Like most girls of her generation she was clever with needle and thread,

Preparing with hope for the future, coverlets for both table and bed.

Every petticoat, bonnet and linen was carefully folded away,

Then stored in a drawer or a camphor wood chest awaiting her wedding day.

There were cottons to wear in the summer. For winter some woolens were best.

As the hem of her apron was finished she put it away with the rest.

She learned how to sew by eleven and continued on throughout her life.

When love came to her she was twenty. She took vows as a coal miner’s wife.

The cabins that made up the village had slab sides and plain wooden floors,

A room with a table, a simple bed and fuel burning stove by the doors.

The wash tub stood out by the tank stand with the copper and stick leaning by.

The hem of her apron was sodden as she hung the wet clothes out to dry.

By noon on each Tuesday and Friday she had baked on her mother’s advice

Batches of biscuits and meat pies and fruit pies, bread that was crusty to slice.

Instead of the scraps of old fabric she had sewn to a thick padded square,

Sometimes she would use just a dish cloth to handle the hot pans with care.

Her baking would cool on the table then she’d wrap them and store them away.

The hem of her apron was crusty with the flour and grease from the tray.

Her usual habit was order and that Thursday she scrubbed the board floor.

She mopped and she dusted, moving the soot then sweeping it all out the door.

The force of the blast nearly floored her. First she felt it then she heard the sound.

Her instinct told her there was peril to the souls who were still underground.

Then she rose and in great trepidation she joined with the rest of the line.

The hem of her apron grew dusty from the road as she ran to the mine.

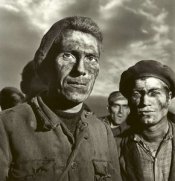

A full shift of men had been working at the time of that earth shaking blast.

Her husband had not made the surface. She would hold on with hope ‘til the last.

With each one they dragged from the rubble she would look and then sigh with relief

Over bodies of men who’d been robbed of life. This time coal was the thief.

She joined with a small band of others, and the priest, seeking comfort in Psalms.

The hem of her apron was crumpled as she crushed it between anxious palms.

Circumstance can make heroes of many. The humblest can often be brave.

From the darkness she saw stumbling figures helping others to walk from the cave.

All at once he broke through to the sunlight. The darkness had felt like a shroud.

Passing on his companion to others, he searched for her face in the crowd.

With a small cry of joy she ran forward and he stooped to receive her embrace.

The hem of her apron was blackened as she wiped dirt and tears from his face.

It was only three hours she waited in the dust and the crowd and the chill

And though he returned there were others who, remaining below them, were still.

That July in the mine at Mt Kembla, ninety six men were lost to coal.

We remember them still with a tribute, each one is a martyred soul.

Round the world there are millions of miners. Disaster can occur any day.

The hem of her apron’s a symbol for those who stand vigil this way.

Preparing with hope for the future, coverlets for both table and bed.

Every petticoat, bonnet and linen was carefully folded away,

Then stored in a drawer or a camphor wood chest awaiting her wedding day.

There were cottons to wear in the summer. For winter some woolens were best.

As the hem of her apron was finished she put it away with the rest.

She learned how to sew by eleven and continued on throughout her life.

When love came to her she was twenty. She took vows as a coal miner’s wife.

The cabins that made up the village had slab sides and plain wooden floors,

A room with a table, a simple bed and fuel burning stove by the doors.

The wash tub stood out by the tank stand with the copper and stick leaning by.

The hem of her apron was sodden as she hung the wet clothes out to dry.

By noon on each Tuesday and Friday she had baked on her mother’s advice

Batches of biscuits and meat pies and fruit pies, bread that was crusty to slice.

Instead of the scraps of old fabric she had sewn to a thick padded square,

Sometimes she would use just a dish cloth to handle the hot pans with care.

Her baking would cool on the table then she’d wrap them and store them away.

The hem of her apron was crusty with the flour and grease from the tray.

Her usual habit was order and that Thursday she scrubbed the board floor.

She mopped and she dusted, moving the soot then sweeping it all out the door.

The force of the blast nearly floored her. First she felt it then she heard the sound.

Her instinct told her there was peril to the souls who were still underground.

Then she rose and in great trepidation she joined with the rest of the line.

The hem of her apron grew dusty from the road as she ran to the mine.

A full shift of men had been working at the time of that earth shaking blast.

Her husband had not made the surface. She would hold on with hope ‘til the last.

With each one they dragged from the rubble she would look and then sigh with relief

Over bodies of men who’d been robbed of life. This time coal was the thief.

She joined with a small band of others, and the priest, seeking comfort in Psalms.

The hem of her apron was crumpled as she crushed it between anxious palms.

Circumstance can make heroes of many. The humblest can often be brave.

From the darkness she saw stumbling figures helping others to walk from the cave.

All at once he broke through to the sunlight. The darkness had felt like a shroud.

Passing on his companion to others, he searched for her face in the crowd.

With a small cry of joy she ran forward and he stooped to receive her embrace.

The hem of her apron was blackened as she wiped dirt and tears from his face.

It was only three hours she waited in the dust and the crowd and the chill

And though he returned there were others who, remaining below them, were still.

That July in the mine at Mt Kembla, ninety six men were lost to coal.

We remember them still with a tribute, each one is a martyred soul.

Round the world there are millions of miners. Disaster can occur any day.

The hem of her apron’s a symbol for those who stand vigil this way.

inviata da Bernart - 23/7/2013 - 13:49

×

![]()

Versi di Zondrae Della Bona King

Musica di Raymond Crooke, musicista e folksinger australiano

Poesia vincitrice del Mount Kembla Mining Heritage Festival che annualmente si tiene in un villaggio sulle montagne del Nuovo Galles del Sud, nei pressi di Wollongong, che fu teatro di un grande disastro minerario quando il 31 luglio del 1902 una terribile esplosione in una miniera di carbone causò la morte di 96 minatori.