, here is no feeling, no thought and no reason;

This life-crushing labor has ever supprest

The noblest and finest, the truest and richest,

The deepest, the highest and humanly best.

The seconds, the minutes, they pass out forever,

They vanish, swift fleeting like straws in a gale.

I drive the wheel madly as tho' to o'ertake them,--

Give chase without wisdom, or wit, or avail.

The clock in the workshop,--it rests not a moment;

It points on, and ticks on: Eternity--Time;

And once someone told me the clock had a meaning,--

Its pointing and ticking had reason and rhyme.

And this too he told me,--or had I been dreaming,--

The clock wakened life in one, forces unseen,

And something besides;... I forget what; Oh, ask not!

I know not, I know not, I am a machine.

At times, when I listen, I hear the clock plainly;--

The reason of old--the old meaning--is gone!

The maddening pendulum urges me forward

To labor and labor and still labor on.

The tick of the clock is the Boss in his anger!

The face of the clock has the eyes of a foe;

The clock--Oh, I shudder--dost hear how it drives me?

It calls me "Machine!" and it cries to me "Sew!"

At noon, when about me the wild tumult ceases,

And gone is the master, and I sit apart,

And dawn in my brain is beginning to glimmer,

The wound comes agape at the core of my heart;

And tears, bitter tears flow; ay, tears that are scalding;

They moisten my dinner--my dry crust of bread;

They choke me,--I cannot eat;--no, no, I cannot!

Oh, horrible toil I born of Need and of Dread.

The sweatshop at mid-day--I'll draw you the picture:

A battlefield bloody; the conflict at rest;

Around and about me the corpses are lying;

The blood cries aloud from the earth's gory breast.

A moment... and hark! The loud signal is sounded,

The dead rise again and renewed is the fight...

They struggle, these corpses; for strangers, for strangers!

They struggle, they fall, and they sink into night.

I gaze on the battle in bitterest anger,

And pain, hellish pain wakes the rebel in me!

The clock--now I hear it aright!--It is crying:

"An end to this bondage! An end there must be!"

It quickens my reason, each feeling within me;

It shows me how precious the moments that fly.

Oh, worthless my life if I longer am silent,

And lost to the world if in silence I die.

The man in me sleeping begins to awaken;

The thing that was slave into slumber has passed:

Now; up with the man in me! Up and be doing!

No misery more! Here is freedom at last!

When sudden: a whistle!--the Boss--an alarum!--

I sink in the slime of the stagnant routine;--

There's tumult, they struggle, oh, lost is my ego;--

I know not, I care not, I am a machine!...

Oh, here in the shop the machines roar so wildly,

That oft, unaware that I am, or have been,

I sink and am lost in the terrible tumult;

And void is my soul... I am but a machine.

I work and I work and I work, never ceasing;

Create and create things from morning till e'en;

For what?--and for whom--Oh, I know not! Oh, ask not!

Who ever has heard of a conscious machine?

No, here is no feeling, no thought and no reason;

This life-crushing labor has ever supprest

The noblest and finest, the truest and richest,

The deepest, the highest and humanly best.

The seconds, the minutes, they pass out forever,

They vanish, swift fleeting like straws in a gale.

I drive the wheel madly as tho' to o'ertake them,--

Give chase without wisdom, or wit, or avail.

The clock in the workshop,--it rests not a moment;

It points on, and ticks on: Eternity--Time;

And once someone told me the clock had a meaning,--

Its pointing and ticking had reason and rhyme.

And this too he told me,--or had I been dreaming,--

The clock wakened life in one, forces unseen,

And something besides;... I forget what; Oh, ask not!

I know not, I know not, I am a machine.

At times, when I listen, I hear the clock plainly;--

The reason of old--the old meaning--is gone!

The maddening pendulum urges me forward

To labor and labor and still labor on.

The tick of the clock is the Boss in his anger!

The face of the clock has the eyes of a foe;

The clock--Oh, I shudder--dost hear how it drives me?

It calls me "Machine!" and it cries to me "Sew!"

At noon, when about me the wild tumult ceases,

And gone is the master, and I sit apart,

And dawn in my brain is beginning to glimmer,

The wound comes agape at the core of my heart;

And tears, bitter tears flow; ay, tears that are scalding;

They moisten my dinner--my dry crust of bread;

They choke me,--I cannot eat;--no, no, I cannot!

Oh, horrible toil I born of Need and of Dread.

The sweatshop at mid-day--I'll draw you the picture:

A battlefield bloody; the conflict at rest;

Around and about me the corpses are lying;

The blood cries aloud from the earth's gory breast.

A moment... and hark! The loud signal is sounded,

The dead rise again and renewed is the fight...

They struggle, these corpses; for strangers, for strangers!

They struggle, they fall, and they sink into night.

I gaze on the battle in bitterest anger,

And pain, hellish pain wakes the rebel in me!

The clock--now I hear it aright!--It is crying:

"An end to this bondage! An end there must be!"

It quickens my reason, each feeling within me;

It shows me how precious the moments that fly.

Oh, worthless my life if I longer am silent,

And lost to the world if in silence I die.

The man in me sleeping begins to awaken;

The thing that was slave into slumber has passed:

Now; up with the man in me! Up and be doing!

No misery more! Here is freedom at last!

When sudden: a whistle!--the Boss--an alarum!--

I sink in the slime of the stagnant routine;--

There's tumult, they struggle, oh, lost is my ego;--

I know not, I care not, I am a machine!...

envoyé par Bernart Bartleby - 17/2/2014 - 11:47

Langue: anglais

La traduzione inglese (frammentaria) dal blog The Arty Semite.

English translation of a fragment of the poem, from the blog The Arty Semite.

La presente traduzione (incompleta) proviene dal blog di Ezra Glinter (che è, presumibilmente, l'autore della traduzione stessa). Rispetto alla traduzione d'arte presente in questa pagina, presenta il vantaggio di una lingua più facilmente comprensibile -agli anglofoni stessi, oserei dire. Interessante la breve introduzione presente sulla pagina:

English translation of a fragment of the poem, from the blog The Arty Semite.

La presente traduzione (incompleta) proviene dal blog di Ezra Glinter (che è, presumibilmente, l'autore della traduzione stessa). Rispetto alla traduzione d'arte presente in questa pagina, presenta il vantaggio di una lingua più facilmente comprensibile -agli anglofoni stessi, oserei dire. Interessante la breve introduzione presente sulla pagina:

Morris Rosenfeld, born in 1862 in Russian Poland, became famous in the early 20th century as one of the Yiddish “sweatshop poets” of New York. When the Triangle Waist Company fire killed 146 workers on March 25, 1911, Rosenfeld responded with a poem printed on the front page of the Forward. (To commemorate the 100th anniversary of the fire, the Forward is sponsoring a poetry contest — see here for details.)

It didn’t take a tragedy, however, to prompt Rosenfeld to lament the poor labor conditions that characterized the lives of many immigrants. In another poem titled simply “The Sweatshop,” translated by Forward Association Vice President Barnett Zumoff and published in “Pearls of Yiddish Poetry,” Rosenfeld described the drudgery of menial labor and the constricting effect it had on the life of mind and spirit. While the world of Lower East Side garment factories is now part of history, sweatshop labor has far from disappeared.

It didn’t take a tragedy, however, to prompt Rosenfeld to lament the poor labor conditions that characterized the lives of many immigrants. In another poem titled simply “The Sweatshop,” translated by Forward Association Vice President Barnett Zumoff and published in “Pearls of Yiddish Poetry,” Rosenfeld described the drudgery of menial labor and the constricting effect it had on the life of mind and spirit. While the world of Lower East Side garment factories is now part of history, sweatshop labor has far from disappeared.

THE SWEATSHOP (FRAGMENT)

The machines are so wildly noisy in the shop

That I often forget who I am.

I get lost in the frightful tumult —

My self is destroyed, I become a machine.

I work and work and work endlessly —

I create and create and create

Why? For whom? I don’t know and I don’t ask.

What business has a machine thinking?

I have no feelings, no thoughts, no understanding.

The bitter, bloody work suppresses

The noblest, most beautiful, best, richest,

Deepest, and highest things that life possesses.

Seconds, minutes, and hours go by — the days and nights sail past quickly.

I run the machine as if I wanted to overtake them —

I race mindlessly, endlessly.

The clock in the shop never rests —

It shows everything, strikes constantly, wakes us constantly.

Someone once explained it to me:

“In its showing and waking lies understanding.”

But I seem to remember something, as if from a dream:

The clock awakens life and understanding in me,

And something else — I forget what. Don’t ask!

I don’t know, I don’t know! I’m a machine!

At times, when I hear the clock,

I understand its showing and its language quite differently;

It seems to me that the pendulum urges me:

“Work, work, work a lot!”

I hear in its tones only the boss’s anger, his dark look.

The clock, it seems to me, drives me,

Gnashes its teeth, calls me “machine,” and yells at me: “Go!”

But when the wild tumult dies down

And the boss goes away for his lunch hour,

Dawn begins to break in my mind

And things tug at my heart.

Then I feel my wound,

And bitter, burning tears

Soak my meager lunch, my bread.

I feel choked up and I can’t eat any more — I can’t!

Oh, frightful toil! Oh, bitter poverty!

The human being that is sleeping within me

begins to awake —

the slave that is awake in me

seems to fall asleep.

Now the right hour has struck!

An end to loneliness — let there be an end to it!

But suddenly the whistle, the “boss,” sounds an alarm!

I lose my mind, I forget who I am.

There’s tumult and struggling — my self is lost.

I don’t know, I don’t care — I am a machine!

The machines are so wildly noisy in the shop

That I often forget who I am.

I get lost in the frightful tumult —

My self is destroyed, I become a machine.

I work and work and work endlessly —

I create and create and create

Why? For whom? I don’t know and I don’t ask.

What business has a machine thinking?

I have no feelings, no thoughts, no understanding.

The bitter, bloody work suppresses

The noblest, most beautiful, best, richest,

Deepest, and highest things that life possesses.

Seconds, minutes, and hours go by — the days and nights sail past quickly.

I run the machine as if I wanted to overtake them —

I race mindlessly, endlessly.

The clock in the shop never rests —

It shows everything, strikes constantly, wakes us constantly.

Someone once explained it to me:

“In its showing and waking lies understanding.”

But I seem to remember something, as if from a dream:

The clock awakens life and understanding in me,

And something else — I forget what. Don’t ask!

I don’t know, I don’t know! I’m a machine!

At times, when I hear the clock,

I understand its showing and its language quite differently;

It seems to me that the pendulum urges me:

“Work, work, work a lot!”

I hear in its tones only the boss’s anger, his dark look.

The clock, it seems to me, drives me,

Gnashes its teeth, calls me “machine,” and yells at me: “Go!”

But when the wild tumult dies down

And the boss goes away for his lunch hour,

Dawn begins to break in my mind

And things tug at my heart.

Then I feel my wound,

And bitter, burning tears

Soak my meager lunch, my bread.

I feel choked up and I can’t eat any more — I can’t!

Oh, frightful toil! Oh, bitter poverty!

The human being that is sleeping within me

begins to awake —

the slave that is awake in me

seems to fall asleep.

Now the right hour has struck!

An end to loneliness — let there be an end to it!

But suddenly the whistle, the “boss,” sounds an alarm!

I lose my mind, I forget who I am.

There’s tumult and struggling — my self is lost.

I don’t know, I don’t care — I am a machine!

envoyé par Riccardo Venturi - 18/2/2014 - 21:32

Langue: français

Version française – À L'ATELIER DE COUTURE – Marco Valdo M.I. – 2014

d'après la version italienne de Riccardo venturi

d'une chanson yiddish – In shap, oder Di svet-shap - Moris Roznfeld [Morris Rosenfeld] – 1893 ?

Poème de Morris Rosenfeld, originairement publié dans la revue « Di Tsukunft » (« Le Futur »),

ensuite, peut-être, dans le recueil intitulé « Lider-bukh », traduite en anglais en 1898 et en allemand en 1902.

d'après la version italienne de Riccardo venturi

d'une chanson yiddish – In shap, oder Di svet-shap - Moris Roznfeld [Morris Rosenfeld] – 1893 ?

Poème de Morris Rosenfeld, originairement publié dans la revue « Di Tsukunft » (« Le Futur »),

ensuite, peut-être, dans le recueil intitulé « Lider-bukh », traduite en anglais en 1898 et en allemand en 1902.

J'ai eu une étrange sensation en traduisant cette chanson qui me rappelait soudain mon grand-père qui fut lui aussi ouvrier tailleur... Évidemment, quand je l'ai connu l'ouvrier de ses débuts était devenu artisan, puis maître tailleur... Et puis, plus rien... son métier était mort... Il l'a suivi quelques temps plus tard... Ceci dit, il y a plusieurs chansons autour de l'atelier de couture ou de tissage... C'est une chanson qui pourrait se retrouver dans un parcours des chansons autour du « textile »... Mais attends un peu... J'essaye de me souvenir... Il y a évidemment Les Canuts, Les Fileuses, la Complainte des tisserandes, Les pauvres Fileuses, Grève de femmes au Bangladesh et sans doute encore d'autres...

Et elles nous plaisent bien à nous qui nous revendiquons comme des canuts, dont la tâche consiste à tisser jour après jour le linceul de ce vieux monde de détresse, d'exploitation, dominateur, oppressant et cacochyme.

Heureusement !

Ainsi Parlaient Marco Valdo M.I. et Lucien Lane

Et elles nous plaisent bien à nous qui nous revendiquons comme des canuts, dont la tâche consiste à tisser jour après jour le linceul de ce vieux monde de détresse, d'exploitation, dominateur, oppressant et cacochyme.

Heureusement !

Ainsi Parlaient Marco Valdo M.I. et Lucien Lane

À L'ATELIER DE COUTURE

Ici à l'atelier, règne le chahut infernal des machines

Souvent, dans ce vacarme, j'oublie qui je suis ;

Dans ce bruit terrifiant, je me perds et je suis

Comme vide : je deviens une machine.

Travail, travail, travail, sans s'arrêter.

On produit, on fabrique, on fabrique, on produit à l'infini :

Je ne sais pas, je ne demande pas pourquoi ? Et pour qui ?

Une machine, peut-elle jamais penser ? …

Ici, il n'y a aucun sentiment, ni raison, ni pensée,

Le travail dur et brutal anéantit

Tout : le fin, le bien, le bon, le sensé,

Tout ce qui donne ses dimensions à la vie.

Les secondes, les minutes, les heures, les journées

Volent comme voiles au vent, les jours et les nuits ;

Et moi, je pédale à ma machine pour les dépasser,

Je les poursuis comme un fou, comme un forcené.

L'horloge à l'atelier jamais ne s'arrête,

Elle scande tout, tic-tac – tic-tac, et tout toujours réveille;

Ce qu'elle veut dire, quelqu'un autrefois me l'a dit,

Scander et tenir éveillés : c'est un motif précis.

Je me rappelle quelque chose, comme un rêve :

L'horloge réveillait sens et vie en moi

Et encore autre chose – mais j'ai oublié quoi, ne me le demandez pas !

Je ne sais pas, je ne sais pas, je suis une machine ! …

Et parfois, quand j'écoute l'horloge

Elle me parle, et moi, je comprends ce qu'elle dit ;

Son tic-tac à devenir fou, ce tic-tac maudit

Pousse à travailler, trimer, peiner davantage.

Dans ce tic-tac, j'entends la voix âpre du patron,

Comme lui, droit dans les yeux, elle me regarde ;

L'horloge me pousse, j'en ai des frissons

Elle crie « Couds ! » et m'appelle « Machine ! ».

Seulement quand cesse cet effroyable vacarme

Et que le boss part pour la pause déjeuner,

Alors dans ma tête l'aube se lève ,

Et en moi, je me sens encore plus blessé.

Et je pleure d'amères et brûlantes larmes

Elles mouillent mon dîner – ma croûte de pain,

Elles me suffoquent… je n'arrive pas à manger, impossible !

Quelle terrible peine, quel horrible destin !

À midi, l'atelier ressemble

À un champ après la bataille

Autour de moi, je vois les morts à terre

Et sur sol, le sang versé se lamente

Une trêve, et soudain sonne la sirène,

Les morts ressuscitent et la bataille recommence :

Les cadavres se battent pour des étrangers,

Ils luttent, meurent et se noient dans l'obscurité.

Je contemple ce massacre avec une rage amère,

Avec horreur, avec douleur, j'aspire à la vengeance ;

Mais voilà que j'entends l'horloge dire

« Assez cet esclavage, ça doit finir ! »

Elle réveille mes sens et ma raison,

Et me montre comme le temps maintenant fuit ;

Je resterai malheureux tant que je me tairai,

Je serai perdu au monde, si je reste ce que je suis

L'homme qui dort en moi commence à se réveiller

Et l'esclave en moi commence à s'endormir ;

Maintenant, le bon moment est arrivé !

Suffit avec la misère, ça doit finir !

Mais, tout à coup, le sifflet : alerte, le patron !

J'oublie ma résolution ; à nouveau, je turbine.

Vacarme, combat ; et puis, je touche le fond.

Je ne sais pas, peu importe. Je suis une machine.

Ici à l'atelier, règne le chahut infernal des machines

Souvent, dans ce vacarme, j'oublie qui je suis ;

Dans ce bruit terrifiant, je me perds et je suis

Comme vide : je deviens une machine.

Travail, travail, travail, sans s'arrêter.

On produit, on fabrique, on fabrique, on produit à l'infini :

Je ne sais pas, je ne demande pas pourquoi ? Et pour qui ?

Une machine, peut-elle jamais penser ? …

Ici, il n'y a aucun sentiment, ni raison, ni pensée,

Le travail dur et brutal anéantit

Tout : le fin, le bien, le bon, le sensé,

Tout ce qui donne ses dimensions à la vie.

Les secondes, les minutes, les heures, les journées

Volent comme voiles au vent, les jours et les nuits ;

Et moi, je pédale à ma machine pour les dépasser,

Je les poursuis comme un fou, comme un forcené.

L'horloge à l'atelier jamais ne s'arrête,

Elle scande tout, tic-tac – tic-tac, et tout toujours réveille;

Ce qu'elle veut dire, quelqu'un autrefois me l'a dit,

Scander et tenir éveillés : c'est un motif précis.

Je me rappelle quelque chose, comme un rêve :

L'horloge réveillait sens et vie en moi

Et encore autre chose – mais j'ai oublié quoi, ne me le demandez pas !

Je ne sais pas, je ne sais pas, je suis une machine ! …

Et parfois, quand j'écoute l'horloge

Elle me parle, et moi, je comprends ce qu'elle dit ;

Son tic-tac à devenir fou, ce tic-tac maudit

Pousse à travailler, trimer, peiner davantage.

Dans ce tic-tac, j'entends la voix âpre du patron,

Comme lui, droit dans les yeux, elle me regarde ;

L'horloge me pousse, j'en ai des frissons

Elle crie « Couds ! » et m'appelle « Machine ! ».

Seulement quand cesse cet effroyable vacarme

Et que le boss part pour la pause déjeuner,

Alors dans ma tête l'aube se lève ,

Et en moi, je me sens encore plus blessé.

Et je pleure d'amères et brûlantes larmes

Elles mouillent mon dîner – ma croûte de pain,

Elles me suffoquent… je n'arrive pas à manger, impossible !

Quelle terrible peine, quel horrible destin !

À midi, l'atelier ressemble

À un champ après la bataille

Autour de moi, je vois les morts à terre

Et sur sol, le sang versé se lamente

Une trêve, et soudain sonne la sirène,

Les morts ressuscitent et la bataille recommence :

Les cadavres se battent pour des étrangers,

Ils luttent, meurent et se noient dans l'obscurité.

Je contemple ce massacre avec une rage amère,

Avec horreur, avec douleur, j'aspire à la vengeance ;

Mais voilà que j'entends l'horloge dire

« Assez cet esclavage, ça doit finir ! »

Elle réveille mes sens et ma raison,

Et me montre comme le temps maintenant fuit ;

Je resterai malheureux tant que je me tairai,

Je serai perdu au monde, si je reste ce que je suis

L'homme qui dort en moi commence à se réveiller

Et l'esclave en moi commence à s'endormir ;

Maintenant, le bon moment est arrivé !

Suffit avec la misère, ça doit finir !

Mais, tout à coup, le sifflet : alerte, le patron !

J'oublie ma résolution ; à nouveau, je turbine.

Vacarme, combat ; et puis, je touche le fond.

Je ne sais pas, peu importe. Je suis une machine.

envoyé par Marco Valdo M.I. - 18/2/2014 - 15:22

Ho cominciato a rimettere la pagina e a ricostruire le parti mancanti del testo in alfabeto ebraico (nella pagina da te indicata sono date la prima strofa e le ultime due). La traduzione inglese è perfetta, forse ti ha un po'...dato da pensare perché è scritta veramente in un inglese arcaico ("I know not" e roba del genere) e solenne, ma ti assicuro che si tratta, anzi, di una lingua veramente sostenuta, "high-falutin" come si dice in inglese. Chi ha fatto la traduzione, la ha fatta in quel tipo di inglese ottocentesco che era normalmente usato nelle canzoni del movimento dei lavoratori (ad esempio anche nella versione inglese dell' Internazionale) e che era in gran parte ripreso dalle ballate popolari (le ballate da "broadsides", più erano destinate al popolino e più erano scritte in un inglese roboante); era una cosa normale in ogni lingua, si pensi solo ai canti operai e anarchici italiani... Qualche stranezza, casomai, c'è nel testo traslitterato: versi mancanti qua e là, le solite traslitterazioni tedeschizzanti...

Riccardo Venturi - 17/2/2014 - 13:00

Così tanto per calarsi nell'atmosfera e nelle condizioni di uno sweastshop, per rifare questa pagina ci ho messo praticamente una giornata intera. Da diventarci pazzi. A un certo punto avrei preso chi ha fatto la traslitterazione e lo avrei infilato in un'impastatrice; ma neppure la parte del testo in caratteri ebraici già presente in rete era esente da pecche e incongruenze. Purtroppo, coi testi in yiddish è pane quotidiano, e solo l'incredibile importanza (e bellezza) che hanno spinge a andare avanti e a volerli riportare qui in una forma decente.

Ad ogni modo, pregherei Bernart di leggere bene questo commento e, possibilmente, di stamparselo. Contiene alcune "dritte" per lavorare meglio, d'ora in poi.

Le "dritte" riguardano il riconoscimento delle "traslitterazioni tedeschizzanti" dei testi, autentica calamità. La traslitterazione presente su "Nice Words", il blog dal quale è stata ripresa in origine, è per l'appunto tedeschizzante al massimo, oltre che scorretta in diversi punti. Caro Bernart, tieni quindi presente quanto segue. Una trascrizione è "tedeschizzante" quando:

Nel caso di testi molto lunghi e complessi come questi, se vedi cose del genere ti pregherei di aspettare a inserire il testo nel sito e di contattarmi prima (grazie).

Ti ricordo che la traslitterazione dello yiddish obbedisce a dei criteri ben precisi che sono stati fissati da un istituto, lo YIVO, che è stato fondato e ha avuto sede fino al 1939 a Vilnius. Poi ha dovuto all'improvviso trasferirsi a New York, Manhattan, 16a Strada. Chissà perché. Anche per questo detesto le trascrizioni tedeschizzanti.

Saluti cari!

Ad ogni modo, pregherei Bernart di leggere bene questo commento e, possibilmente, di stamparselo. Contiene alcune "dritte" per lavorare meglio, d'ora in poi.

Le "dritte" riguardano il riconoscimento delle "traslitterazioni tedeschizzanti" dei testi, autentica calamità. La traslitterazione presente su "Nice Words", il blog dal quale è stata ripresa in origine, è per l'appunto tedeschizzante al massimo, oltre che scorretta in diversi punti. Caro Bernart, tieni quindi presente quanto segue. Una trascrizione è "tedeschizzante" quando:

a. Presenta grafie come "ch" e "w" al posto di "kh" e "v" (ad esempio "nacht" e "wild" al posto di "nakht" e "vild") ;

b. Presenta all'inizio delle parole "s" al posto di "z" (ad esempio: "sich", "sayn", "sinkn" al posto di "zikh", "zayn", "zinkn");

c. Presenta all'inizio delle parole "st, sp" al posto di "sht, shp" (ad esempio "stund", "sprach" al posto di "shtund, shprakh");

d. Presenta all'inizio delle parole "er-" al posto di "der-" (ad esempio: "erwacht" al posto di "dervakht");

e. Presenta all'inizio delle parole "be-" al posto di "ba-" (ad esempio "bedaytung" al posto di "badaytung";

f. Presenta "j" al posto di "y" (ad esempio "derjogt" al posto di "deryogt");

g. Presenta la grafia "pf" al posto di "f" (ad esempio: "kampf" al posto di "kamf");

h. Infine, presenta (specie all'inizio delle parole) la grafia "v" al posto di "f" (ad esempio "varloyrn" al posto di "farlorn").

b. Presenta all'inizio delle parole "s" al posto di "z" (ad esempio: "sich", "sayn", "sinkn" al posto di "zikh", "zayn", "zinkn");

c. Presenta all'inizio delle parole "st, sp" al posto di "sht, shp" (ad esempio "stund", "sprach" al posto di "shtund, shprakh");

d. Presenta all'inizio delle parole "er-" al posto di "der-" (ad esempio: "erwacht" al posto di "dervakht");

e. Presenta all'inizio delle parole "be-" al posto di "ba-" (ad esempio "bedaytung" al posto di "badaytung";

f. Presenta "j" al posto di "y" (ad esempio "derjogt" al posto di "deryogt");

g. Presenta la grafia "pf" al posto di "f" (ad esempio: "kampf" al posto di "kamf");

h. Infine, presenta (specie all'inizio delle parole) la grafia "v" al posto di "f" (ad esempio "varloyrn" al posto di "farlorn").

Nel caso di testi molto lunghi e complessi come questi, se vedi cose del genere ti pregherei di aspettare a inserire il testo nel sito e di contattarmi prima (grazie).

Ti ricordo che la traslitterazione dello yiddish obbedisce a dei criteri ben precisi che sono stati fissati da un istituto, lo YIVO, che è stato fondato e ha avuto sede fino al 1939 a Vilnius. Poi ha dovuto all'improvviso trasferirsi a New York, Manhattan, 16a Strada. Chissà perché. Anche per questo detesto le trascrizioni tedeschizzanti.

Saluti cari!

Riccardo Venturi - 17/2/2014 - 20:24

Capisco e ci proverò, anche se non sarà facile per me che non conosco la lingua.

Ti ringrazio per il lavoro immane cui sei costretto, per amore della correttezza e della lingua e anche per il rispetto di tutti quei milioni di morti ai quali la lingua cercarono di cavargliela, insieme alla vita.

Ti ringrazio per il lavoro immane cui sei costretto, per amore della correttezza e della lingua e anche per il rispetto di tutti quei milioni di morti ai quali la lingua cercarono di cavargliela, insieme alla vita.

Bernart Bartleby - 17/2/2014 - 21:34

Credo proprio che tu abbia centrato la cosa, Bernart. In questa particolare sezione del sito, sento il senso preciso di quando si dice "dare voce a chi non la ha più". Non la ha più perché è stato spazzato via; nei lager del lavoro ancor prima che in quelli dei nazisti. La lingua dei morti, sempre quella.

È vero, ci sto faticando su questi testi. Nulla, ovviamente, in confronto alla fatica che dovettero passare quegli uomini, quelle donne, fino a morirne. Quel che posso fare, è riprodurre nel modo più esatto possibile le parole che scrissero per testimoniare il loro dolore e le loro lotte, in una fabbrica come a Dachau. Anche per questo sono immensamente incavolato con chi tratta questi testi con inesattezza e faccio veramente le pulci, al peggio del peggio della mia pignoleria.

Perché, poi, una volta ricostruito il testo, appaiono cose come questa, di questa pagina. E sono ancora qui senza fiato, coi bordoni addosso. Appare ancor più chiaro il senso delle foto che hai, giustamente, messo a corredo dell'introduzione. Appaiono le ombre di Morris Rosenfeld, che viveva di persona quel che scriveva, e dei suoi compagni di schiavitù; e appaiono le ombre degli schiavi di oggi, delle fabbriche che crollano in India e nel Bangladesh producendo inutile merda per il nostro mondo, dei lavoratori cinesi che bruciano ammassati in una fabbrica a Prato.

Non è certamente un caso se, all'ingresso di Auschwitz e degli altri lager vi fosse la scritta "Il lavoro rende liberi". L'estrema beffa del padrone, che sia vestito da Himmler o da Benetton, da Amon Goeth o da Dolce & Gabbana. Si chiamano Vittime del Capitale. A volte il Capitale ha la camicia nera o bruna, a volte la ha bellina alla moda dello "stilista". Gli sweatshops erano in gran parte officine tessili. In Bangladesh e in India sono officine tessili. A Prato sono officine tessili.

Allora mi dico: Riccardo, fai quel che sai fare e fai conoscere queste parole assieme agli altri. E non importa se non ci guadagni un soldo. Saluti

È vero, ci sto faticando su questi testi. Nulla, ovviamente, in confronto alla fatica che dovettero passare quegli uomini, quelle donne, fino a morirne. Quel che posso fare, è riprodurre nel modo più esatto possibile le parole che scrissero per testimoniare il loro dolore e le loro lotte, in una fabbrica come a Dachau. Anche per questo sono immensamente incavolato con chi tratta questi testi con inesattezza e faccio veramente le pulci, al peggio del peggio della mia pignoleria.

Perché, poi, una volta ricostruito il testo, appaiono cose come questa, di questa pagina. E sono ancora qui senza fiato, coi bordoni addosso. Appare ancor più chiaro il senso delle foto che hai, giustamente, messo a corredo dell'introduzione. Appaiono le ombre di Morris Rosenfeld, che viveva di persona quel che scriveva, e dei suoi compagni di schiavitù; e appaiono le ombre degli schiavi di oggi, delle fabbriche che crollano in India e nel Bangladesh producendo inutile merda per il nostro mondo, dei lavoratori cinesi che bruciano ammassati in una fabbrica a Prato.

Non è certamente un caso se, all'ingresso di Auschwitz e degli altri lager vi fosse la scritta "Il lavoro rende liberi". L'estrema beffa del padrone, che sia vestito da Himmler o da Benetton, da Amon Goeth o da Dolce & Gabbana. Si chiamano Vittime del Capitale. A volte il Capitale ha la camicia nera o bruna, a volte la ha bellina alla moda dello "stilista". Gli sweatshops erano in gran parte officine tessili. In Bangladesh e in India sono officine tessili. A Prato sono officine tessili.

Allora mi dico: Riccardo, fai quel che sai fare e fai conoscere queste parole assieme agli altri. E non importa se non ci guadagni un soldo. Saluti

Riccardo Venturi - 17/2/2014 - 21:48

Per cominciare mi sono stampato la tua legenda sulle translitterazioni tedeschizzanti che - ora lo so - sono da aborrire (Pensa un po' te, manco conosco la lingua è se appena un termine mi appare "tedeschizzante" adesso già lo odio)...

Un'altra cosa, il comando di allineamento da destra, quello che chiami "direction:rtl", è il classico "Ctrl+Shift+D", quello che ha anche la sua icona nella barra di formattazione di Word? E basta quello perchè poi il testo risulti corretto nell'orientamento uno volta postato sul sito? Il comando va applicato prima di incollare su Word o al testo già incollato?

Un'altra cosa, il comando di allineamento da destra, quello che chiami "direction:rtl", è il classico "Ctrl+Shift+D", quello che ha anche la sua icona nella barra di formattazione di Word? E basta quello perchè poi il testo risulti corretto nell'orientamento uno volta postato sul sito? Il comando va applicato prima di incollare su Word o al testo già incollato?

Bernart Bartleby - 17/2/2014 - 22:08

Il comando direction:rtl è nel campo stile del db che al momento non è accessibile a chi non è amministratore.

il Webmastro - 17/2/2014 - 22:13

Non credo proprio di poter copiare correttamente in Word un testo destra-sinistra come l'ebraico... Dovrei installare prima di tutto un supporto per le lingue aggiuntive che però richiede il disco d'installazione... Inoltre a casa non uso nemmeno Word di Windows ma un programma di scrittura (Softmaker Free) molto meno sofisticato... Come posso fare?

Bernart Bartleby - 18/2/2014 - 09:35

×

![]()

[1893?]

Versi di Morris Rosenfeld, originariamente pubblicati sulla rivista “Di Tsukunft” (“Il Futuro”), poi, forse, nella raccolta intitolata "Lider-bukh", tradotta in inglese nel 1898 e in tedesco nel 1902.

Purtroppo sono riuscito a trovare solo un testo parziale in caratteri ebraici, così comincio a contribuire quello traslitterato (Riccaaardooo, pensaci tuuu!!!).

La traslitterazione – non so se sia correttissima - l’ho trovata sul blog Nice Words