Ngomhla sibuyayo

Ngomhla sibuyayo, kophalal'igazi!

Ngomhla sibuyayo

Ngomhla sibuyayo

Ngomhla sibuyayo, kophalal'igazi!

Bakhala uVorster!

Bakhala uVorster!

Ngomhla sibuyayo, kophalal'igazi!

Ngomhla sibuyayo

Ngomhla sibuyayo

Ngomhla sibuyayo, kophalal'igazi! [1]

September '77

Port Elizabeth weather fine

It was business as usual

In police room 619

Oh Biko, Biko, because Biko

Yihla moja, yihla moja [2]

The man is dead

The man is dead

When I try to sleep at night

I can only dream in red

The outside world is black and white

With only one colour dead

Oh Biko, Biko, because Biko

Yihla moja, yihla moja

The man is dead

The man is dead

You can blow out a candle

But you can't blow out a fire

Once the flames begin to catch

The wind will blow it higher

Oh Biko, Biko, because Biko

Yihla moja, yihla moja

The man is dead

The man is dead

And the eyes of the world are

watching now

watching now.

Senzeni na? Senzeni na?

Senzeni na? Senzeni na?

Senzeni na? Senzeni na?

Senzeni na? Senzeni na?

Senzeni na? Senzeni na?

Senzeni na? Senzeni na?

Senzeni na? Senzeni na?

Senzeni na? Senzeni na? [3]

When we return

When we return

When we return, there'll be perfect silence!

When we return

When we return

When we return, there'll be perfect silence!

Vorster piangerà!

Vorster piangerà!

When we return, there'll be perfect silence!

When we return

When we return

When we return, there'll be perfect silence!

[2] From the chorus of the well known hymn of the African National Congress, Nkosi sikelel' iAfrika, originally written by Enoch Sontonga in 1897. The hymn is now South Africa's national anthem in a multilingual version (Zulu, Xhosa, English, Afrikaans). The Xhosa words mean: “Come down Holy Ghost”.

[3] From the anti-apartheid struggle song Senzeni na?, written around 1950. Senzeni na means: "What we have done?"

Contributed by Riccardo Venturi - 2005/4/8 - 18:36

BIKO

BIKOQuando torneremo

Quando torneremo, ci sarà silenzio perfetto!

Quando torneremo

Quando torneremo

Quando torneremo, ci sarà silenzio perfetto!

Vorster piangerà!

Vorster piangerà!

Quando torneremo, ci sarà silenzio perfetto!

Quando torneremo

Quando torneremo

Quando torneremo, ci sarà silenzio perfetto! [1]

Settembre '77

Port Elizabeth, tempo bello

Tutto procede come al solito

Nella stanza 619 del commissariato

Oh Biko, Biko, Biko, perché?

Discendi, Spirito Santo! [2]

Quest'uomo è morto

Quest'uomo è morto

Quando di notte provo a dormire

Riesco a sognare solo in rosso

Il mondo là fuori è bianco e nero

E l'unico colore è quello della morte

Oh Biko, Biko, Biko, perché?

Discendi, Spirito Santo!

Quest'uomo è morto

Quest'uomo è morto

Puoi spegnere una candela

Ma non puoi spegnere un incendio

Una volta che le fiamme hanno preso

Il vento le alimenterà

Oh Biko, Biko, Biko, perché?

Discendi, Spirito Santo!

Quest'uomo è morto

Quest'uomo è morto

E gli occhi del mondo ora

Stanno guardando

Stanno guardando.

Che cosa abbiamo fatto? Che cosa abbiamo fatto?

Che cosa abbiamo fatto? Che cosa abbiamo fatto?

Che cosa abbiamo fatto? Che cosa abbiamo fatto?

Che cosa abbiamo fatto? Che cosa abbiamo fatto?

Che cosa abbiamo fatto? Che cosa abbiamo fatto?

Che cosa abbiamo fatto? Che cosa abbiamo fatto?

Che cosa abbiamo fatto? Che cosa abbiamo fatto?

Che cosa abbiamo fatto? Che cosa abbiamo fatto? [3]

[2] Si veda Nkosi sikelel' iAfrika.

[3] Si veda Senzeni na?.

Contributed by Riccardo Venturi - 2019/8/21 - 21:05

Questa è una traduzione fatta da me.

Non sono sicuro che sia perfetta, ma mi sembra che ricalchi meglio il significato dell'ultima strofa...

(MarKco)

Settembre '77

A Port Elizabeth il tempo è bello

Tutto procede come al solito

nella stanza 619 del commissariato

Oh Biko, Biko, perché Biko

Oh Biko, Biko, perché Biko

Yihla Moja, Yihla Moja

Quest'uomo è morto

Quando di notte provo a dormire

riesco a sognare solo in rosso

Il mondo là fuori è bianco e nero

con un solo colore morto.

Oh Biko, Biko, perché Biko

Oh Biko, Biko, perché Biko

Yihla Moja, Yihla Moja

Quest'uomo è morto

Puoi soffiare su una candela

ma non puoi soffiare su un fuoco

Una volta che le fiamme hanno iniziato a bruciare

il vento le alimenterà

Oh Biko, Biko, perché Biko

Oh Biko, Biko, perché Biko

Yihla Moja, Yihla Moja

Quest'uomo è morto

E gli occhi del mondo ora

stanno guardando

stanno guardando

Contributed by MarKco - 2005/5/10 - 00:42

"Non è una traduzione alla lettera ma ho cercato di portare in italiano anche le sensazioni che il testo mi dava."

Settembre 1977

Port Elizabeth--tempo buono

tutto come al solito

stazione di polizia, stanza 619.

Biko, perché?

“Quest’uomo è morto”.

Quando cerco di dormire la notte

nei miei sogni un mare di rosso

Il mondo là fuori è un po’ bianco e un po’ nero,

ma un solo colore muore.

Certo, soffiando, puoi spegnere una candela,

ma così non puoi spegnere un incendio

Quando la fiamma comincia a bruciare

sarà proprio il vento a renderla indomabile.

Biko, perché?

“Quest’uomo è morto”.

Ma gli occhi del mondo

vi stanno guardando

ora.

Contributed by Irene - 2008/7/20 - 08:51

September '77

Port Elizabeth, schönes Wetter

Es war business as usual

Bei der Polizei im Raum 619

Oh, Biko, Biko, weil Biko

Oh, Biko, Biko, weil Biko

Yihla Moja, Yihla Moja - [1]

Der Mann ist tot

Wenn ich nachts zu schlafen versuche

Kann ich nur in Rot träumen

Die Welt da draußen ist schwarz-weiß

Wobei nur eine Farbe tot ist

Oh Biko, Biko, weil Biko, Biko

Oh Biko, Biko, weil Biko, Biko

Yihla Moja, Yihla Moja -

Der Mann ist tot

Man kann eine Kerze auspusten

Aber man kann niemals ein Feuer auspusten

Wenn die Flammen erst einmal anfangen, um sich zu greifen

Wird der Wind es noch höher wehen

Oh Biko, Biko, weil Biko, Biko

Oh Biko, Biko, weil Biko, Biko

Yihla Moja, Yihla Moja -

Der Mann ist tot, der Mann ist tot

Und die Welt

schaut zu

schaut zu [2]

[2] wörtlich: die Augen der Welt beobachten jetzt

Contributed by Riccardo Venturi - 2019/8/22 - 07:09

Versione tedesca degli ZAM [Zornige Alte Männer] / Schweinekombo

Version allemande du groupe ZAM [Zornige Alte Männer] / Schweinekombo

ZAM'in [Zornige Alte Männer] saksankielinen versio

"Stephen Bantu Biko war ein bekannter Bürgerrechtler in Südafrika. Er gilt als Begründer der Black-Consciousness-Bewegung. Am 11. September wurde Biko nackt und bewusstlos in einem Polizeiwagen mehr als 1000 Kilometer nach Pretoria transportiert. Dort starb er in der folgenden Nacht an seinen Verletzungen im Gefängniskrankenhaus. Am 13. September 1977 wurde sein Tod bekannt gegeben. Peter Gabriel setzte ihm in seinem dritten Studioalbum 1980 ein vielbeachtetes Denkmal." [ZAM]

September '77

Port Elizabeth - Sonnenschein

in sechs-eins-neun endlich Ruhe

nur ein Stuhl ging aus dem Leim

Oh Biko, Biko, because Biko

Oh Biko, Biko, because Biko

Jela Madja, jela Madja

- er ist tot, er ist tot.

Du löscht gerade noch eine Kerze

doch nicht ein großes Feuer

springt die Flamme einmal über

treibt der Wind sie immer höher

Oh Biko, Biko, because Biko

Oh Biko, Biko, because Biko

Jela Madja, jela Madja

- er ist tot, er ist tot.

Die lange Nacht ist viel zu heiß

ich träum nur noch in rot

Die Welt da draußen ist schwarz-weiß

nur eine Farbe tot

Oh Biko, Biko, because Biko

Oh Biko, Biko, because Biko

Jela Madja, jela Madja

- er ist tot, er ist tot.

Und alle, alle seh'n euch jetzt

seh'n euch jetzt seh'n euch jetzt

sie sind da

Contributed by Marcia - 2007/11/14 - 12:21

La versione basso-tedesca (dialetto di Colonia) di Wolfgang Niedecken (BAP, Da Capo, 1988)

Wolfgang Niedecken's Low German version (Köln dialect) (BAP, Da Capo, 1988)

Version bas-allemande (dialecte de Cologne) de Wolfgang Niedecken (BAP, Da Capo, 1988)

Wolfgang Niedeckenin alasaksankielinen versio (Kölnin murre) (BAP, Da Capo, 1988)

Bap live in St. Wendel 25. Juni 1989 Bosenbach Stadion

September sibbenunsibbzich,

Port Elizabeth, Südafrika.

Alles leef wie üblich aff -

Steven Biko litt em Graav.

Oh Biko, Biko, oh, Biko

Oh Biko, Biko, oh, Biko

Yihla Majo, Yihla Majo

Dä Mann ess duut,

Dä Mann ess duut.

Naahx, wenn ich schloofe will,

Dann träume ich nur en ruut.

Ahm Daach ess alles schwazz un wieß,

Steven Biko ess duut.

Oh Biko, Biko, oh, Biko

Oh Biko, Biko, oh, Biko

Yihla Majo, Yihla Majo

Dä Mann ess duut,

Dä Mann ess duut.

Kääzeflamme blööß mer uss,

Doch dat jeht nit met Füer.

Denn, wenn en Flamm eez eimohl griev,

Dann blööß jede Wind se nur hüher.

Oh Biko, Biko, oh, Biko

Oh Biko, Biko, oh, Biko

Yihla Majo, Yihla Majo

Dä Mann ess duut,

Dä Mann ess duut.

Un dä Rest vun der Welt,

Dä luhrt nur zo!

Dä luhrt nur zo!

Dä luhrt nur zo!

Contributed by Riccardo Venturi - 2019/8/22 - 05:52

Сентябрь 1977-го года,

Город Порт-Элизабет, погода отличная.

Это было обычное дело,

В полиции в камере 619.

О Бико, Бико, из-за Бико.

О Бико, Бико, из-за Бико.

Yihla Moja, Yihla Moja

- Этот мужчина умер.

Когда я пытаюсь спать по ночам,

Могу видеть сны только в красном цвете.

Внешний мир стал черно-белым

С единственным цветом - мертвым.

О Бико, Бико, из-за Бико.

О Бико, Бико, из-за Бико.

Yihla Moja, Yihla Moja

- Этот мужчина умер.

Можно задуть свечу,

Но нельзя задуть пожар.

Как только пламя займётся,

Ветер раздует его ещё выше.

О Бико, Бико, из-за Бико.

О Бико, Бико, из-за Бико.

Yihla Moja, Yihla Moja

- Этот мужчина умер.

И взоры всего мира

Смотрят сейчас,

Наблюдают сейчас.

Contributed by Riccardo Venturi - 2019/8/22 - 07:13

Wrzesień '77

Port Elizabeth pogoda w porządku

Były to interesy, jak zwykle

W pokoju policyjnym (numer) 619

Oh Biko, Biko, ponieważ Biko

Oh Biko, Biko, ponieważ Biko

Duchu przyjdź, Duchu przyjdź

- Człowiek nie żyje

Gdy próbuję w nocy spać

Mogę jedynie marzyć w czerwieni

Że świat na zewnątrz jest czarno-biały

Z tylko jednym kolorem martwym

Oh Biko, Biko, ponieważ Biko

Oh Biko, Biko, ponieważ Biko

Duchu przyjdź, Duchu przyjdź

- Człowiek nie żyje

Możesz zgasić świecę

Ale nie zgasisz ognia

Gdy już ogień zaczął płonąć

Wiatr będzie go unosił wyżej

Oh Biko, Biko, ponieważ Biko

Duchu przyjdź, Duchu przyjdź

- Człowiek nie żyje

A oczy świata

Patrzą teraz

Patrzą teraz...

Contributed by krzyś - 2013/12/21 - 06:16

Wrzesień 1977

Port Elizabeth, pogoda w porządku

Normalny bieg spraw

W policyjnym pokoju [nr] 619

Och Biko, Biko, bo Biko

Och Biko, Biko, bo Biko

Jihla Modża, Jihla Modża

- Mężczyzna zmarł

Kiedy próbuję spać w nocy

Potrafię tylko śnić w czerwieni

Zewnętrzny świat jest czarno-biały

A tylko jeden z [tych dwóch] kolorów jest martwy

Och Biko, Biko, bo Biko

Och Biko, Biko, bo Biko

Jihla Modża, Jihla Modża

- Mężczyzna zmarł

Możesz zdmuchnąć świecę

Ale nie możesz zdmuchnąć pożaru

Kiedy tylko płomienie się zaczepią

Wiatr go wzbije w górę swym podmuchem

Och Biko, Biko, bo Biko

Jihla Modża, Jihla Modża

- Mężczyzna zmarł

A oczy świata

Patrzą teraz

Patrzą teraz

Contributed by Riccardo Venturi - 2019/8/22 - 07:23

أيلول 1977

بور إيليزابيث, الجو على ما يرام

كانت الأعمال كما عادة

في الغرفة [رقم] 619 [في محطة] الشرطة

أوه بيكو, بيكو, بسبب بيكو

أوه بيكو, بيكو, بسبب بيكو

يهلا موجا, يهلا موجا

- قد مات [هذا] الرجل

عندما أحاول أن أنام في الليل

يمكنني فقط أن أحلم بالأحمر

العالم في الخارج هو أسود وأبيض

فقط أحد هذين اللونين ميت

أوه بيكو, بيكو, بسبب بيكو

أوه بيكو, بيكو, بسبب بيكو

ييهلا موجا, ييهلا موجا

- قد مات [هذا] الرجل

يمكنك أن تطفئ الشمعة بنفختك

ولكنك لا تستطيع أن تطفئ الحريق بنفختك

لما تبدأ الألهاب توقد

ستجعله الريح أعلى بهبه

أوه بيكو, بيكو, بسبب بيكو

يهلا موجا, يهلا موجا

- قد مات الرجل

وتنظر الآن

عيون العالم

تنظر الآن

Contributed by Riccardo Venturi - 2019/8/22 - 07:29

Renato Stecca - 2007/9/20 - 23:05

Non ha testo; ma, a volte, la musica esprime più delle "mere" parole. opinione opinabile e personale, ovviamente ;-)

cheers

Clivatxt [uno dei tanti Marco C.] - 2006/9/28 - 13:54

claudio - 2007/9/18 - 18:30

riesco a sognare solo in rosso

Il mondo là fuori è bianco e nero

con un solo colore morto.

la traduzione giusta è

IL MONDO LA FUORI E' BIANCO E NERO

LA MORTE E' DI UN COLORE SOLO

STEFANO - 2014/4/25 - 18:29

La rock band di Reggio Emilia si chiama Tokio ed ha realizzato questo video con un personalissimo arrangiamento di "Biko" con il quale verrà avviata una campagna di raccolta fondi a favore di un progetto di scambio culturale tra giovani musicisti Reggiani e Sudafricani.

Ecco il video:

Paolo Genta - 2014/6/28 - 15:04

fabrizio - 2014/8/6 - 03:22

Flavio Poltronieri

Flavio Poltronieri - 2020/3/9 - 10:32

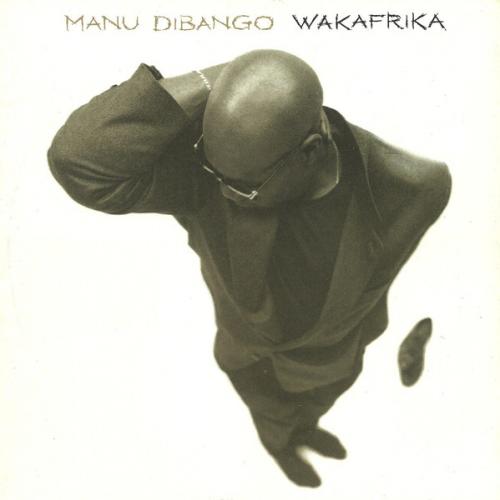

Due settimane fa avrebbe dovuto partecipare ad un concerto per celebrare i sessant’anni dell’indipendenza del Benin dalla Francia. Purtroppo martedi scorso, anche il sassofonista camerunense è stato ucciso dal covid 19, a Parigi.

Flavio Poltronieri - 2020/3/27 - 08:17

La copertina di "Wakafrika" è davvero una delle più originali e belle che io abbia mai visto...

E Soul Makossa è sempre stato uno dei miei brani preferiti... l'aveva riproposto anche in "Wakafrika", 20 anni dopo.

Saluti

B.B. - 2020/3/27 - 18:11

Lorenzo - 2020/3/27 - 18:31

Note for non-Italian users: Sorry, though the interface of this website is translated into English, most commentaries and biographies are in Italian and/or in other languages like French, German, Spanish, Russian etc.

Lyrics and music / Testo e musica / Paroles et musique / Sanat ja sävel: Peter Gabriel

Single release: 1980

Album release: Peter Gabriel III [1980]

Also performed and recorded by / Altri interpreti / Autres interprètes / Laulun muut tulkit:

Robert Wyatt (1984) in "Work in Progress"

Joan Baez (1987) in "Recently".

BAP (1988)

Cudù (1988) in "Vivo"

Simple Minds (1989) "Street Fighting Years".

Manu Dibango (1994) in "Wakafrika".

Playing for Change in "Songs Around the World".

Paul Simon (2010) in "And I'll Scratch Yours".

Nomadi e poi Danilo Sacco dal vivo

(dq82)

Steve Biko era il leader pacifista e antirazzista del partito comunista sudafricano (all'epoca fuorilegge), ucciso dalla polizia del regime dell'Apartheid nel 1977.

Probabilmente una delle più famose e belle canzoni di Peter Gabriel. [RV-2005]

The song is a musical eulogy, inspired by the death of the black South African anti-apartheid activist Steve Biko in police custody on 12 September 1977. Gabriel wrote the song after hearing of Biko's death on the news. Influenced by Gabriel's growing interest in African musical styles, the song carried a sparse two-tone beat played on Brazilian drum and vocal percussion, in addition to a distorted guitar, and a synthesised bagpipe sound. The lyrics, which included phrases in Xhosa, describe Biko's death and the violence under the apartheid government. The song is book-ended with recordings of songs sung at Biko's funeral: the album version begins with "Ngomhla sibuyayo" and ends with "Senzeni Na?", while the single versions end with "Nkosi Sikelel' iAfrika".

"Biko" reached No. 38 on the British charts, and was positively received, with critics praising the instrumentation, the lyrics, and Gabriel's vocals. A 2013 commentary called it a "hauntingly powerful" song, while review website AllMusic described it as a "stunning achievement for its time". It was banned in South Africa, where the government saw it as a threat to security. "Biko" was a personal landmark for Gabriel, becoming one of his most popular songs and sparking his involvement in human rights activism. It also had a huge political impact, and along with other contemporary music critical of apartheid, is credited with making resistance to apartheid part of western popular culture. It inspired musical projects such as Sun City, and has been called "arguably the most significant non-South African anti-apartheid protest song".

Bantu Stephen Biko was an anti-apartheid activist who was a founding member of the South African Students' Organisation in 1968 and the Black People's Convention in 1972. Through these groups, and through other activities, he promoted the ideas of the Black Consciousness movement, and became a prominent member of the resistance to apartheid in the 1970s. The government of South Africa placed a banning order on him in 1973, preventing him from leaving his hometown, meeting with more than one person, publishing his writing, and speaking in public. In August 1977 Biko was arrested for breaking his banning order.

After his arrest Biko was held in custody in Port Elizabeth, Eastern Cape for several days, during which he was interrogated. During his interrogation he was severely beaten by some of the policemen questioning him. He suffered severe injuries, including to his brain, and died soon after on 12 September 1977. News of his death spread quickly, and became a symbol of the abuses perpetrated under the apartheid government. Biko's position as an individual who had never been convicted of a crime led to the death being reported in the international press; he thus became one of first anti-apartheid activists widely known internationally.

Several musicians wrote songs about Biko, including Tom Paxton, Peter Hammill, Steel Pulse, and Tappa Zukie. British musician Peter Gabriel, who heard of Biko's death through the BBC's coverage of the event, was moved by the story and began researching his life, based on which he wrote a song about the killing. This coincided with Gabriel becoming interested in African musical styles, which influenced his third solo album Peter Gabriel (1980), also known as Melt, on which "Biko" was ultimately included. Gabriel was also influenced to write the song through his association with politically inclined new-wave musician Tom Robinson; Robinson is said to have encouraged Gabriel to release the piece when Gabriel began to have doubts. Though there were other political songs on the album, "Biko" was the only piece that was explicitly a protest song.

The lyrics of the song begin in a manner similar to a news story, saying "September '77/Port Elizabeth, weather fine". The next lines mention "police room 619", the room in the police station of Port Elizabeth in which Biko was beaten. The English lyrics are broken up by the Xhosa phrase "Yila Moja" (also transliterated "Yihla Moya") meaning "Come Spirit": the phrase has been read as a call to Biko's spirit to join the resistance movement, and as a suggestion that though Biko was dead, his spirit was still alive.

The tone of the songs shifts after the first verse, growing more defiant, and the second verse of the song criticises the violence under apartheid, with Gabriel singing about trying to sleep but being able to "only dream in red" because of his anger at the death of black people. The lyrics of the third verse seek to motivate the listener: "You can blow out a candle/But you can't blow out a fire/Once the flames begin to catch/The wind will blow it higher", suggesting that though Biko is dead, the movement against apartheid would continue. The lyrics express a sense of outrage, not only at the suffering of people under apartheid, but at the fact that that suffering was often forgotten or denied.

Gabriel incorporated three songs by other composers into his recording. The album version of the songs start with an excerpt from the South African song "Ngomhla sibuyayo" and ends with a recording of the South African song "Senzeni Na?", as sung at Biko’s funeral. The 7- and 12-inch single versions ended instead with an excerpt from "Nkosi Sikelel iAfrika", a song which would later become South Africa's National Anthem. The German version of the song began and ended with "Nkosi Sikelel iAfrika". The recording ends with a double drum beat reminiscent of gun shots that cuts off the singers at the funeral, seen as representing a repressive government.

The recording at the beginning of the song fades into a two-toned percussion, played on a Brazilian Surdo drum, described by Gabriel as the "spine of the piece". "Biko" makes use of a "hypnotic" drum beat throughout the song, influenced strongly by African rhythms Gabriel had heard. In particular, Gabriel would credit the soundtrack LP Dingaka with influencing the percussion of the track. Music scholar Michael Drewett writes that Gabriel tried to create an "exotic" African beat "without really approximating the sound he imitated", thus creating a "pseudo-African" beat. The tune is punctuated with vocal percussive sounds that have a "primordial" feeling, combining Gaelic and African influences. The drums are overlaid with an artificially distorted two-chord guitar sound, which fades out briefly during the vocal percussion, before returning during the first verse.

The first verse describing Biko's death is followed by a distinct chord change before the Xhosa invocation "Yihla Moya". The sound of bagpipes, created with a synthesiser, enters the song during the interlude between the verses. Played in a "mournful" minor key, they have been variously described as creating a "funeral" and a "militaristic" atmosphere. The bagpipes continue alongside the drums and guitar through the second verse, followed by an interlude identical to the first. A snare drum is also added to the sound for the second and third verses. The third verse concludes with a non-verbal chant following the chord progression of the song, while the climax is a chorus of male voices, accompanied by bagpipes and drums.

Gabriel provided lead vocals and piano. The guitarist for "Biko" was David Rhodes, Gabriel's longtime collaborator. Other participants included Jerry Marotta on drums, Phil Collins on surdo, Larry Fast on synths and synthesised bagpipes, and Dave Ferguson on screeches. However, a 2016 "listener's companion" to Gabriel's music named Phil Collins as the drummer on the song, Larry Fast as playing the synthesiser, and Jerry Marotta as playing the snare drum.

"Biko" was first released as a single in 1980. Gabriel donated the proceeds from both versions of the single to the Black Consciousness Movement in South Africa. These donations would total more than 50,000 pounds. The B-side of the 7" version contained Gabriel's version of the Ndebele folks song "Shosholoza", while the 12" version also carried a German vocal version of Gabriel's 1979 track "Here Comes the Flood".

"Biko" was included on Gabriel's third solo album Peter Gabriel III (1980) (a.k.a. Melt) released by Charisma Records in 1980. At seven and one-half minutes, it was the album's longest song. The track was later included on his 1990 compilation Shaking the Tree: Sixteen Golden Greats.

Upon its release "Biko" reached No. 38 on the British chart. The 1987 live version reached No. 49 in the UK. In 2016 Gabriel's biographer Durrell Bowman ranked "Biko" as among Gabriel's 11 most popular songs. Peter Gabriel III topped the British charts for two weeks, giving Gabriel his first No. 1 hit.

Soon after its release, a copy of "Biko" was seized by South African customs and submitted to the Directorate of Publications, which banned the song and the album on which it featured for being critical of apartheid, calling it "harmful to the security of the State". Thus, despite enduring popularity outside South Africa, it had no presence within the country.

The song received strongly positive responses from critics, and it was frequently cited as the highlight of the album. Phil Sutcliffe in Sounds magazine said the song was "so honest you might even risk calling it truth". Music website AllMusic called "Biko" a "stunning achievement for its time", and went on to say that "It's odd that such a bleak song can sound so freeing and liberating". Writing in 2013, Mark Pedelty would say that "Biko" "stood out for its unusual instrumentation (bagpipes and synthesiser), haunting vocals, and funerary chant," and credited Gabriel with doing a "masterful job of creating catalytic imagery and getting out of the way". Music scholar Michael Drewett wrote that the lyrics skillfully engaged the listener by moving from a specific story to a call for action.

The musical elements of the song also received praise. Drewett stated that Gabriel's singing throughout the song was "clear and powerful". Though Drewett questioned the use of bagpipes, he stated that they heightened the emotional effect of the song. 2013, scholar Ingrid Byerly called "Biko" a "hauntingly powerful" song, with "a hypnotic drumbeat thundering beneath commanding guitar, lyrical bagpipe dirges, and the intense eulogy of Gabriel's voice". A review in Rolling Stone was more critical of the song, saying that the melody and rhythms of the piece were "irresistible", but that the song was a "muddle", and that "what Gabriel [had] to say was mostly sentimental."

Gabriel's use of Xhosa lyrics have been read by scholars as evidence of the "authenticity" of Gabriel's effort to highlight Biko. By using a language that many South Africans, and the majority of outsiders, did not know, the words trigger curiosity; in the words of Byerly, "compelling [listeners]...to become, like Gabriel, insiders to the struggle". In contrast, scholar Derek Hook has written that the song highlighted the artist, rather than Biko himself, and "[secured] for the singer and his audience a kind of anti-racist social capital". Hook questioned whether the "consciousness raising" efforts of the song could turn into "anti-racist narcissism". Drewett stated that the use of a simplistic and generic "African" beat was an indication of an "imperial imagination" in the song's composition.

"Biko" had an enormous political impact. It has been credited with creating a "political awakening" both in terms of awareness of the brutalities of apartheid, and of Steve Biko as a person. It greatly raised Biko's profile, making his name known to millions of people who had not previously heard of him, and came to symbolise Biko in the popular imagination. Byerly writes that it was an example of the "right song written at the right time by the right person"; it was released in circumstances of social tension that contributed to its popularity and influence. It triggered a rise in enthusiasm for fighting against apartheid internationally, and has been described as "arguably the most significant non-South African anti-apartheid protest song".

"Biko" was at the forefront of a stream of anti-apartheid music in the 1980s, and sparked a worldwide interest in music exploring the politics and society of South Africa. Along with songs such as "Free Nelson Mandela" by The Specials, and "Sun City" by Artists United Against Apartheid, "Biko" has been described as part of the "soundtrack for the global divestment movement", which sought to persuade divestment from companies doing business in apartheid South Africa. These songs have been described as making the fight against apartheid part of Western popular culture. Gabriel's piece has been credited as the inspiration for many of the anti-apartheid songs that followed it. Steven Van Zandt, the driving force behind the 1985 track "Sun City" and the Artists United Against Apartheid initiative, stated that hearing "Biko" inspired him to begin those projects; on the cover of the album, he thanked Gabriel "for the profound inspiration of his song ‘Biko’ which is where my journey to Africa began". Irish singer and U2 frontman Bono called Gabriel to tell him that U2 had learned of the effects of apartheid from "Biko".

The song was a landmark for Gabriel's career. "Biko" has been called Gabriel's first political song, his "most enduring political tune", and "Arguably [his] first masterpiece". It caught the attention of activist organisations, and in particular anti-apartheid groups and human rights organisations such as Amnesty International (AI). "Biko" became popular among AI workers, along with Gabriel's 1982 song "Wallflower". The song triggered Gabriel's involvement in musical efforts against apartheid: he supported the "Sun City" project, and participated in two musical tours organised by AI: A Conspiracy of Hope in 1986, and Human Rights Now! in 1988. It also led to him beginning a deeper involvement in those groups.

Gabriel sang the piece at Nelson Mandela 70th Birthday Tribute concert at Wembley Stadium in 1988. The concert featured a number of well-known artists, including Dire Straits, Miriam Makeba, Simple Minds, Eurythmics, and Tracy Chapman. During his live performances of "Biko", Gabriel frequently concluded asking the audience to engage in political action, saying "I've done what I can, the rest is up to you." It was often the last song of a performance, with the band members gradually leaving the stage during the song's concluding drum coda.

A live version, recorded in July 1987 at the Blossom Music Center in Cuyahoga Falls, Ohio, was released as a single later that year, to promote Richard Attenborough's Biko biopic Cry Freedom. The music video consists of clips from the film and Gabriel singing. The song did not appear in the actual film.

"Biko" was covered by a number of well known artists. Robert Wyatt's 1984 version from his Work in Progress EP made #35 in that year's John Peel Festive Fifty. "Biko" was featured prominently in "Evan", the penultimate episode of the first season of the American television show Miami Vice in 1985. Folk musicians and activist Joan Baez recorded a version on her 1987 album Recently. Simple Minds released a cover version on their 1989 album Street Fighting Years, a version later featured on other collections of their music. It was covered by Cameroonian musician Manu Dibango on his 1994 album Wakafrika. Dibango's version also featured Gabriel, Sinead O'Connor, Ladysmith Black Mambazo, Geoffrey Oryema, and Alex Brown. Folk-rock musician Paul Simon recorded a cover of the song for inclusion on the 2013 Gabriel tribute album And I'll Scratch Yours.

en.wikipedia : Biko (song)

(Antonio Piccolo)

di Pier Maria Mazzola

Quell’uomo dall’animo così musicale si chiamava Gideon Nieuwoudt. Fu lui, con altri aguzzini, a “interrogare” Steve Biko, agli arresti da venti giorni, il 6 settembre 1977 nella stanza 619 del comando di polizia di Walmer, Port Elizabeth. Biko ne uscì irrimediabilmente malconcio. Per gli agenti, era stato un «incidente »: il prigioniero si agitava troppo… era andato a sbattere con la testa contro il muro. Praticamente di sua iniziativa.

Né amnistia né condanna

Nel 1997, vent’anni dopo la sua morte per «sciopero della fame», Gideon Nieuwoudt ed altri quattro sgherri hanno ammesso, davanti alla Commissione Verità e Riconciliazione presieduta da Desmond Tutu, qualche responsabilità, anche in molti altri casi oltre a questo.

A proposito: non pago dell’impresa, nel 1987 il colonnello Nieuwoudt si era dedicato anche ad appiccare il fuoco alle sale dove era in cartellone Grido di libertà, il film su Biko. Ma non hanno ottenuto l’agognata amnistia, non essendo stati esaustivi sulle circostanze della tortura-omicidio.

Va anche aggiunto che, nel 2003, la giustizia sudafricana li ha poi prosciolti per insufficienza di prove. Se fossa ancora vivo, oggi avrebbe meno di 60 anni. Quando venne massacrato dal regime segregazionista sudafricano era appena trentenne. Il nostro ricordo di Steve Biko, il giovane ribelle della Coscienza Nera.

E di altri due grandi protagonisti della lotta contro l’apartheid maginare come ci siano rimasti i figli di Steve, Nkosinathi e Samora, e la vedova Ntsiki che a suo tempo si era rivolta alla Corte Costituzionale per impedire che gli assassini del marito beneficiassero della Commissione Verità e Riconciliazione.

Ma che cos’aveva di tanto temibile un giovane uomo come lui, da indurre il regime di Pretoria dapprima a metterlo al bando, in condizioni di semi-isolamento, e poi a finirlo con la ferocia che sappiamo?

Pedagogia degli oppressi

Il suo primo impegno fu con l’Unione nazionale degli studenti sudafricani (Nusas). Ma nel 1969 se ne staccò per fondare l’Organizzazione degli studenti sudafricani (Saso). Nella Nusas militavano anche giovani bianchi, la loro presenza era preponderante, Biko si convinse presto della necessità di uno spazio dove i neri in quanto tali si valorizzassero in modo autonomo. Prendeva corpo la Black Consciousness: la “Coscienza (o Consapevolezza) nera”.

Il giovane Steve aveva annusato lo spirito del tempo, soprattutto quello che soffiava sull’Africa (la negritudine, Kwame Nhrumah, Amílcar Cabral…), sugli Stati Uniti (Malcolm X, il Black Power e la Black Theology…), sull’America Latina (Paulo Freire e la sua pedagogia degli oppressi). «Per “Coscienza nera” - spiegava Biko - io intendo la rinascita politica e culturale di un popolo oppresso. Ora i neri in Africa sanno che i bianchi non saranno conquistatori per sempre.

Questa scoperta li conduce a porsi la domanda: “Chi sono io? Chi siamo?”. La sfida della decolonizzazione è stata condivisa dai bianchi liberali. Per qualche tempo si sono comportati come portavoce dei neri. Ma poi qualcuno di noi ha cominciato a chiedersi: “Possono forse i nostri amici liberali mettersi al posto nostro?”. La nostra risposta fu: “No!... Finché i bianchi liberali sono i nostri portavoce, non ci sarà nessun portavoce nero”».

Bianco, ma amico

Da qui all’accusa di razzismo (alla rovescia), il passo era breve. Ma Biko non si lasciò spiazzare: «Ancora oggi - confessava nell’anno della sua morte - noi siamo accusati di razzismo. È un errore. Noi sappiamo che tutti i gruppi interrazziali in Sudafrica hanno rapporti nei quali i bianchi sono superiori, i neri inferiori.

Così, per cominciare, i bianchi devono rendersi conto di essere solamente “umani”, non superiori. La stessa cosa per i neri, che devono rendersi conto di essere umani, non inferiori. Per tutti noi questo significa che il Sudafrica non è europeo, ma africano».

Grido di libertà è un film che il regista Richard Attenborough (quello di Gandhi) ha costruito proprio sull’amicizia di Biko (la prima interpretazione importante di Denzel Washington) con un giornalista, un bianco liberale.

È grazie a lui, del resto, che sappiamo molte cose di Biko, affidate a un libro di memorie. Per Donald Woods (questo il suo nome), che pagò con l’esilio il suo rapporto con Biko, «l’amico che più apprezzavo era un uomo speciale, straordinario. Nei tre anni che lo conobbi, non ebbi mai il minimo dubbio che fosse il leader più importante dell’intero paese.

Era saggio, pieno di humour, compassionevole, brillante, altruista, modesto, coraggioso. Il governo non ha mai capito quanto Biko fosse uomo di pace. Il suo costante obiettivo era la riconciliazione pacifica di tutto il Sudafrica».

Dopo Soweto

Nel 1972 Steve Biko è tra i fondatori della Black Peoples Convention, federazione di una settantina di gruppi che si riconoscono nella filosofia della coscienza nera. In questo ambiente si prepararono le manifestazioni di protesta di Soweto, la township di Johannesburg teatro, il 16 giugno 1976, di una durissima repressione della polizia.

Quel giorno vennero massacrati almeno cento neri. La rivolta dilagò per il paese e in un anno si contarono un migliaio di vittime. Moltissimi i giovani, anche bambini. Non era difficile, per il regime, collegare il nome di Biko alla rinnovata consapevolezza che sosteneva la gioventù nella lotta contro l’apartheid.

Biko non fece mai parte dell’African National Congress (Anc), il movimento storico - quello di Nelson Mandela - che dal 1912 convogliava l’ansia di riscatto della maggioranza nera. Per il leader studentesco, l’Anc era in un certo senso troppo “moderato”, anche se aveva poi fatto la scelta, non condivisibile per un nonviolento come Biko, di costituire un braccio armato.

Ma prima del suo arresto definitivo, Biko stava preparandosi, come ricorda lo stesso Mandela, a un incontro segreto con Oliver Tambo, il successore di Lutuli alla presidenza dell’Anc. Di quella nascente alleanza il governo aveva sicuramente paura.

Forse, anche per questo Biko venne ammazzato.

Ammazzato? «Biko vive!», gridano ancora i graffiti dai muri delle periferie sudafricane.